Lublin

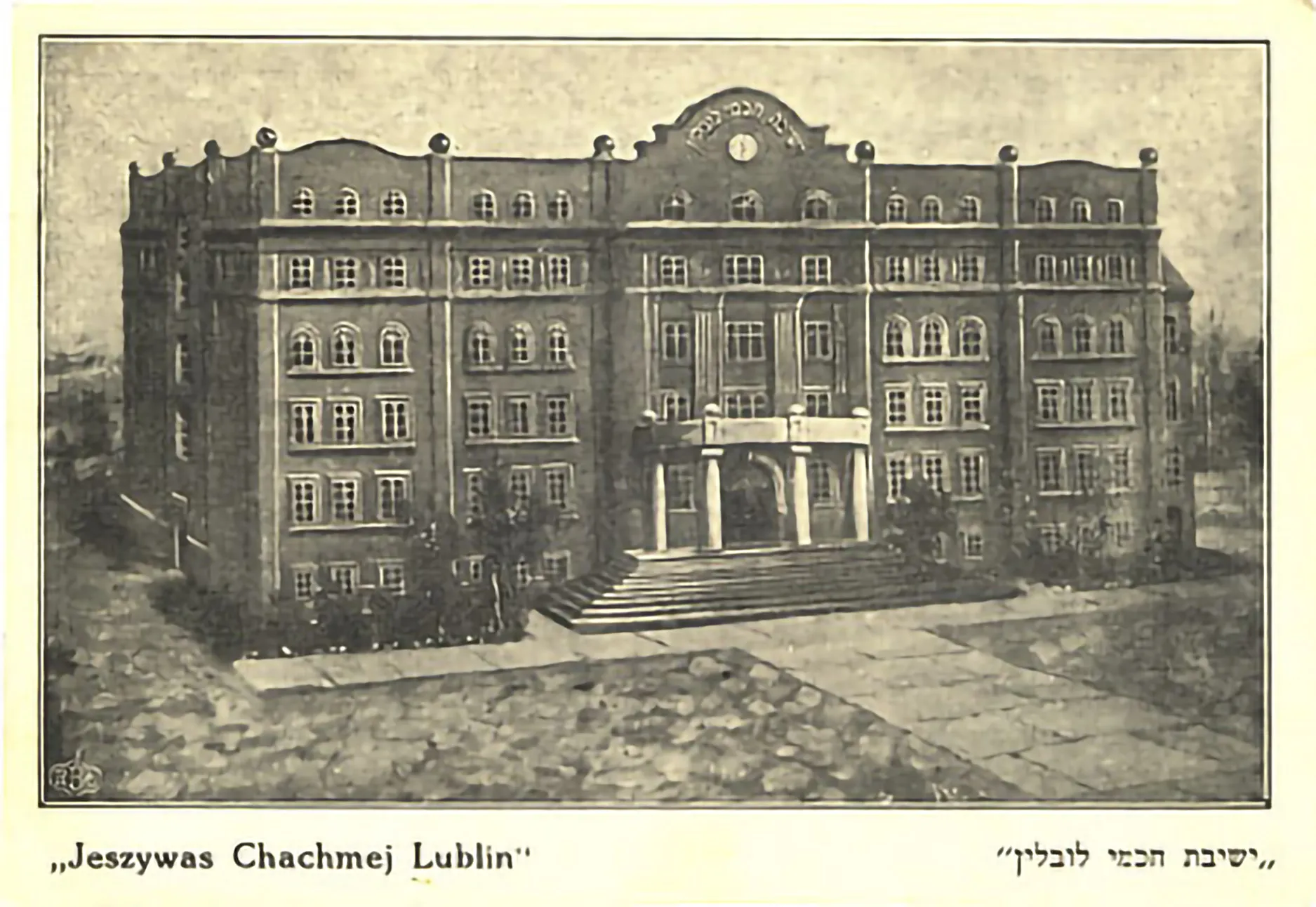

The building of Yeshivas Khakhmey Lublin. Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe, sygn.

Yeshivas Khakhmey Lublin has enjoyed a somewhat legendary status. Its founder, Meir Shapira (1887-1933), dreamed of creating a cutting-edge yeshiva that would provide young Torah scholars with a perfect study environment

History and Settlement

Though a small and secondary city today, Lublin was once a great center of Polish Jewry and functioned for a time as the industrial capital of Poland. Its rich history belies its current size and character. The variety within its former Jewish community provides a microcosm of Polish-Jewish culture during the last centuries.

Founded during the 9th century as a fortified royal outpost situated along the busy trade routes of eastern Poland, Lublin's centrality made it a hub for provincial and foreign traders, who arrived at its renowned market days with an impressive variety of goods, including produce, spices, silk, horses, oxen, fur, leather, iron, steel, and wagons. As Lublin grew into a proper town, its teeming streets were distinguished by the variety of

products and trade: tailors, furriers, brewers, bakers, artisans, shoemakers, grocers. As elsewhere, Jewish merchants and artisans were bitterly opposed by Polish guilds that rivalry continued until 1805, when the two groups joined together into unified guilds. In addition to being a royal city and an economic hub, Lublin was once also the center of Jewish self-government in Poland - the seat of the Council -(Council of four lands)(Va'ad d'arba Artzot in Hebrew) - the Jewish bureaucracy charged with overseeing all of the kehillot of Poland's Jewish communities.

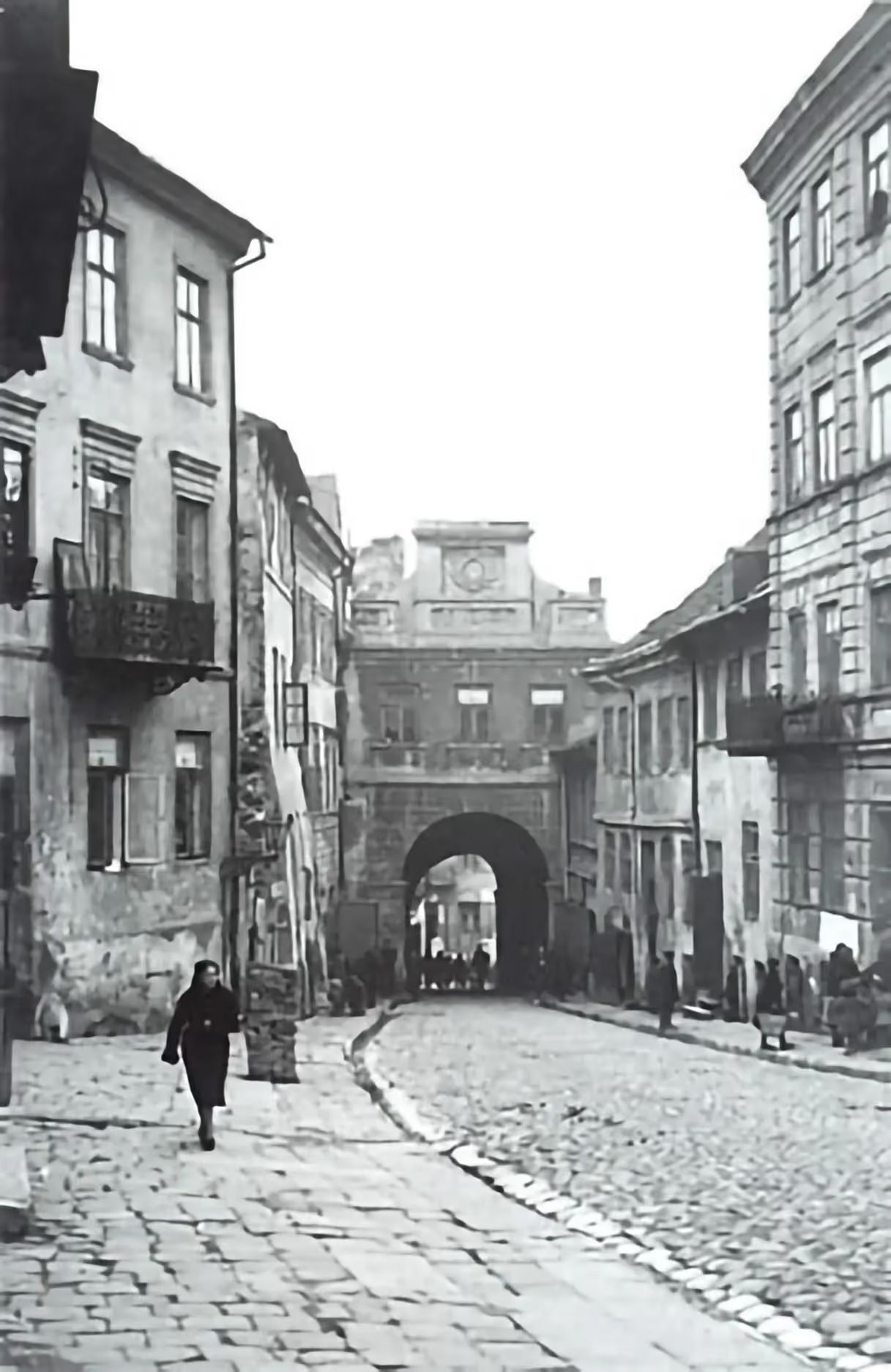

Jews had first arrived in Lublin during the 14th century in response to an official invitation from King Casimir (Kazmierz), who sought the economic experience and ideas of Germans and Jews for his emerging stronghold. As in other cities, the Jews of Lublin were restricted to living in specific areas outside of the original city called Piaski Zydowskie (Jewish Sands). In the 16th century, Jews were allowed to settle at the foot of the castle and they established the new Jewish quarter called Podzamcze. Lublin's core Jewish community flowered in Podzamcze, and was initially focused around Szeroka Street (Broad Street), with its diverse array of institutions, offices, and synagogues. In modern times, the main thoroughfare became Lubartovska Street, a busy boulevard of Jewish shops both large and small. At the time of World War II, Podzamcze's "Jewish City" within the city had been developing for almost 400 years and it still was the heart of the community for Lublin's 400,000 Jews (just under one-third of the city's population).

Institutions

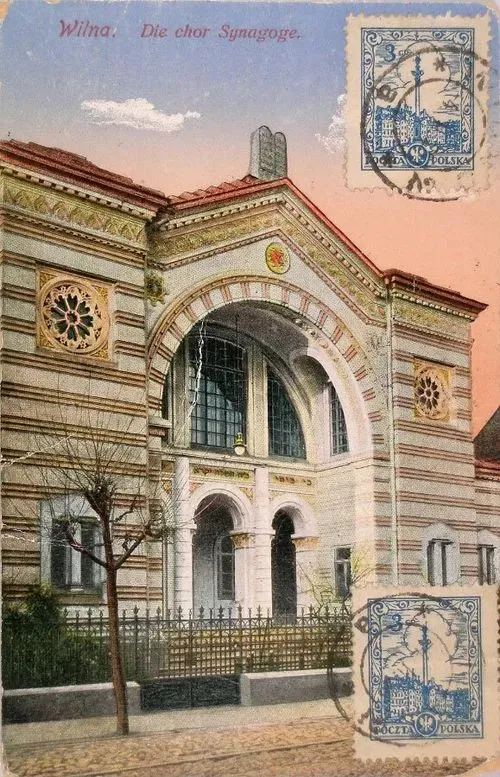

A look at Lublin's physical institutions during the years between the two World Wars (1919-1939) would have revealed at least 11 synagogues, the greatest of which - the Maharshal Shul - was an important architectural landmark and a gem among Jewish buildings. Constructed in 1567 in honor of Rabbi Shlomo ben Yekhiel Luria (aka "Maharshal"), the Maharshal Shul was the stone and brick embodiment of the Lublin Jewish community's growing wealth and desire for permanence. The building destroyed by fire and rebuilt in the 17th century, actually consisted of two synagogues. Together they seated 3,000 worshippers. The synagogue was destroyed by Nazi aerial bombardment in September 1939 - today only a few etchings of its interior remain to remind us of its magnificence.

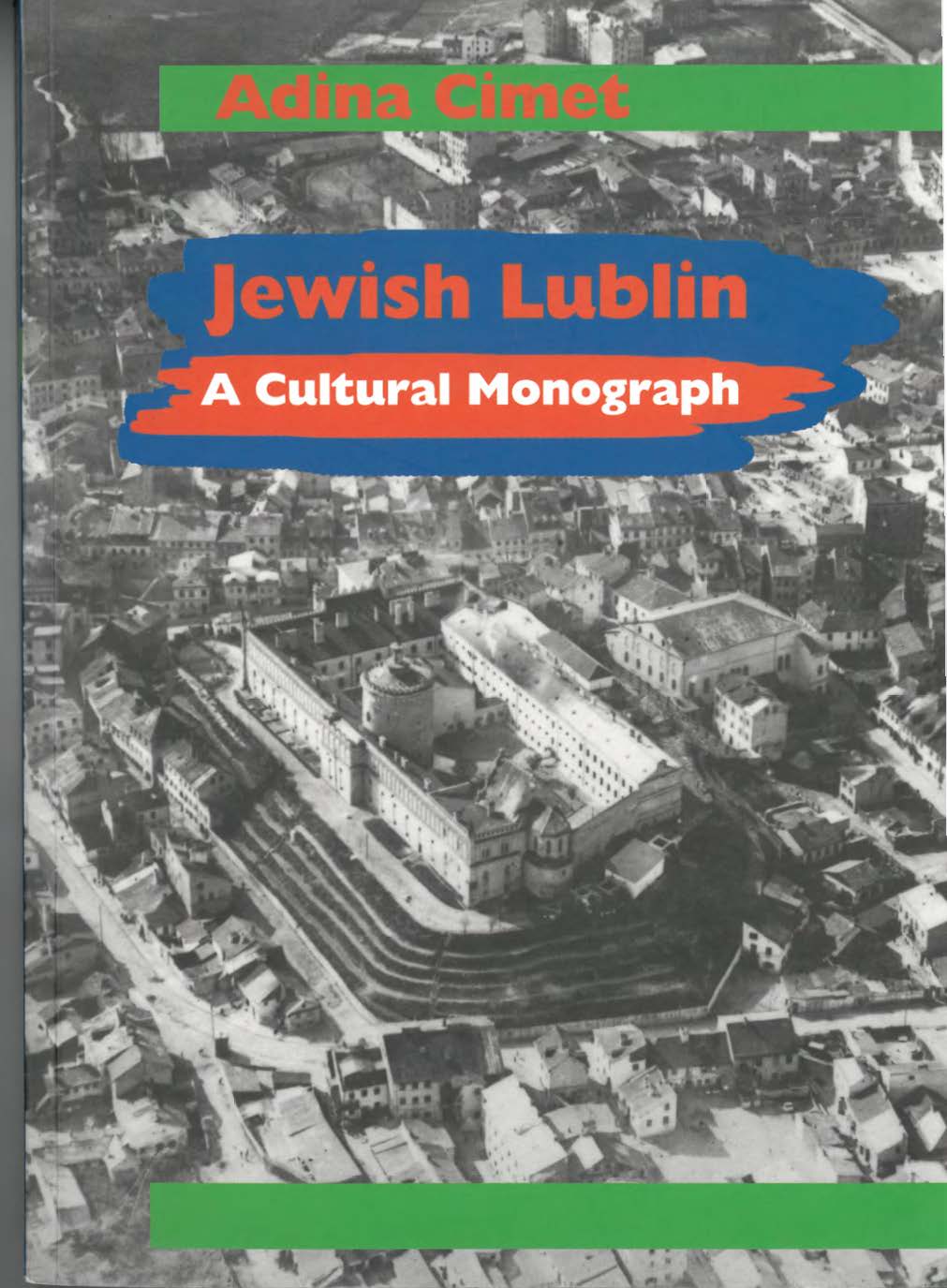

Jewish Lublin - A Cultural Monograph

This book revives the vanished Jewish world of Lublin—built over eight centuries yet absent from the city today—reconstructing its culture from surviving traces to honor its people and inspire a vision of peace and respect.

Lublin also had a "preacher's house" where visiting rabbis and scholars stayed and taught. There was also a chevra kaddisha (burial society), which collected funds and arranged for burials, both important functions within the Jewish community. There was an old Jewish cemetery, established in the 1500s, and a new cemetery set up early in the 19th century.

In the interwar period (1919-1939) a full range of Jewish schools existed within Lublin including religious, Yeshivot for talented older students, girls' schools (starting around the turn-of-the-century), secular and religious Zionist schools, Hebrew schools (starting in 1897), the Zionist Tarbut (Culture) schools, the CYSHO Bundist schools of the 1930s, and the Polish State schools. In the 20th century, cultural and educational integration between Lublin's Jews and Poles was still slow to take hold, but it had begun. An earlier failure at achieving the goal of integration, described in an 1817 letter from non-Jewish Lublin school administrators to their state superiors, exemplifies some of the difficulties presented. It is not possible, the administrators wrote, "to persuade the [Jewish] population to send their children to schools serving Catholic children jointly. The Jews, being unenlightened and sunk in superstitions, do not dare, despite our many rebukes, to dress their children in non-traditional clothing. They do not dare remove their skullcaps nor cut off their side-curls. Although the Jews in Lublin did approach [us] and expressed a desire to send their children to the elementary schools, when they learned of the terms of admission they stated that they were unable to fulfill those conditions."

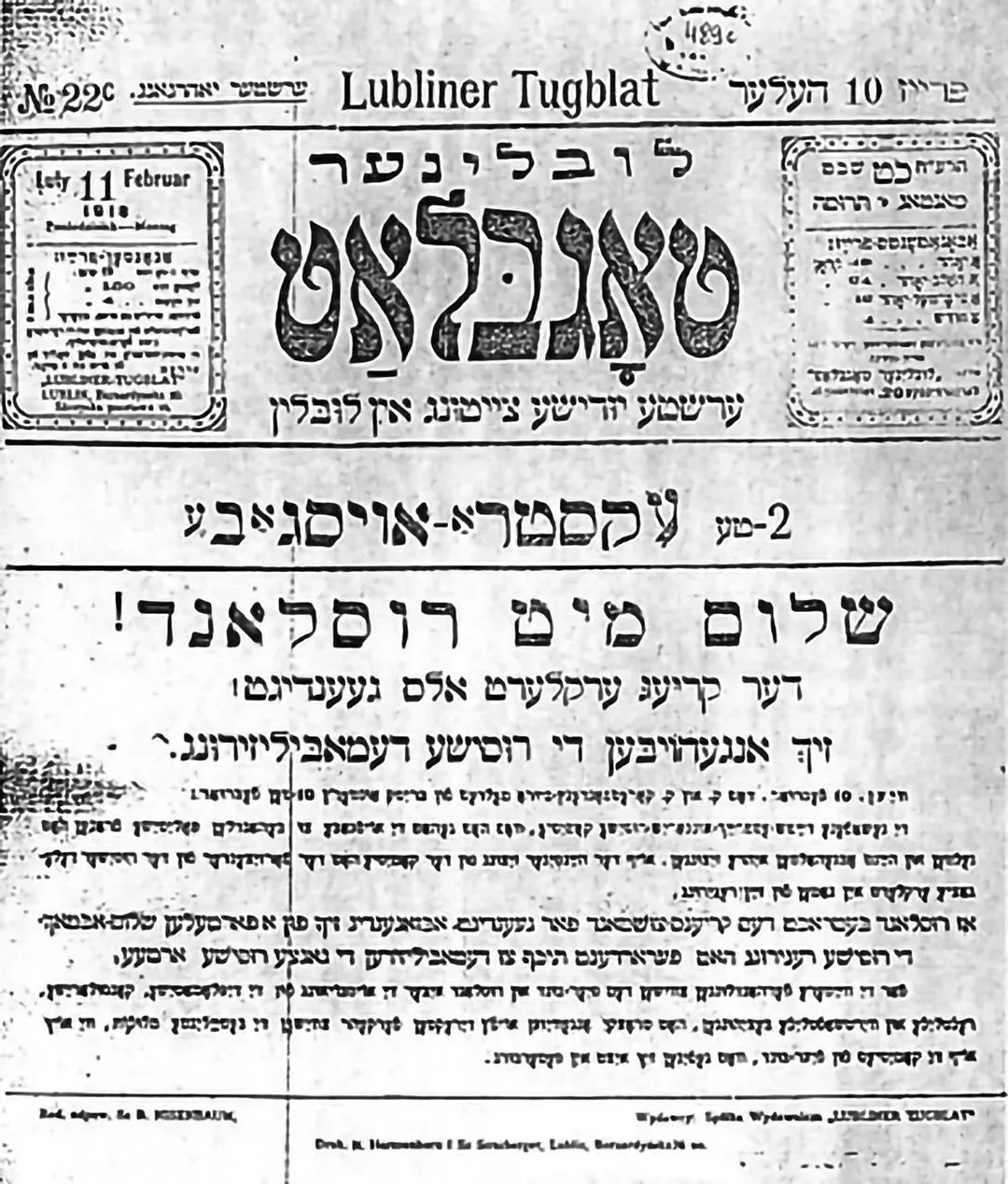

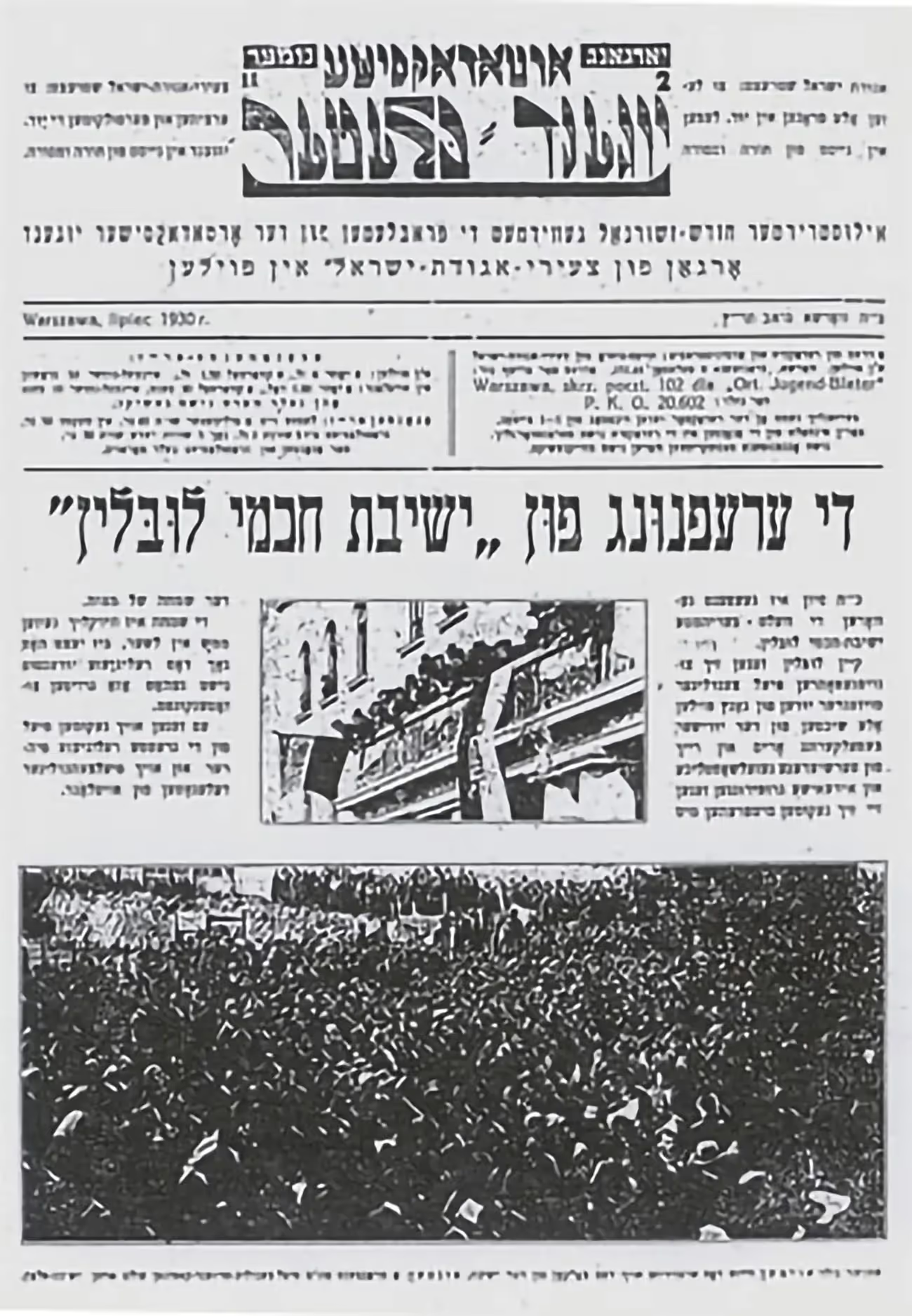

Meanwhile, as the social and political upheavals of the era visited Lublin late in the 19th century, a familiar battle between Zionists, Bundists, and religious Jews took place at every level of Jewish society, especially within the pages of newspapers (such as the daily Lubliner Togblat) and around community elections. However, in Lublin anti-Zionists maintained more influence than in many other cities. The religious Agudas Israel and the secular, Folkspartei vied for control, while Zionists inveighed against them both. No one party was able to gain the upper-hand in the struggle for local political leadership.

While always a reality for many of Lublin's Jews, poverty became particularly endemic to the community after Lublin lost its influence. The city was no longer anywhere near the center of Poland's economy and the boom had all but disappeared. The entire city suffered. Voluntary taxes - now paid by only a minority of Jews - could barely support the surviving welfare organizations, over-crowded hospitals, and orphanages. Nevertheless, life continued, and a wide range of social groups weathered the rough times: sports clubs, dramatic societies, orchestras, amateur theaters, library societies, and political youth groups, among others.

Lublin's Religious Communities

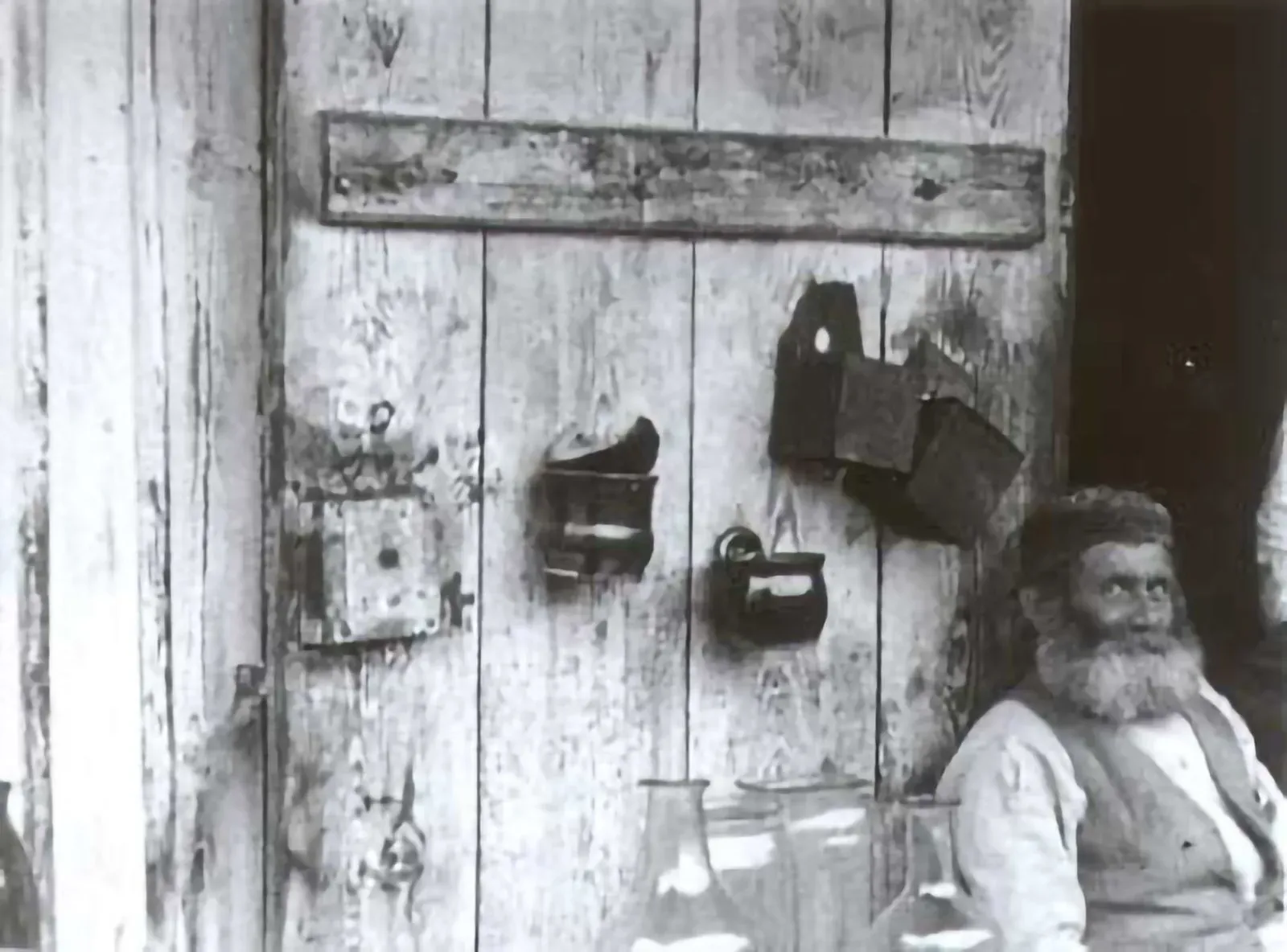

Lublin was especially known for its strong Hasidic community, which thrived until the Holocaust, even without the charismatic leaders of earlier years. Historically, Lublin was well-known for its great tzaddikim, sages who, unlike other rabbis, became larger-than-life spiritual mentors within their respective groups. Outside of the formal synagogue, Hasidim congregated in modest shtiblekh, simple houses of prayer and study that sprouted in the homes of community leaders. Lublin was full of such shtiblekh.

One of the founders of Polish Hasidism and Lublin's most important tzaddik was Ya'akov Yitzkhak ha-Levi Horovitz, known to his followers as "The Seer of Lublin." The Seer lived in the late-18th /early-19th centuries. He was widely believed to be a miracle-worker, a heroic figure of folktales who was said to cure infertility, predict the future, and able to levitate upon command. Legend also had it that he always wore blindfolds in order to sever himself from the wickedness of the world.

In the interwar period, the established Orthodox Jews had an upper hand and a great leader in Rabbi Meir Shapiro. He created a celebrated yeshiva, the Yeshivat Khakhmei Lublin (The Academy of Sages of Lublin), world-famous despite existing for only nine years before the war came. Rabbi Shapiro was a tireless scholar who traveled throughout the United States and Western Europe collecting the necessary funds to create the institution, making an extraordinary effort to return Lublin to its once revered status as a center of scholarship and religious life. His vision was to fashion a fully modern and established religious institution on a par with western universities, thereby lending legitimacy to a movement that was increasingly seen, especially by secularized Jews, as anachronistic and medieval. He achieved his goal in 1930 with a handsome building housing 200 students at a time, a library of over 10,000 religious texts, lecture halls, gardens and all the amenities that a modern yeshiva student might want.

Industry and Labor

As in Lvow and Crakow, many of Lublin's Jews were in the business of exporting Polish goods. They were able to help stimulate the local economy a bit during the 19th century, as vast Russian markets opened up to the western provinces. As industrial production increased, Lublin became a significant center for leather and tanning, profitable industries in which Jews were well-represented at all levels. Jews owned many of Lublin's tanning factories and also made up a great share of the workforce. Interestingly enough, because Lublin had a strong religious community, a large percentage of those leather workers were Hasidim, and it was within their ranks that the city's famous labor movement got its start. After workers struck against poor factory conditions, local labor unions were formed and, eventually, attracted hundreds of members. Soon enough, the entire city was caught up in the international movement to organize workers under the banner of socialism.

So great was the rise of political dissidence and labor unrest at the turn-of-the-20th century that Russian authorities converted the former royal castle, still abutting the now-riled-up Jewish quarter, into a jail for political prisoners. One organization, MOPR (a Russian acronym for the International Society for the Aid of Revolutionaries) worked in Lublin (and elsewhere) in order to aid the many Jewish prisoners arrested for their political views, and assisted both inmates and their families with food, clothes, and legal support.

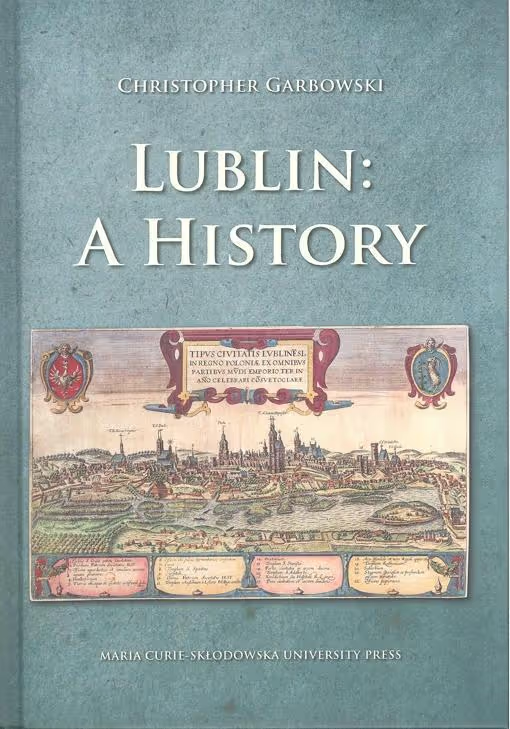

Lublin: A History

Christopher Garbowski

Ed. Maria Curie-Sklodowska University Press, 2018

.avif)