Warsaw

Warsaw Warszawa

.avif)

History

Warsaw, the grand capital of Poland and its largest city, was one of the great centers of Jewish culture and politics, before its near-complete destruction during World War II. However, Warsaw sat for centuries, before gaining preeminence, as an inconsequential rural outpost in the kingdom of Mazovia, which was a relatively unproductive landscape of rye and potatoes. Founded in the 1300s, the city grew very slowly over the centuries. Warsaw took its importance largely from its strategic military position, situated on a terrace above the great Vistula River between the ports of Danzig and Cracow. Jews began trickling into the town during the 14th century and as the modest Jewish population grew, they were met with increasing levels of hostility. Frequently barred entry within the city walls, in 1527 Jews were finally banned from the city under the provision of de non tolerandis judaeis, a ban that lasted for the next 250 years. Such outright exclusion led to the formation of Jewish cities outside the city walls - a city outside a city, a "parapolis."

Modern Warsaw

By the beginning of the 20th century, Warsaw was a phenomenally compact and dense city (three times denser than Paris and Moscow). The slums - both Jewish and Polish - were shocking to middle-class sensibilities, marred by bad hygiene, poor or non-existent plumbing, and inadequate sewers, but also elegant boulevards and solid middle class suburbs. Warsaw was home to Europe's largest Jewish community for the first half of the 20th century. The population included some 400,000 Jews on the eve of the Holocaust, which comprised about one-third of the city's total population.

The main Jewish quarter from the 19th century onward was located in the northwestern part of the city. The area housed 250,000 Jewish souls in several smaller neighborhoods and teemed with energy. Because of its intense poverty and conspicuous Jewish presence, it was a place often feared and hated by Poles. The area had "an invisible wall which separated the quarter from the rest of the city," Bernard Singer, an observer from the time, wrote.

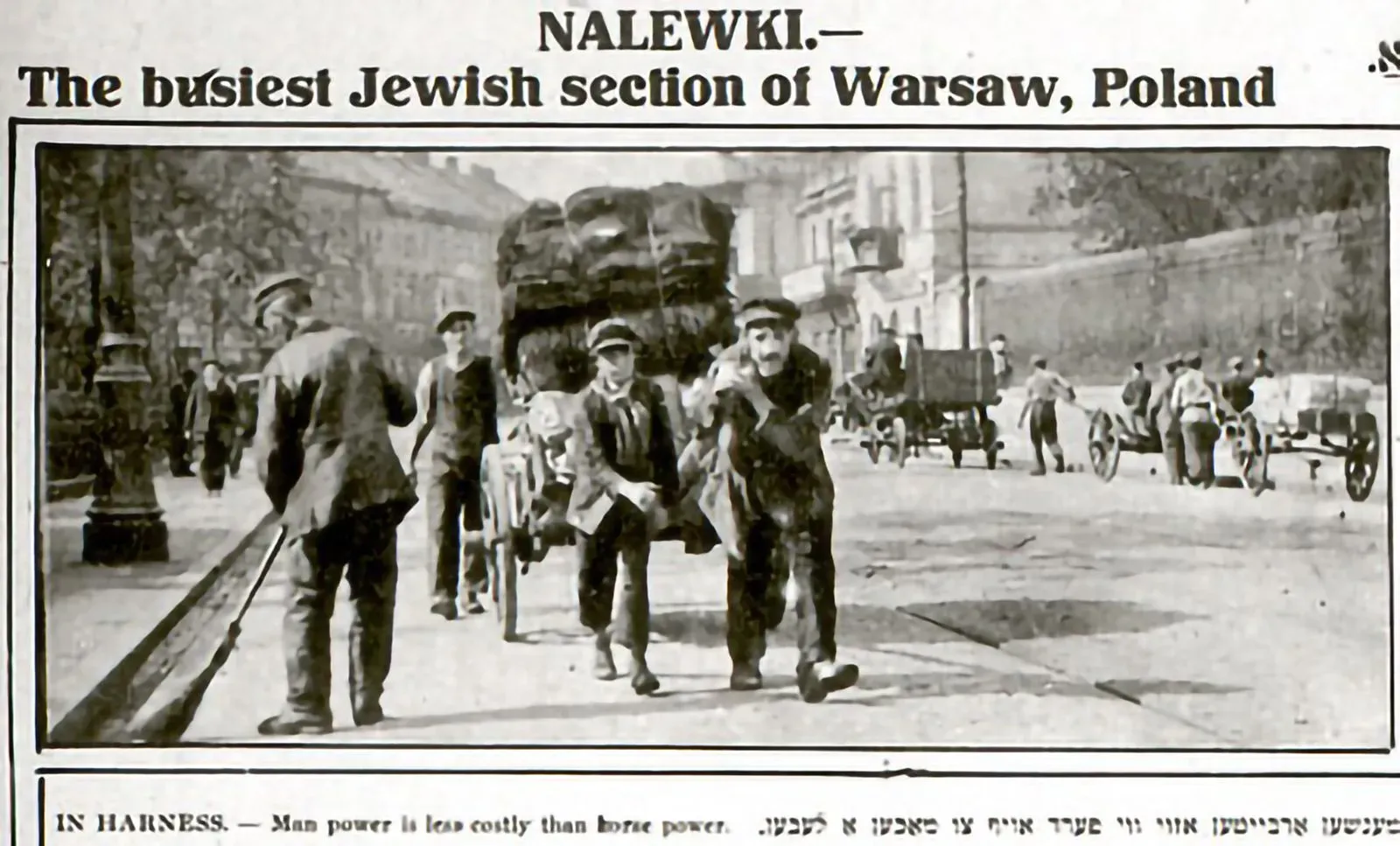

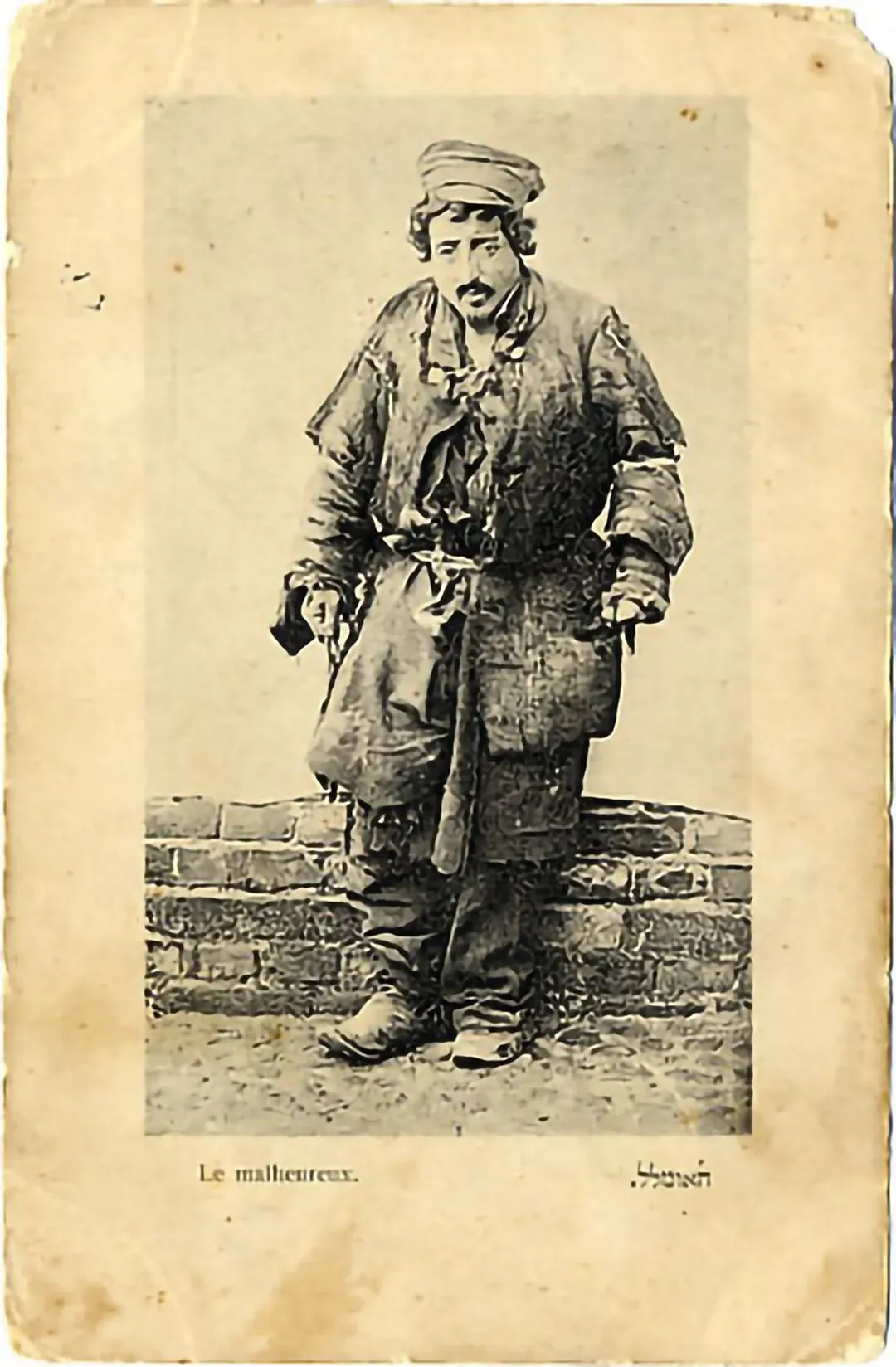

Typical depictions of Warsaw's Jewish community during the last century of its existence contained horrified and hyperbolic accounts of misery and wretchedness. Kurt Aram, a New York Times reporter who visited the city in 1914, couldn't restrain his astonishment at the filth, beggary, and human overcrowding (like "herrings"). "The mass of this population naturally possess but one idea-how to get bread. Their mode of life leaves them no time for any other thoughts," Aram wrote. Regardless of class or occupation, Nalewki Street was the center of neighborhood activities, a hectic thoroughfare awash with shouting peddlers, artisans, the unemployed, and the suspiciously employed. The great Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer described Nalewki as a dizzying boulevard,

"Lined with 4- and 5- story buildings with wide entrances, plastered with signs in and buttons, umbrellas and silk…Wooden platforms were piled high with wares...At the entrance to a store a revolving door spun around, swallowing up and disgorging people as though they were caught up in some sort of mad dance."

In the 1930s, 75 percent of Warsaw's Jews lived in poverty. As a consequence of this, black markets and underworld ventures operated everywhere. Despite the poverty, and all the harsh conditions that might catch the eye of a visiting reporter, Warsaw was a major cultural center. The northwestern part of the city was also home to Warsaw's Jewish middle and upper-class elites, who constituted a relatively small number, but were a key part of the city's bourgeoisie. Warsaw Jews were heavily represented in trade and industry, at all rungs of the economic ladder, from street-peddlers and cigar rollers, to established craftsmen, bankers and entrepreneurs. This section of the city was a major center for manufacturing of all kinds, but textiles and tobacco processing were particularly important and employed thousands.

Institutions

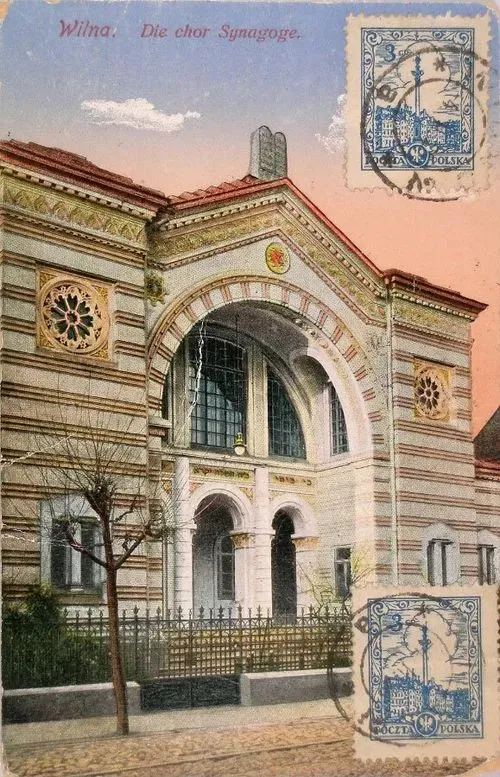

The city's most opulent synagogue and best-known Jewish landmark was the Great Synagogue on Tlomackie Street, a daunting Greco-Roman structure completed in 1878, designed by wealthy, culturally assimilated Jews as a nod toward the Russian monarchy.The city's most opulent synagogue and best-known Jewish landmark was the Great Synagogue on Tlomackie Street, a daunting Greco-Roman structure completed in 1878, designed by wealthy, culturally assimilated Jews as a nod toward the Russian monarchy.

The synagogue seated 1,100 people and, like the German synagogue, featured an Orthodox liturgy with modern accents, including prayer books translated into Polish. After the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, the Nazis destroyed the building as a public display of their power and ideology, declaring that the Jewish community was no more. During the long history of Orthodox and Hasidic religious centrality, the traditional model of schooling held sway: kheyder for small boys, yeshivot for young men. During the mid-19th century, 90 percent of Warsaw's Jewish children attended kheyder, of which there were hundreds in the city. These kheydorim provided basic instruction in Hebrew and Jewish prayer, using Yiddish as the language of communication. Among reformers, these schools were seen as dated and inadequate, being notorious for bad hygiene and cramped quarters. As in centuries past, the yeshiva served as higher education for selected young men delving further into study of Talmud and Jewish law. Gradually, however, as the general break-up of Orthodox prominence took hold in the late-19th century, new schools began to appear from an Orthodox girls' schools known as Beis Yakov to Yiddish schools, and including Russian and Polish state schools, along with modern Hebrew-language schools and trade schools.

Political Movements

Change came in the form of the uprooting nature of the industrial revolution and all that it spawned: mass migration in every direction, urbanization, railroad construction, factories, labor unions, and the increased prestige of Western ideas. It was in the Warsaw of poverty, dislocation, and ferment where new, alternative ideas for Jewish survival took the firmest hold. At the end of the 19th century, the city was engulfed in cultural and political change, which gradually swept thousands of Jews out of traditional Judaism and into dynamic new political movements.

In the 1880s, new organizations and political parties sprouted dramatically and each idea, whether Socialist, Zionist, or traditionalist, vied with the others for a more prominent role in the lives of Warsaw's Jews. There was a flurry of activity, with scores of groups and, perhaps at best, one common goal: full Jewish equal rights. With its Zionist groups for adults and youths, labor unions, moderate socialist groups, Communists, and religious Jews, Warsaw functioned as a central battleground in which each group struggled to attain 'the world's predominant Jewish worldview.'

After 1918, Jews participated in mainstream Polish politics in the newly formed Republic. The ongoing struggles of the early 20th century eventually resulted in Warsaw's kehilla yielding power to the Zionists, who then lost it in 1936 to the Bund. The Bund was an inexhaustible source of energy, organizing strikes, demonstrations, promoting of Yiddish culture, and, at times, opposition to Zionism. One key belief that the Bund and the Zionists held in common was that both sought a new language that could be used to attain practical goals, political changes, and rights for all Jews.

The Press

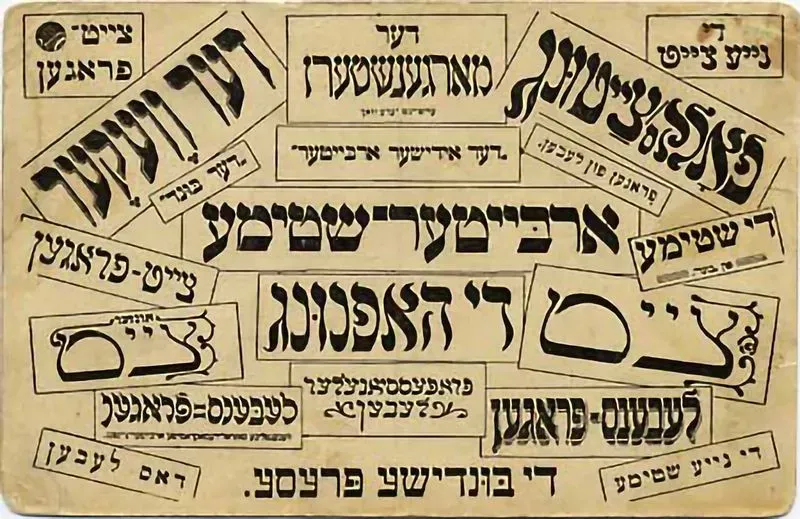

One of Warsaw's most fertile and dynamic institutions was its great Jewish press, through which the city's intellectual debate was concretely realized. The number of publications in Warsaw skyrocketed during the late 19th century - among both Poles and Jews - and constituted one of the highest concentrations of Jewish papers in the world. Dailies, weeklies, and journals, whether in Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, or German, were effective vehicles for expressing community ideas, politics, and ethnic identity.

In 1862, the first Hebrew paper, Ha-Zefirah (The Dawn) was established. It was also subtly secular and celebrated the resurgence of the Hebrew language. During its peak readership at the turn-of-the-twentieth century, Ha-Zefirah morphed into a popular Zionist organ. Another early weekly, Izraelita, published in Polish, appeared in 1866. But the true flowering of the Jewish press occurred along with the flourishing Yiddish culture and language, greatly boosted when Russian authorities loosened restrictions on the Press in 1905, just in time for the torrent of political dialogue that gripped all of the Jewish Eastern European world.

The first Yiddish daily was Der Veg (The Way), debuting in 1905, followed by the famously successful Yidisher Togblat (Jewish Daily Paper), which set the standard for popular Jewish newspapers. "The Togblat's two basic goals," Stephen D. Corrsin explained in his work on Warsaw's Jews before World War I, "were to be cheap (one kopeck), and to win readers through aggressive and lively reporting and sensationalism." In 1906, it printed "an average press run of 54,200 copies, which made it the most popular newspaper in any language anywhere in the partitioned Polish lands."

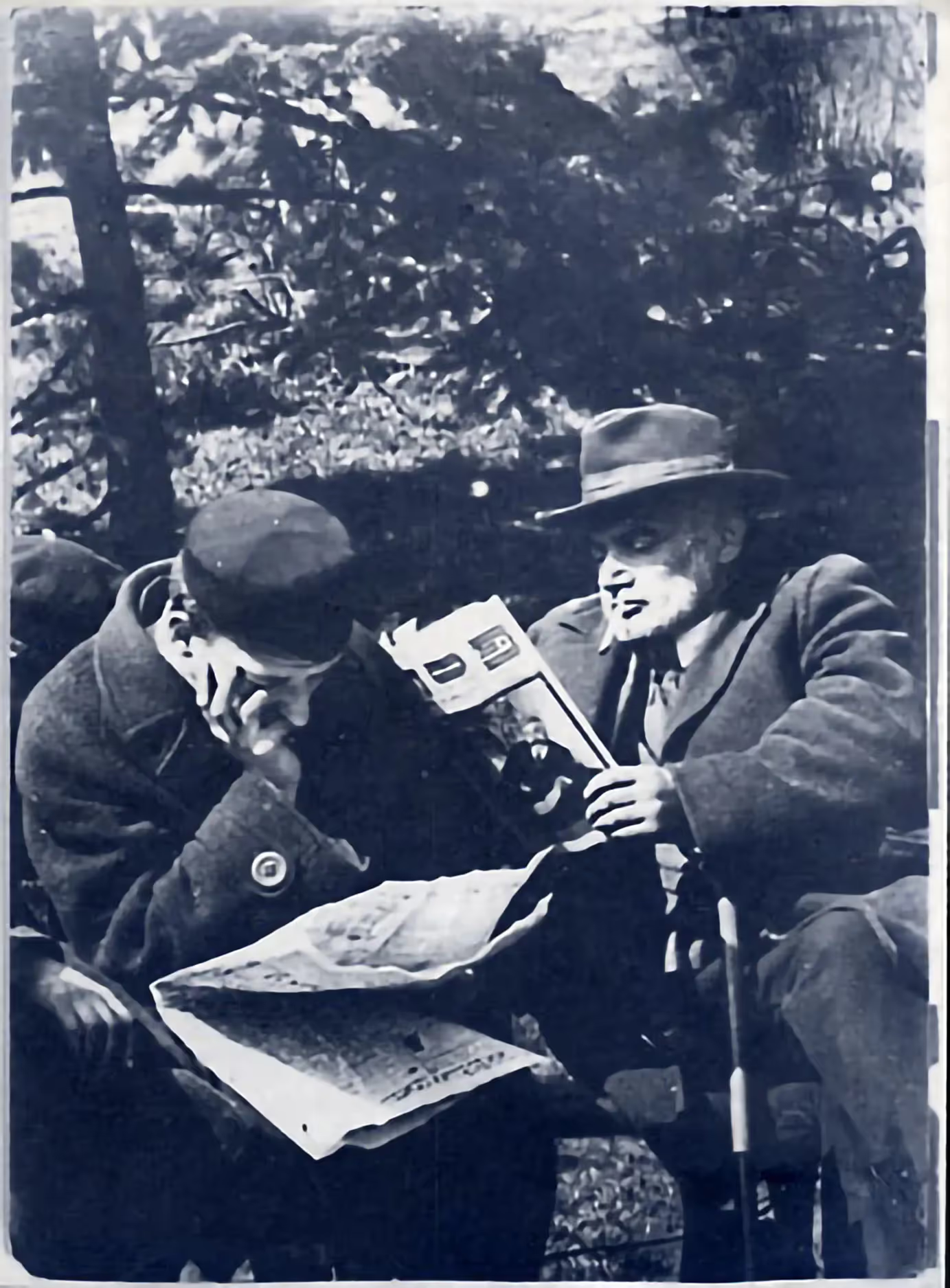

At the height of popularity of Warsaw's Yiddish press, the field attracted talented writers from many corners of the Jewish world, enticing journalists who were seeking to be a part of a great cultural elite, to join the ranks of artists, novelists, and intellectual bohemians.

Then and Now

Walking through Warsaw today, there are very few indications of the great Jewish presence that once made this city the premier destination for an emerging Jewish cosmopolitan class.

There is no Yiddish press, and there are no Yiddish writers. No Yiddish schools and no Jewish children. There is only a seasonal Yiddish theater performed by non-Jewish actors, an effort to pay tribute to a great institution that is no more. The Main Synagogue has been refurbished in recent years, after having been desecrated. A new museum, already under construction, is being erected in the plaza in front of the monument honoring the uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto Jews, but the names of those who fought the ghetto battle are largely unknown to passersby. A walk through the sprawling old Jewish cemetery, which does remain almost intact, provides a glimpse of the colorful, and occasionally flamboyant, personalities that once resided side-by-side with the working-class Jewish masses in what was the most populous Jewish city in Eastern Europe. This is a lonely testament to the Jewish life that once thrived in Warsaw, a story that now continues with the remnant survivors now in other lands.

.avif)