My First School Days

Introduction

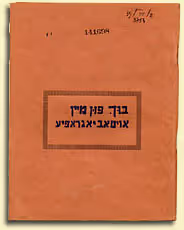

"G.W." wrote his autobiography in Yiddish in 1939, at the age of 20, as an entry in an essay contest sponsored by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. YIVO, then located in Vilna, Poland, invited young Polish Jews between the ages of 16 and 22 to write and send in their life stories.

I am sure that you will find my work very useful, although the language is perhaps not very good. But this isn't my fault, as I never attended a Yiddish school, and therefore my writing is full of mistakes - please take this into account. If you can, please send me some material that will teach me how to write Yiddish well. That would be a great thing for me to have, and I would be forever grateful to you.

My First School Days

G.W. spent part of his childhood in a very small town in the province of Lublin, a large city. Jews made up the majority of his town's population.

When I was three years old my mother took me to kheyder. To get to the melamed, who lived not far from us on Siedlecka Street, we went through a small passageway between two brick buildings, behind which were several very low, crooked, old houses surrounded by a wire fence.

We entered one of these houses. I stood on the doorstep with my head hung low, my finger in my mouth, angry, as if I somehow understood that I was being robbed of part of my childhood freedom.

The teacher was a short man with a long red beard. He wore a traditional Jewish cap and a long coat tied with a sash. The teacher called me over to the table, where about ten children were sitting, and introduced me to the first letters of the alef-beys. He told my mother to leave me at the kheyder, and she went home.

I sat there silently, looking around to see where I was. It was a small, low room. On the right, near the window, was a cot, and near that was the table where the children studied. On the other side was a long bench, and at the narrow side of the table was the teacher's chair. Opposite this, near the wall and in the very middle of the house, was a small chest with an iron band all around it. Near that was a door leading to an alcove. In the corner, opposite the door through which we entered, was the fireplace, which also served as a cooking stove.

It was nice and warm in there, and it reminded me of the song that my mother used to sing: "On the hearth, a fire burns, and it's hot in the house." The teacher recited a blessing with the children. I already knew it, because my mother had taught it to me, and I said it along with them. I went to this kheyder for two months and learned the alef-beys.

From the first day I went to kheyder I felt at home with the other children. We all played together, jumping up from the ground onto the top of the chest and back down again. On one of those jumps I smashed into the corner of the chest and cut my forehead, right in the middle. I started bleeding, and the teacher's wife applied cold water to my head. In the meantime the teacher sent for my mother, and I was taken to the feldsher, who stitched me up and bandaged me. It really hurt, and every day I went to be rebandaged.

I didn't go back to this kheyder anymore, and the cut left a permanent scar in the middle of my forehead. That's why this kheyder has remained so vivid in my memory.

After my head had healed my mother took me to another kheyder, with a better melamed, where I learned how to recite prayers. He was an older man with a gray beard, and he was very strict. He maintained authority with a leather whip that lay on the table. His face looked severe and angry, and all the children trembled at his glance. In addition, he had a particular practice of keeping delinquents after class.

We had lessons together twice a day: first, in the morning, and then, after he finished working with each one of us separately, we would have a second lesson together. This meant that we had to be in kheyder almost the entire day. But because we weren't used to this we would run outside, and for this the teacher often struck us with his whip.

Once, I got into a lot of trouble by talking a few children into going outside and, one by one, we sneaked out of the kheyder. We ran off somewhere far away to play. As usual, the teacher ran around looking for us and couldn't find us. When we returned later he gave each of us a beating and asked who had told us to run away. One of the children unintentionally let it slip that I had put them up to it, and the teacher punished me by keeping me after school.

It was a summer evening and already quite dark, and I had to sit there alone in the kheyder. I was getting very hungry, and the teacher still hadn't said I could go home. I started crying, and he came over to me and told me never to do that again, and then he let me go.

We Move to Wlodzimierz

G.W.'s father, a shoemaker, found it increasingly difficult to earn a living in their town. He and his partner Hershl went to the larger town of Wlodzimierz in search of business. When they were somewhat established there, they sent for their families.

At the end of 1925 we all left our home town together: my mother, my two little brothers, and I, with Hershl's wife and her two children.

It was freezing outside and a fine snow was falling. The wind was blowing fiercely. We all sat in the sleigh together. We children were covered with pillows, because we were still weak from the measles and could barely breathe. The train station was four kilometers away.

The coachman drove the horses quickly, and in an hour we were at the station in Niemojko. It was a small, low, wooden building, not far from the tracks. We raced inside the station to a big empty room with several long benches on the sides along the walls. Not far from the ticket window there was a warm stove. We ran over to it to warm ourselves. My mother and Hershl's wife went to the ticket window to buy tickets.

There was still half an hour until the train left and we sat and waited patiently. My mother's younger brother had come to the train station with us. He said goodbye to us and gave candies to all of us children. My mother and Hershl's wife bought the tickets and came back to wait with us. Many people stood at the ticket window buying tickets. The train whistle blew; it was coming. Soon it whistled again and stopped. My uncle helped us get on board. He said goodbye to all of us once more and dashed off the train.

Soon the train whistled again and moved. It was dark all around. It was nighttime; I looked out the window and saw nothing. We were moving. The other children and I went to sleep. My little brother slept in my mother's arms. I lay on a bench. In my sleep I imagined that I was with my father, and we were all laughing and happy together.

In the middle of the night we arrived in Brzesc nad Bugiem, where we had to switch to another train. We went into the station to wait. It was a large, beautiful station with many doors and rooms, brightly lit with electric lights. It was the first time I had ever seen them, and the brightness was blinding.

We waited for about a quarter of an hour until our train came. Taking all our belongings, we boarded the train, which went directly to Wlodzimierz. As we traveled it grew light. I sat and looked out the window, watching as we quickly passed through regions I had never seen before: snowy fields, villages, towns that couldn't be distinguished from each other.

Finally we arrived at the station in Kowel, where the train stopped for a quarter of an hour. From there it was only five more hours to Wlodzimierz. We traveled on, the train puffing hard, as if it were exhausted from the long journey that took almost a full day.

Because of my illness, I didn't start going to public school until I was eight years old. When the school year started after summer vacation, my father enrolled me in public school on Ostrowiecka Street.

To this day, the street where the school stands looks the same as it did years ago. Most of the people who live there are Christians. The school is a low, wooden building surrounded by gardens and trees. The air there is very healthy and pure.

Because of my illness I was a whole year behind for my age. I was both emotionally and physically too weak to take the entrance exam for the second grade. I had recently had diseases, such as the measles, which left me in a weakened condition, and then the lung ailment made things even worse. Although I was now attending school, I was still weak, and for the next three years I often suffered a relapse of my illness.

Now I'll get back to the school. The warm weather was soon over, and winter came. I dressed warmly and went to school every day throughout the winter with very few interruptions. Our teacher was a cheerful fellow, although he used to mumble. He used to teach all his classes in a sing-song, so we called him "the silent singer." He was a good man, very friendly, and his students would literally climb all over him.

I, however, was very quiet by nature, and for this reason the teacher liked me and had me sit on the bench closest to him. I did very well in school, as I'd already had some advance preparation, which made it easier. From my very first minute at school I showed great aptitude in painting and pasting--that is, arts and crafts. I put so much effort into everything I made that the teacher simply marveled at my work. I used to paint all sorts of birds and flowers and other things, too [...]

Winter passed and spring came. All around the school everything had turned green, and it looked so nice that it was simply a pleasure to go to school. For Constitution Day on 3 May, our teacher organized a choir of children in the upper grades, and they put on a very fine concert for the school. There were also some recitations, and at the end they performed a scene from a play. This was the first public performance I had ever seen, and I liked it very much.

The school year was at its end. There were eight days left to distribute exam papers and grades. There was a lot of commotion at school, and we weren't learning much because our teachers were busy with grading and writing reports. We played outside for hours at a time, happy because our two-month vacation was about to begin.

Report cards were handed out on 20 June. I got very good grades and ran home, happily looking forward to the vacation. At home, as always, I found my father working at his cobbler's bench and my mother preparing lunch. When I gave them the results of my first-grade report card--and especially when I told them that I had been promoted to the second grade--everyone in our house was happy. Even the younger children were happy, although they didn't really understand what was happening.

My father promised to have a new suit made for me, and he kept his word. In a few weeks he actually had suits made for me and my younger brother.

Then I went back to the TOZ summer camp for a month. We used to go at eight o'clock in the morning and stay until six in the evening. This enabled me to recuperate [...]

Middle-class and Poor Children

At school I came in contact with all kinds of children, both rich and poor. I could tell them apart by their appearance and dress. We used to study and play together; we spent time with each other and became friends.

In the lower grades the gap between rich and poor was very small. But as we got into the upper grades--say, fifth or sixth grade--there were fewer and fewer poor children. At the time, I looked at who my friends were and who attended school with me. At first I couldn't accept the idea that there was a divide between the working class and the middle class.

AT FIRST I couldn't accept the idea that there was a between the divide working class middle class and the middle class

The children of wealthy families and even of the lower middle class were more friendly with the other "big shots" than with us. When I was in the fifth grade there was still a group of eight to ten children from working-class homes, but by the sixth grade there were only three of us left, because the rest got left back in the fifth grade. Only then did I see clearly the line that divided me and my two friends, Yudl and Moyshe, from our other classmates.

What were the factors that deepened this rift? Very simply, my friend Yudl and I didn't have textbooks, and it was hard for us to learn. We studied together; he had one book and I had another one, but we didn't have any of the other books we needed. We tried to borrow them from our classmates, but our requests fell on deaf ears.

Yudl's father was a bookbinder, and we both studied in his workshop. He was a class-conscious worker. As he worked he would explain to us why something was the way it was or why it was different, and Yudl and I would stand there and listen. We began to understand what separated us from them.

The school year was over, and we were both left back in the sixth grade. I wasn't surprised that this happened. I didn't register to repeat the sixth grade, because even repeating the year would have interfered in my pursuit of a trade. So that was the end of my public school education.

When I was in the fourth and fifth grades I began to have aspirations for my future. I knew that there was such a thing as gymnasium, a more advanced school where you continued your studies, and that then you went to university and became an educated person--a doctor or a lawyer--and there were many other things to study as well.

It never occurred to me that I wouldn't study and realize my aspirations. My dream was so bright, so full of desire for something loftier, something grand and beautiful. In a word, I was filled with a great desire to become an educated person.

The turning point came unexpectedly. In the sixth grade I felt instinctively that this road was somehow closed for me. When I saw that I didn't always have enough money to buy a book or a notebook, I began to wonder why this was the case and what would happen in the future.

Gradually I became more resigned to my fate. Life's harsh realities put an end to my dream all at once. I was very upset when I finished the sixth grade with poor marks, even though I had been expecting this for a long time.

Now came the turning point in my young life. When I came home my father explained that I wouldn't be going to school any more and that I would start to learn a trade. I finally realized that higher education wasn't for me, that having to live on my father's income didn't afford me the possibility of going to school. I had to make peace with reality and abandon my dream.

G.W.'s family could not afford to send him to school past the 6th grade. When he was about 15, he went out into the workforce to earn his living.

Eventually, I decided to learn to become a tailor. After Passover, during my second year out of school, I entered a small tailor's workshop and started to learn the trade. I bought a thimble and some needles and sat poking at a scrap of cloth until I learned how to stitch. It was very hard for me at first, because I had to get used to sitting in one spot all day.

During the first weeks I was bored and tired. My shoulders felt as though they were breaking from sitting hunched over a needle thirteen hours a day, but I felt that I had to do this, that I had no alternative. Somehow, I persevered and got through this period.

My boss was a short, fat man. He was so stingy that he would save the basting threads and reuse them. Gradually, after I had become somewhat used to things, he had me do various odd jobs. He made me wash the floor of the workshop, and he would have me carry packages to his home. When it came to teaching me, he was no expert, so I decided to look for another workshop, and, after only two months, I left him.

After Tisha B'Av I entered another, larger shop, where they mostly made military clothes. There were four journeymen employed there, and I was the fifth employee [...]

The workshop was in a small room with one window hidden from the sun. There were two sewing machines, an ironing board, an upholstered couch, several chairs, and a narrow tailor's workbench. It was very crowded. In front of this room was a smaller kitchen, and beyond that was another large room, which served as both a dining room and a bedroom.

[...]At first, the work went quite well; as soon as I arrived they showed me how to do various kinds of hand work. They didn't use me to do any odd jobs, because the other workers didn't allow it. One of them was the shop steward; he was a class-conscious worker, so I felt quite good about the new shop.

The situation changed. His boss began to send him to do errands in the barracks of the regiments who had ordered uniforms from him instead of teaching him tailoring skills.

Sometimes I would remind my boss that time doesn't stand still and that I wasn't learning anything. He would brush me aside without a reply, telling me that he still had plenty of time and that eventually I would know something. I would tell my father all about this, and he quarreled with the boss several times. This had some effect, and after every argument with my father the boss would teach me something [...]

The three years were nearly over. Gradually, I had begun to master the trade, but this had happened only because the other workers went on strike over money that the boss owed them. As I was an apprentice and didn't get any wages, they didn't ask me to strike. The boss was angry with them and wanted to spite them, so he said that he would work just with me.

I took advantage of the opportunity, and he started to teach me how to do some things, giving me one piece of work after another. During the two weeks that the strike lasted I learned how to make many things, including a pair of trousers.

The boss still owed me seventy-five zloty, according to our contract. He didn't want to pay me, but I decided that I had to get the money, come what may. Seeing that our agreement was soon up, my father came and talked things over with the boss and his wife. Though she had to pay me, she screamed that she wouldn't. When they realized that they couldn't do anything about it and that I had the right to demand payment, she gradually paid me thirty zloty.

When my father went to demand the remaining forty-five zloty, they explained to him that he wouldn't get the money, and that if he forced them to pay through a union arbitrator, then the boss wouldn't sign my apprentice's certificate. The boss wasn't aware that the trade union office could force him to comply, but my father didn't want to go that far. He summoned the boss to appear before a union court, which ruled that he had to pay me what I was owed. He wrote out an IOU in court, because he had no choice; he had to pay what he owed me.

This was my only revenge. I used the money to have a new suit made.

I Join the Jewish Labor Bund

[...] For a long time I had been looking to become involved in an organization that represented my interests. When I was still in school I learned of the existence of these organizations, because many of my friends there belonged to various Zionist groups. Even then I wondered what these organizations were doing, as the people in them were always feuding.

When my friends invited me to join one of the four different Zionist groups that were around at the time, I replied that I didn't see eye-to-eye with organized movements that all strive toward the same goal and yet aren't united but are divided and fight among themselves. Therefore, I couldn't join them.

At the time it didn't even occur to me that there was an organization that was opposed to all forms of Zionism. Later I took night classes, where I met friends from my childhood who had become tailors or carpenters or were employed in other trades, and who had already joined Tsukunft, the Bund youth movement. They began to recruit me, informing me about the principles of socialism, and I realized that this was the cause that all workers must take up.

I hate how I have suffered, I hate the people who have exploited me

I decided that after I finished night school I would become a member of Tsukunft. I had started taking night courses before I began learning a trade. I finished the three levels of night school during the second year of my vocational training.

In fact, I joined the movement right away; it was still in its early days. Here I discovered a new life, a life full of belief in the future. It prompted me to think about describing the evil that I'd had to endure in the workshop, about denouncing everything that is dark and bleak, bloodthirsty and exploitative.

I thought that if I had someone to tell all this to, I would describe it and fix it in my memory forever. I hate how I have suffered, I hate the people who have exploited me; even now, when I think about them, I feel a surge of anger, and I can't forget--my hatred for them continues to grow.

The youth movement drew me in, and I became a part of it. I felt at home there. I started to understand my world and how best to live in it. I began to devote my free time to the organization and became an active member.

I started to think independently about everything around me, my material existence, my poor living conditions, both private and communal. I had to think about whether things had to stay the way they were or whether they might be different. I had to think about my station in life, which I had only partially attained, and about why I didn't even have the possibility of living better and enjoying life, nature, and everything created by humankind.

In today's hard times it's very difficult for me to find answers. One person lives at the expense of another, and that person lives at the expense of a third; the world trudges on in its crooked old way, and we can't attain our goals. This is why I had to start looking at life differently that I had previously.

[...]Young people live with hope and faith in a bright future. Those who are deeply convinced, believe. But there is a question as to when that day will come. When do we stop hoping? No one has determined this yet. I have set a limit, you might say, on my hope.

I think that the old ways will persist until the 1950s, certainly no longer. And then the day of true brotherhood among nations will come, the day of our ultimate belief in a completely classless society will approach, and people throughout the world will be free--they will be free.

What Became of G.W.?

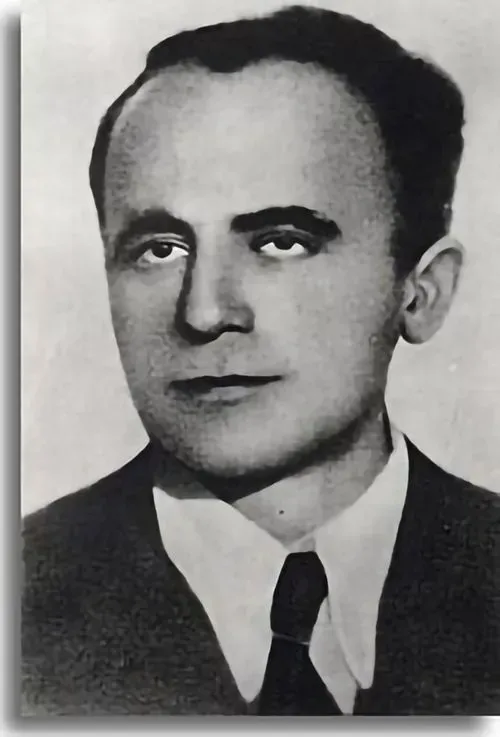

It is believed that G.W. perished during the Holocaust not many years after he wrote his autobiography. His death is listed in the memorial book of his home town, but no details about how he met his death are given.

.avif)