Introduction: The World Wars

(1914-1918; 1939-1945)

The Jews of Poland were not strangers to the winds of war. Poland had long been a land torn by the power struggles of the empires to its east and west. In the First World War (1914-1918), which was triggered by the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo, the Central Powers of Austria-Hungary, Germany, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire waged war against Imperial Russia, France, Great Britain, and the United States. During the war, the Jews who lived in Poland experienced life under occupation, with borders shifting between Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary over the course of the war. When World War I came to an end, Poland was finally reconstituted as an independent state. To the west, however, many in Germany were unsettled by the defeat in the war. The German desire for expansion would express itself within two decades in a new war - World War II, 1939-1945 - which would once again envelop the Jews as victims caught in the cross-fire; moreover, this time the war would directly target the Jews. Adolf Hitler had promised that the next world war would be one of Jewish annihilation. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, three million Jews came under Nazi rule; in June 1941, Germany invaded the USSR and the Nazi fire surrounded another two million Jews.

The Destruction of European Jewry

{{table}}

Polish Jews under Nazi Rule

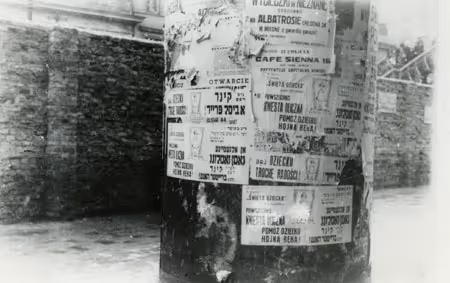

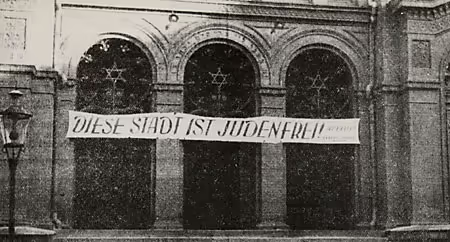

The Jewish residents of Germany had been stripped of their basic human rights following the Nazi rise to power in 1933. First subject to humiliation and progressive exclusion from German economic, political, and cultural life, the Jews became pariahs in German society. Once the Nazis occupied western Poland in September 1939, Polish Jewish citizens there were marked for special persecution. They suffered a complete loss of their civil rights, which included being limited in the physical space they could inhabit. Beginning in November 1939, in the Nazi-occupied provinces of Poland, Jews were required to wear a yellow badge to identify them as Jews. Jewish males were conscripted for forced labor and any assets possessed by Jews were expropriated by the German authorities.

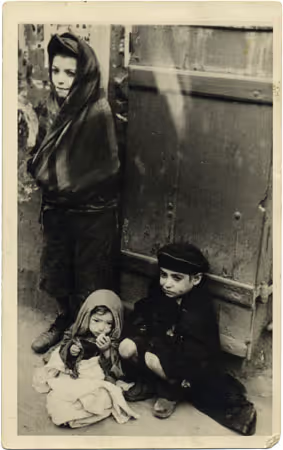

Over the course of 1940 and 1941, Jews in virtually all major Polish cities were herded into urban ghettos, which were sealed off from the surrounding population. The ghetto streets, wired and enclosed, were cramped with massive number of displaced families. They became scenes of mass death, as the impoverished Jewish population slowly died from malnourishment and disease. In June 1941, as Germany invaded the USSR, mobile killing squads called Einsatzgruppen, which followed the invading Wehrmacht (German army), began the systematic extermination of Jews in eastern Poland and the western Russian provinces. At some point in 1941, the Nazi regime decided to expedite the process of Jewish extermination by employing more "efficient" methods of mass killing through special extermination camps, among which were Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Treblinka, Sobibor, and Auschwitz. By the end of the World War II, three million Polish Jews (92% of the pre-war population) would be murdered.

Jewish Life in Nazi Ghettoes

In the first year following the Nazi invasion of Poland, much of the Jewish population was confined in large urban ghettos. The Warsaw ghetto, established in October 1940, was sealed from the outside world in November 1940. Eventually close to 450,000 Jews would be crowded into this largest ghetto in Poland; just over 30% of the overall population of Warsaw was packed into 2% of the total area of the city. Jews were forced to live six and seven to a room, with a total lack of sanitary facilities to accommodate the newly crowded conditions. Most alarming, however, was the ghetto food supply. The Judenrat, (the Jewish administration responsible for all realms of Jewish life within the ghetto), headed by Adam Czerniakow, who later committed suicide, was only able to purchase what amounted to miniscule rations for the Jews in the ghetto. Within the first 18 months after the establishment of the Warsaw ghetto, 20% of the population had died due to starvation and the terrible sanitary conditions.

Nonetheless, the Jews who were forced to live within the walls of the ghetto in Warsaw and in other cities did just that: they struggled valiantly to survive using all the ways they could. Jewish children in the ghetto were still educated, with small groups of children being taught in secret by a teacher whose salary usually consisted of a little food. Zionist youth movements in the Warsaw ghetto also operated two underground high schools. In the Lodz ghetto, where education was permitted, 14,000 students attended 2 kindergartens, 34 secular schools, 6 religious schools, 2 high schools, 2 college-level schools, and one trade school in the period between 1940-1941. One 15-year-old boy in Vilna, Yitzhak Rudashevsky, aged 15, described the importance of having some diversion during the long days in the ghetto:

"My mood is just like the weather outside. I think to myself: what would happen if we did not go to school, to the club, and did not read books? We would die of dejection inside the ghetto walls."

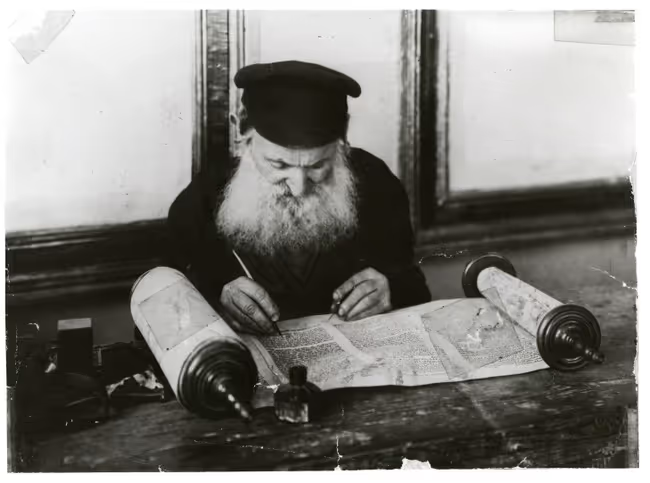

Despite the hardships inherent in ghetto life, religious Jews continued their observance. The historian of the Warsaw ghetto, Emmanuel Ringelblum, estimated that some 600 minyanim regularly met to hold prayer services within the walls of the ghetto. Additional prayers were added to services, with special prayers recited for deliverance, such as Psalms 22 and 23, as well as prayers composed during the persecutions of the Crusades and the Middle Ages, which recalled those who chose martyrdom rather than denying the Jewish faith. Observing religious commandments, such as the keeping of the Sabbath and dietary laws (Kashrus), became nearly impossible in the ghettos. Jews were forced to work on the Sabbath and holy days; rabbis made special exceptions to permit the consumption of non-kosher food, declaring that the preservation of life for those who were starving was more important than observing religious commandments. In the Kovno ghetto, the young Rabbi Ephraim Oshry attempted to address the new moral and ethical dilemmas of life under Nazi rule, providing answers based on halakhah to such unimaginable questions as whether a Jew was allowed to accept a work permit with the knowledge that it would lead to the death of another Jew, or whether it was permissible for a Jew to acquire a forged birth certificate that hid his/her Jewish identity.

Social welfare organizations functioned in the ghettos, trying desperately to prevent the death from starvation and disease of the neediest Jews. In the Warsaw ghetto over 1,000 "house committees" were organized to provide education for small children and to encourage self-help among the inhabitants of individual apartment buildings. The committees also organized cultural activities for the inhabitants of the buildings and were themselves part of the umbrella group Zetos (The Jewish Association for Mutual Aid), and prior to December 1941, the Warsaw branch of the American Joint Distribution-AJD (AJDC) headed by the historian, Emmanuel Ringelblum. These welfare organizations also ran soup kitchens, as well as ghetto hospitals, schools for nurses, and a system of orphanages. The great Jewish educator, Janusz Korczak, who was also a physician, writer, and pedagogue, became head of the Warsaw Jewish Orphanage. In the ghetto, he did everything within his power to improve the situation of the children in his orphanage. Although offered the chance, he rejected the opportunity of going into hiding outside the ghetto and instead chose to stand by his orphans. On August 5, 1942, Korczak and the 200 children in his orphanage were deported to the Treblinka death camp where they all perished.

.avif)

.avif)