Mon arrivée au monde n'a pas été heureuse

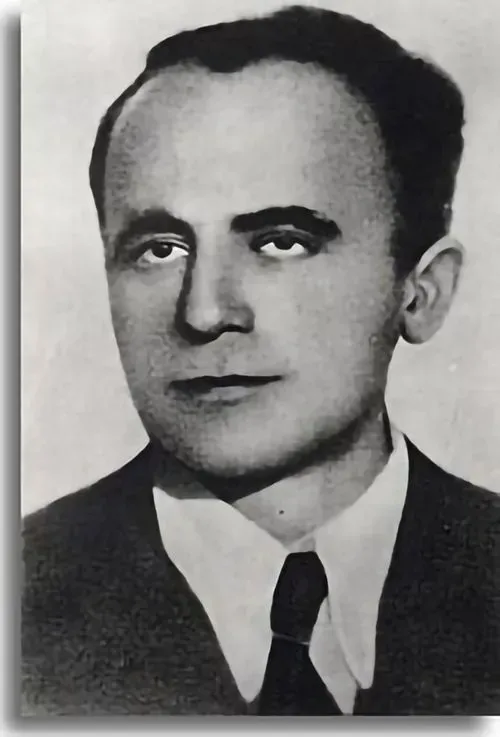

« G.S. » a écrit son autobiographie en polonais en 1939, à l'âge de 21 ans, dans le cadre d'un concours de rédaction parrainé par l'Institut YIVO pour la recherche juive. YIVO, qui se trouvait alors à Vilna, en Pologne, a invité de jeunes juifs polonais âgés de 16 à 22 ans à écrire et à envoyer des histoires de vie.

To protect her anonymity, G.S.'s home town is known here simply as "M" and her parents' names have been disguised as well. YIVO guaranteed anonymity in order that the entrants should feel comfortable being honest about their feelings and lives.

I was born in 1918 in M., the second daughter of H. and H. S. My father works as a manager of rural estates. My arrival into the world wasn't a happy one. My parents had wanted a son very much. When they were expecting their first child, they had hoped for a boy, and when it turned out that their second child was also a girl my mother took an instant dislike to me, which I have felt all my life.

I run away from home and begin working as a tailor

Once, during my summer vacation following the sixth grade, I could stand it no longer and ran away from home. I moved in with my aunt, who also lived in W., but on another street.

With my cousins' help I found a job with a tailor, where I worked as a finisher of trousers. I was earning six to eight zloty a week, and I gave all the money to my aunt in exchange for room and board. My aunt didn't want to accept it, but I insisted. She finally agreed, and from time to time she would use some of the money to buy me something to wear.

I felt comfortable at the tailor shop and even grew to like my job, but there were moments when I was gripped by feelings of regret about not going to school and about my unfulfilled dreams of studying medicine.

After several months at this job, I ran into my teacher in the street. When she asked me why I wasn't attending school, I told her that I couldn't because I had to work. She became indignant and insisted that I absolutely had to return to school, and she assured me that a student would be found for me to tutor in the afternoons.

I had to agree. I went back home, quickly studied the material I had missed, and in the second semester I returned to school.

I Return Home and enroll in School

My teachers and relatives talked me into enrolling in a teachers' seminary, where I could graduate in less time than at other schools. They also believed that this degree would make it easier for me to find a job.

I took their advice and enrolled in the seminary. I attended classes and tutored in the afternoons. Mother thought this was foolish and claimed my studies would be of no use to me. My sister, having graduated from elementary school, was learning to sew, and this pleased Mother much more.

Theythought that I should drop out of school, say at home, and help Mother

[...]A silent feud developed between my parents and me. They both now thought that I should drop out of school, stay at home, and help Mother. But I was stubborn and prevailed, enrolling in the seminary in Zloczów.

However, I attended the school only for a few months until the end of the school year. During summer vacation, Father managed to convince me that attending the seminary was a waste of money, and that as a Jew I would never get a teaching job. Besides, the program at the seminary lasted five years, and tuition was so high!

However, since I desperately wanted to study and become accomplished, Father and I decided that at the beginning of the school year I would enroll in a commercial school. Despite the openly anti-Semitic attitudes that increasingly prevailed, we firmly believed that I would end up working in an office.

During that summer vacation I was depressed. Although I didn't work outside the house, as I had the two previous summers, my thoughts were unhappy. It was so sad to abandon my dreams and start something else again. Once before, I'd gotten over the disappointment that I wasn't going to study medicine; I had consoled myself that I would be a teacher, and I liked this idea. Now I was leaving it behind to take up something else again.

That year my brother passed the gymnasium entrance examination, and both of us went to school in Zloczów. We rented a room there; our sister kept house for us, our parents paid for my brother, and I earned my keep by tutoring. I had promised to do this, and on this condition I was given permission to go to school.

.avif)

It wasn't hard for me to find students to tutor, because I earned a reputation as a bright student very quickly, and my professors liked me. I had about five or six tutorials, which paid enough to cover my tuition payments as well as my room and board. Clothing was always a problem.

The best of my private students was with a classmate of mine, who later became my best friend. She was a Catholic, the daughter of a well-to-do engineer. She was staying in Zloczów with her grandmother, who was the wife of a court councilor.

For tutoring her I received thirty-five and later forty zloty a month; her grandmother also invited me for a snack every afternoon

We became very close friends, this girl and I, and this friendship--despite the difference of religion, ideology, and now the distance between us--has lasted to this very day.

The letters my friend has sent me lately are quite interesting. She refers to me in them as her sister and asks me not to take to heart certain Catholics' attitudes toward the Jews, because--in her view--these Catholics constitute a small minority, while the rest recognize the equality of all.

I told her about my latest wishes and dreams, which involved going to Palestine. I joined the Betar youth movement. Many of my friends also joined, but we did so secretly, so that no one at school would know, as it was strictly forbidden.

I remember fondly those evenings, when, after exhausting tutorials, I would drop by the Betar headquarters, at least for a short while. It was always noisy and cheerful there, and when I left I always felt refreshed. Whenever time allowed, I also tried to be involved and help out.

Unfortunately, I always had very little time. In addition to my studies and tutorials, I also signed up for classes in French and Hebrew, but later I had to drop them due to lack of time.

I myself don't exactly know how it happened that, despite my upbringing, such a strong feeling of Jewishness awoke in me, but the strongest influence was the anti-Semitism that flourished in schools then.

My sister and brother also became ardent Zionists at the time, and this had an influence on our parents. To the extent that they could, they began to contribute to Jewish causes, shop in Jewish stores, and socialize in Jewish circles. Today, a portrait of Herzl and a map of Palestine hang over Father's desk.

I search for work and confront anti-Semitism

My dreams were now more or less as follows: to find an office job, work there until I saved enough money to go to Palestine, buy some decent clothing, and leave for Palestine. There I would work on a farm, then buy a little house with a small garden, a cow--in a word, I'd have a small place of my own, where I could bustle about, a homeowner and homemaker.

Alas, these, too, remained merely dreams. I kept reading ads in all the newspapers and sending in applications, I pursued connections through my friends, but all in vain.

The GREATEST OBSTACLE to getting a job was my religion

I came to realize this when there were two job openings, one at an insurance company, the other in the town hall.

I approached the president of the trade school association, who liked me very much. He was also the mayor of Zloczów. He knew me from school; I was always sent as the commercial school's representative to wish him all the best on his name-day, and he had always promised to help me.

Now he said to me, "I could help you if you weren't Jewish." This was very painful for me. Was it my fault that I was born Jewish? Did anyone ask my opinion about whom I wanted as parents, or who I wanted to be? Despite being Jewish, hadn't I always participated in every patriotic event? I was the best student in school, and my Polish compositions were read aloud in class as models of good writing. And how much devotion and love for the country in which I was born and raised was contained in them!

I begin to work towards my dream

As soon as I joined the movement, a Betar commander began to follow me around constantly.

At first, I paid no attention to him--just as I had ignored my schoolmates in this respect--simply because I never had time even to engage in casual conversation with anyone. I noticed him only when my girlfriends started teasing me, and when our names were mentioned together more and more often.

I liked him. Although he was short and not particularly handsome, there was something about him that I found attractive. He was exceptionally intelligent, and he was so engaging that it was impossible to be bored in his company.

At first he only walked me home from our meetings, but later, after I graduated from school, we went everywhere together. He also tried to help me find a job, although without success. He loved me; I knew it, and I also got used to him and fell very much in love with him.

When summer vacation was over and I had nothing to do, he suggested that we both go on hakhshara, and then we would certainly manage to get certificates to emigrate to Palestine. This was more likely because he was a commander and had greater influence; in fact, he had already earned a certificate. Once again, I had a dream: we would complete hakhsharah and leave together for Palestine.

We went to work on a farm in Kalinka. A new life began for me, doing physical labor that I hadn't tried before. Although at first my body ached, I was in rather good spirits. I raked hay, dug up potatoes, milked cows, and so on.[...]

I was sent to complete my hakhsharah in Zbaraz. There I chopped wood at first, then I did laundry, and in the end I kept house and cooked for the unit. The organized activities were very enjoyable. In the evenings, after work, we studied Hebrew and attended lectures on the geography of Palestine, Jewish history, and so on.

Of course, some unpleasant conflicts were unavoidable. There was a girl in the unit who--I don't know why--disliked me. She conspired with a few other girls, and they began to make fun of me. Their reason was that I couldn't speak Yiddish. Was it my fault that I never heard a word of Yiddish spoken at home? And where was I to learn it--at school?

The other girls didn't know it, but I have a contrary nature; when someone annoys me or yells at me without justification, I will sooner pretend that I don't care rather that explain or make excuses for myself. I would have explained, but only if they had asked me politely, without accusations and shouting.

This squabbling led to arguments in the unit, and as a result I acquired the nickname of "shikse". Later, after that nasty girl left, we all got along.

I Leave for Lwów, My Boyfriend Leaves for Palestine

So as not to upset Father, I told him--this was just a week after my return from hakhsharah--that a friend of mine had found me a job in Lwów, and this was why I was leaving. Father lent me some money for the trip, behind Mother's back. I packed some of my belongings and left for Lwów.

This was the most daring move I had made in my life. Before my departure my boyfriend contacted me, and we made up with each other. We came to realize that we truly loved each other and that our quarrels were silly.

He was leaving for Palestine. He couldn't take me along because he wasn't traveling legally, but he promised that in a short time he would bring me over. We promised to love and be loyal to each other, and he left for Palestine on the same day that I left for Lwów.

I found it very difficult to part from him. Although I trusted him completely and he assured me that we would see each other in a few months, I had some terrible premonition that I would never see him again.

Four months later he was killed by Arabs, and with him my youth and my pleasure in living ended forever.

I search for work in an unfamiliar city

Someone who has never experienced it certainly will not understand what it means to hunt for a job in a big and completely unfamiliar city. I simply went from store to store, from office to office, and asked for a job.

Some sent me off politely, but with nothing; others snapped at me rudely. Some made promises they had no intention of keeping; still others made unpleasant remarks or indecent proposals.

I walked along streets that I didn't know and looked jealously at people who were employed. How I envied the salesgirls I saw bustling about in the stores! It seemed to me that, as I was told I wasn't needed everywhere I had asked for a job, I really wasn't needed in this world.

...

In the meantime, the members of the unit hadn't asked me for money. To make sure that they wouldn't notice I wasn't working, I didn't eat lunch there, but ate only breakfast and supper, which consisted of terrible coffee and a piece of bread.

This couldn't satisfy my hunger, of course; I was starving. Quite often I found myself standing in front of restaurants and pastry shops, greedily looking at food. In order to feel less hungry, I tried to upset my stomach. One day I ate a pickle on an empty stomach and then an apple, and with my last pennies I bought some buttermilk. If I had been the closely watched child of affluent parents, I am sure I would have caught typhus, but since I was very poor and nobody cared about me, all I got was a mild case of diarrhea and a much bigger appetite.

...

So I said goodbye to the Betar unit and moved here, where I have been to this day--that is, for two years. I am in charge of two boys. The older one is seven years old, so I have to tutor him; the younger boy is two years old, and I take him for walks in the stroller.

At first I felt very uneasy and embarrassed, but now I've gotten used to it. I receive room and board plus twenty-five zloty a month (at first I was paid only twenty). Of this I send ten zloty every month to my parents and use the remaining fifteen zloty to buy clothing and to save.

I haven't as yet completely resigned myself to fate, and I don't want to spend my entire life doing this kind of work. Despite everything, I intend to leave for Palestine and work there.

I have persuaded my employer to let me have two free evenings a week to study Hebrew. Perhaps I will go to Palestine, so this will be useful. I would gladly learn other languages as well, but unfortunately I have no time.

Also, I no longer attend Betar meetings; I have neither the time nor the drive. Jobs such as this one are very exhausting; the children are annoying and mischievous. The mothers have whims and "moods," and one has to endure it all patiently.

If I had the money, I would emigrate illegally, but I don't. I hope God will give me strength and endurance so that I can stay here long enough to save money for the trip. Then I'll leave for Palestine and start a new life. I hope that its description will be more pleasant and cheerful than this one.