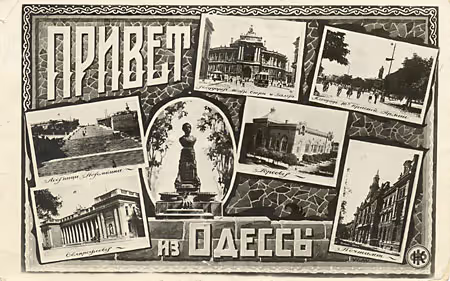

Odessa

History and Settlement

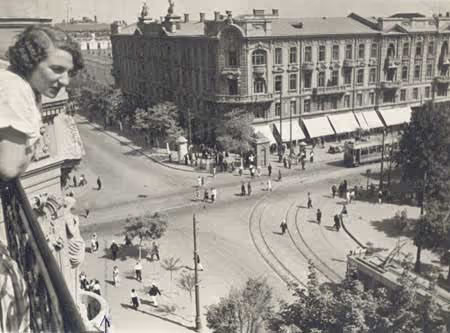

Jewish migrants flocked to Odessa in substantial numbers during the 19th century, seeking work, safety, and relative social freedom. At its heyday near the turn of the 20th century, Odessa boasted Europe's second-largest Jewish community after Warsaw, one that developed a rich secular culture of arts and letters, theater, and political activism. Upon arrival, many Jews initially staked out their standard roles as small-scale merchants and craftsmen. Hoped to gain a foothold in the lucrative wheat business, an industry in Odessa then commanded by Greek, Italian, and French companies.

Beginning as grain classifiers, sorters, and weighers, Jews gradually gained larger roles in the export business and, in a move that brought considerable hostility from competitors, in the 1860s broke the wheat monopolies, eventually achieving a dominant role in the trade. Jews also made up a major portion of those who worked in Odessa's liberal professions - in medicine, law, architecture - and formed a large industrial proletariat of factory workers and laborers.

In 1939, Odessa's Jewish community numbered some 180,000, about one-third of the city's population. The largest Jewish quarter in Odessa was the poor and overcrowded Moldavanska, a former suburb that once housed Russian military barracks. During the early 20th century the area contained rough slums notorious for gangsters, black-market swindlers, prostitution and other urban vices. A series of nearby limestone quarries offered secret catacombs for hiding stolen goods and contraband. These same catacombs were used and during World War II for hiding Ukrainian and Jewish partisans.

Plurality and Pogroms

Some cultural integration into the larger Russian society did exist for Jews in diverse and polyglot Odessa. But for the most part Odessa's many ethnic groups tended to keep each to their own. They maintained their individual mother languages - Yiddish, Ukrainian, Greek - and formed their own cultural institutions. One exception to this rule was the general enthusiasm for Opera, a cultural obsession that crossed ethnic lines. When Italian singers came to the city to perform, Odessa's opera enthusiasts banded together in support of one diva or another, naming their groups after that diva. Whereas Greeks and Italians would often agree on one favorite diva, Jews rallied behind another!

Unfortunately in the larger breadth of Odessa's history, ethnic tensions were rarely resolved so peacefully. As numbers of Jews increased during the 19th century, and as their economic visibility grew, they periodically became the targeted victims of well-organized campaigns of violence. Virtually every sector of the larger Christian populace participated in this violence including Greek exporters, Ukrainian intellectuals, Russian businessmen, and czarist authorities exploiting the angers and fears of scapegoat-hungry mobs.

The first pogrom (meaning "devastation" in Russian) occurred in 1891 in Odessa. The last pogrom in the city was in 1905, a gruesome massacre lasting four days and claiming hundreds of Jewish lives. This conspiracy of violence repeatedly visited upon Jews in Europe was the final proof for many Odessa Jews that they would never be welcome asfull citizens, and lent tremendous credibility to the burgeoning Zionist movement.

Community Institutions

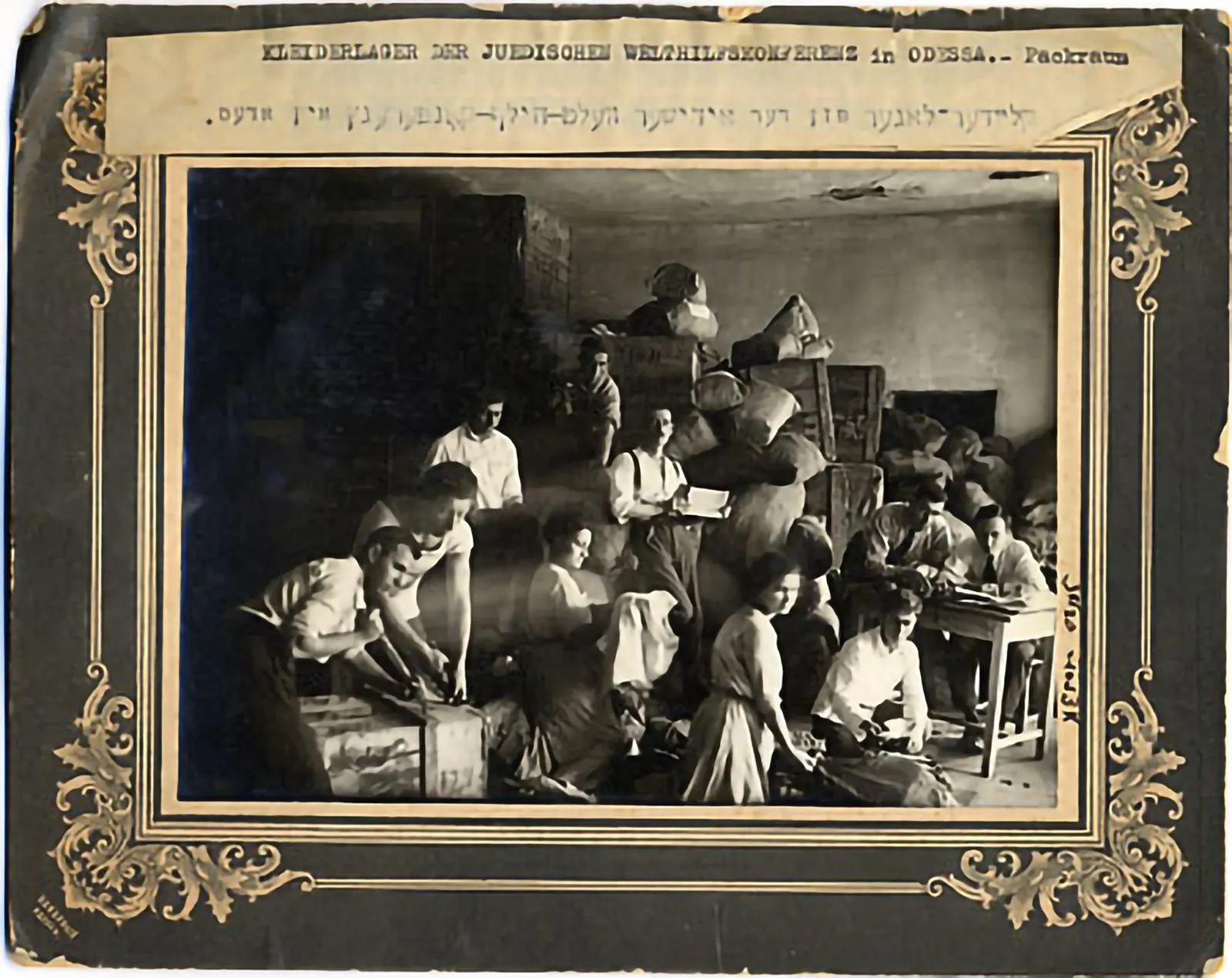

Though still a tiny community in 1797, Odessa's Jews were quick to establish a cemetery and Khevra Kaddisha (Burial Society) called the Gemilut Khesed Shel Emet (Help Society). In 1798, a modest synagogue was built and the kehilla (Board) was formed to govern and administer to the Jewish community. Supplementing the charitable work of the kehilla, Odessa's philanthropists set up summer camps for invalid children, soup kitchens, day-care for the children of laborers, orphanages, a 250 bed home for the aged, and a well-endowed hospital to serve sick Jews from around the region.

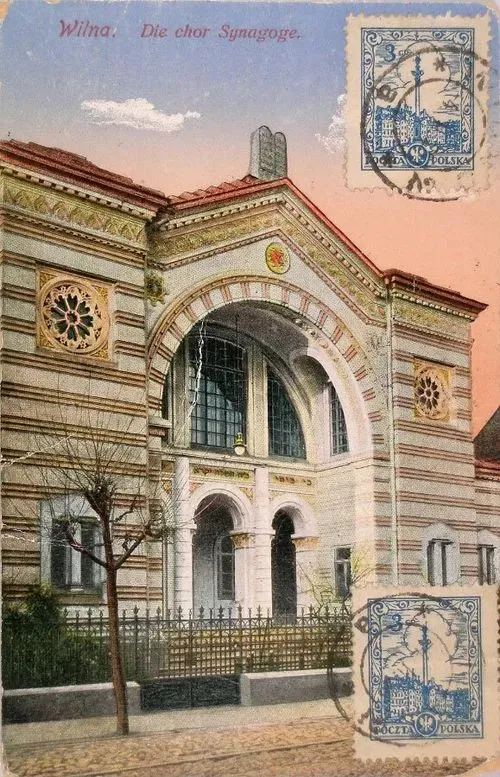

Though not a stronghold of Hasidism or other traditional orthodoxy, Odessa once housed dozens of synagogues and prayer-houses. Distinguished by occupation - butchers, flour-dealers, peddlers, and so on - trade members each founded their own Beis Medresh (small study and prayer house). The first of the city's major synagogues was the Main Synagogue, built on the corner of Richelevskaya Street and Yevreiskaya (Jewish) Street soon after the founding of the community. By the mid-19th century, the old building was crumbling and the community raised funds to replace it with a more permanent and attractive structure built in the Italian Renaissance style. As with all but one of Odessa's synagogues, it was closed in the 1920s by the Communist government crackdown against religion.

Odessa's more secular Jews organized the "Broder" Shul (synagogue), constructed in 1840, and rebuilt in 1863. Notably this was the first synagogue in Russia to feature a modern church-like choir (sixty years later and organ was also added), which launched a trend that is still followed within Reform Jewish temples. The Remeslennaya Street Synagogue, - a simple one-story building split between a tailors' congregation and the Malbish Arumim (Clothing for the Naked) philanthropic Society - was also built during the mid-19th century. This synagogue was closed in 1920 and for decades was used as a warehouse It was finally returned to the Jewish community in 1992. Today, after considerable renovation, the building houses the BeitHabad congregation of Lubavitch Hasidim, who share it with other Jewish organizations. One of the only active congregations in Odessa today, Beit-Habad is an ironic renewal of Hasidism in a city that was always better known as a center for liberal Jewish traditions.

Schools

Because Odessa was such a modern and liberal city, there was an exceptionally strong secular ethic among its Jews. Nevertheless, the city contained many of the religious schools common to every other large Jewish community, including a famous yeshiva headed by Rabbi Chaim Tchernowitz, where scholars such as the great Hebrew poet Chaim Nachman Bialik both studied and taught. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were about 200-khedorim left in Odessa, serving 5,000 mostly impoverished pupils.

In Odessa, the movement to assimilate into national Russian culture (though Jews were often denied the opportunity to assimilate into the local Russian culture) was particularly strong. Secular or nominally religious schools, whether Russian, Hebrew, or Yiddish, were quite attractive to the majority of Jews, even early in the community's history. In 1826, a secular public school was established to instruct young Jews in a combination of religious and modern methods, with considerably more emphasis on the latter. Subjects included Talmud, Hebrew, Russian, French, German, mathematics, science, and rhetoric. Ten years later a similar school was founded for girls, with the addition of needlework. Steadily increasing numbers of Jewish students enrolled in Russian schools of all varieties. Secular colleges teaching agriculture, arts, music, and liberal professions were also popular, as were vocational schools, most notably the well-known school of the Trud Society, which offered courses in mechanics, cabinetmaking, and ironwork among other subjects.

Great Leadership in Politics and Art

Press

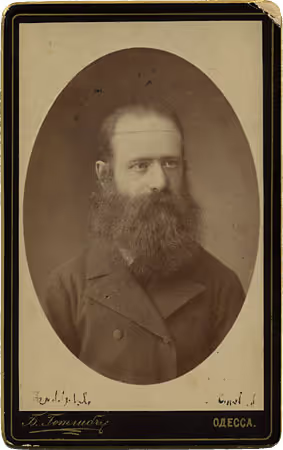

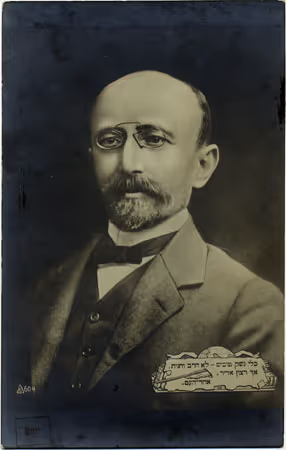

Naturally, the bullhorn through which Odessa's many political groups broadcast their views was the active Jewish press, a forum that was vocally anti-pogromist and adamant about Jewish defense. Russian-Jewish newspapers of the 1860s gave rise to a new, radicalized and militant tone. The first and foremost of these was Razsvet, a lively journal edited by the heroic Osip Rabinovich (1817-1869), in which he ceaselessly championed equal rights for Jews. Somewhat less bold, but also making use of a radical tone, were Ha-Melitz (The Advisor) published in Hebrew, and Kol Mevasser (The Announcer) which was published in Yiddish by secular movements of the 1860s. By the turn-of-the-century, as Zionism and a Jewish cultural revival gained profound momentum, the numbers of literary forums quickly rose, giving birth to the new publications Kavveret (Beehive), Pardes (Orchard), and Ha-Olam (The World).

Writers

Perhaps Odessa's greatest legacy to Jewish culture was its remarkable literary scene, featuring a list of major writers that reads like a "Who's Who" of the era's Jewish intellectuals: Saul Tchernichowsky, Isaac Babel, Simon Frug, David Frischmann, Moses Leib Lilienblum, Mendel Mokher Seforim, and Chaim Nachman Bialik, among many others. They wrote in Russian, Yiddish, Hebrew, and German; they passionately grappled with the issues of the day such as Jewish identity and emancipation, Zionism, Russian culture, and contemporary politics.

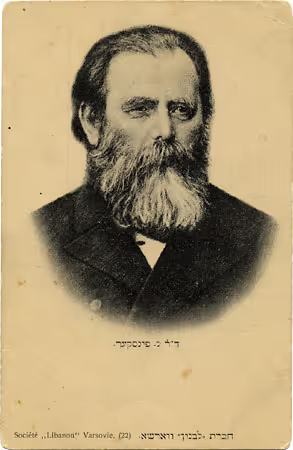

Among the most important authors who wrote in Hebrew and Yiddish, but eventually contributed to the great development of the Yiddish belle lettres, was Mendele Moikher Sforim (born Sholem Ya'akov Abramovitz, 1835-1917). Known as "Der Zeide" (the grandfather) of Yiddish literature, Sforim wrote pioneering novels in Yiddish - including Dos Vintshfingerl (The Magic Ring), Di Kliatshe (The Mare), and Dos Kleyne Mentshele (The Little Man) - beginning in the 1860s, when the Yiddish language was still considered by many to be a "dialect" unequal to Hebrew, German, or Russian. Reflecting afterwards on his early embrace of Yiddish, Mendele wrote:

"I tried to compose a story in simple Hebrew, ground in the spirit and life of our people at the time. At that time, then, my thinking went along these lines: Observing how my people live, I want to write stories for them in our sacred language, yet most do not understand the language. They speak Yiddish. What good does the writer's work and thought serve him, if they are of no use to his people? For whom was I working?"

One of Odessa's most celebrated Jewish authors, Isaac Babel (1894-1940, although not a Yiddish writer was among the first Jews to write in Russian.). He first became famous for his Odessa Stories in 1923, a widely popular work chronicling the crime and vice-ridden streets of Moldavanska, the Odessa Jewish slum. Three years later, Babel wrote Red Cavalry, a rare document recounting the 1920 Red Army campaign into Poland.

The Yiddish theater, which got its early start in religious plays performed during the holiday of Purim, came into its own in the 1870s, after the Romanian actor Yisroel Rosenberg brought it to Odessa. This inspired the great Abraham Goldfaden (1840-1906) to found a Yiddish theater. Goldfaden was a prolific poet, actor, and playwright who wrote more than 60 pieces ranging from satires and comedies to melodramas and biblical operettas. Among his most memorable works were Schmendrik (1877), The Fanatic(1880), and The Witch (1887). Goldfaden's plays, which were performed throughout the Ashkenazic world, helped spotlight Yiddish theater as an important part of Jewish popular art and entertainment.

Also working within the Odessa theater scene from the beginning was Jacob P. Adler (1855-1926), one of the most famous of all Yiddish actors. Born in Odessa during the mid-19th century, Adler did not truly make his name until he left the city in 1883 because of the czar's new ban on Yiddish theater. In London, Adler performed The Odessa Beggar and, gaining notoriety, soon emigrated to New York, where he became a huge star of the Jewish stage and established a family dynasty of Jewish theater.

.avif)