The Roots: Synagogue and texts

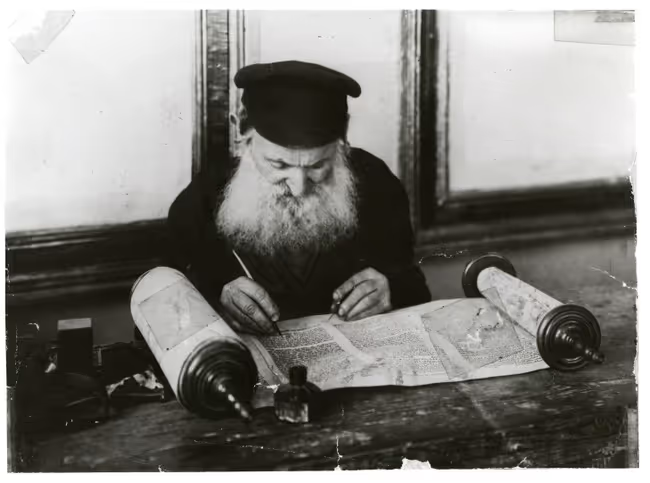

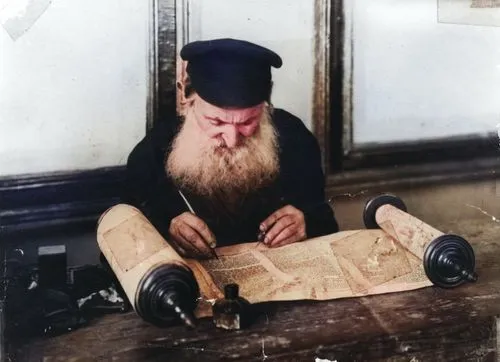

No matter where Jews settled throughout the world in the Diaspora, they brought with them virtually the same collection of essential religious objects and other ingredients, and the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe were no exception. They carried with them their sacred texts, which helped them interpret the world they were living in within the tradition's framework of laws and wisdom. They brought with them the Torah (Toyre in Yiddish), the five scrolls of biblical texts (what is also known as the Pentateuch), and Talmud texts, which provide rabbinical interpretations of the Torah and elaborate on its many laws. These texts, handwritten on parchment, were sacred commodities and a special scribe (soyfer) was in charge of reproducing them as well as the newer rabbinic commentaries that were being added. The scribe's activity has always been seen as a religious undertaking itself for which a scribe was required to train not just in the art of calligraphy - for a text's accuracy and artistic reproduction - but also to understand and revere the actual meaning of the words.

.avif)

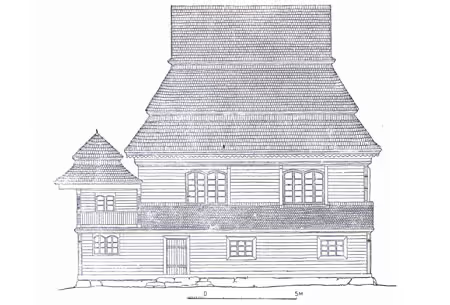

Equally important for Jews seeking to reproduce their culture and religious traditions in exile was the institution of the synagogue (shul in Yiddish), innovated by Jews to serve as a stand-in for the central Temple destroyed by Romans in Jerusalem in 70 CE. The synagogue, (a word of Greek origin, is known in Hebrew as a Bet Midrash (House of Learning), or Bet Knesset (House of Gathering) was an essential form of internal organization for Jews everywhere. The synagogue has always provided a social and communal context in which to explore and interpret the many intellectual themes and dictates of Judaism, as well as being a place to congregate, pray, and gather spiritual strength and emotional expression. The Jewish emphasis on learning, discussion, analysis, elaboration, and intricate intellectual dissection of ideas and religious texts were at home in the synagogue, and this mode of grappling with Jewish texts and Jewish ideas was extended to the yeshives, the special Jewish academies of formal religious learning created throughout the scholastic centers of the Diaspora.

Changes and Continuities

Although religious traditions are by definition quite static and ingrained in the minds of the group, Jewish religion and its traditions have also incorporated dynamic and adaptable possibilities. Try to picture yourself in the Eastern Europe of the early 19th century as you read this imaginary letter between two religious Jews as they confront the sweeping changes of the times:

Dear Friend,

I write to you after a silence of many years. Since your family left Poland in the days of our childhood, I have not laid eyes upon you, nor chosen to write to you of my life. Now, on the eve of my firstborn son's wedding, I want to break the silence, in the hope of learning of your fate in the Holy Land of Israel and for you to be able to share my joy. There is so much to tell, you would not recognize this place.

I wonder if you have had any news about our life here. Life has become significantly more complex and the community more divided since our childhood days. The Va'ad, which once was arbiter of all decisions of import in the Jewish community, and which was responsible for collecting taxes and settling disputes, is no longer. In 1764, the Polish government decided it had no use for the Va'ad, and since then, Jewish life has been torn in two by a great rift. Many different groups now want to lead our communities, and brother is divided against brother, father divided from son. The bitterness and anger felt by the opposing parties are great, and the leaders of the two groups, Hasidim and Mitnagdim, exchange angry words regularly.

Do you know about any of this? Did anyone describe this to you? The first great leader of the Hasidim was Israel ben Eliezer, a man known as the Baal Shem Tov (master of a good name). The Baal Shem Tov attracted many disciples in Poland and Lithuania, myself included. I was excited by his notion that God could more easily be found in joy than in suffering, and that the denial of earthly pleasures was no guarantee for Heaven. This rebbe had a tremendous, overwhelming personality, and many flocked to his table for words of wisdom each Shabes. At the shaleshudes (seuda shlishit in Hebrew), the third meal of Sabbath, we visited at his tish (table), which is when all his disciples gather around to hear the words of the wisdom of the great tzadik (righteous person). Knowing of his closeness to the higher realms, the other disciples and I rushed to his side, hoping to share some portion of the food he had touched. This tzadik was also there to help us with our other needs.

If we had a question, whether of spiritual doubt or just uncertainty, we could go to him, and he would gladly answer. Since most of us could not afford the luxury of staying by the tzadik's side constantly, because we have to earn a living for ourselves, we made sure to flock to him during the holidays, the times of greatest spiritual obligation. He has a few students that follow in his steps. I know that when people visit these tzadikim they bring a kvitl, a paper note on which one pours out all the difficulties of the moment. They submit it to the tzadik in the hope of receiving a blessing from him. Knowing of the tzadik's need to provide for his family as well, we accompany the kvitl with some money.

The Mitnagdim are now also organized as a group, and they want to sustain only older, traditional ways. They find the Hasidic rebbes and their followers to be anti-intellectual, anti-rational, promoting the "worship" of their leaders. In short, in the eyes of the Mitnagdim, we Hasidim are idolaters. They have burned our books, placed on us a herem (ban) and written works that dismiss us as charlatans. The most important leader of the Mitnagdim is the Gaon of Vilna, who is universally acclaimed as a great scholar, regardless of which side of the debate one is on. I imagine it will take more time for others to see us as good, loyal Jews, and to stop this rift growing between us.

Nonetheless, while much has changed, much has stayed the same. Whether Hasid or Mitnaged, study of Torah is still a central presence in all our lives. The Torah, the Talmud, and all our sacred books, must be studied. We all do a little but we are not really knowledgeable. Many of us are uneducated, and cannot engage in such study, but some congregate in Yeshives to learn. My son has a good head on his shoulders and is now a yeshive student. The family of the girl he is marrying will have to support him, since I can hardly do that. But we are lucky; we found such a family, and the rabbis in the yeshive recommended my son as a good scholar.

Wandering the world for so many years since the destruction of our Temple in Jerusalem, the study of the Torah has allowed us to be who we are - Jews - wherever we find ourselves. The Torah as always continues to define our lives in every way possible. As People of the Book, we and our rabbis spend our lives engaging with our holy books and learning from the many great scholars who have interpreted them. The Talmud and the Torah are ever-living, ever-growing. Each of these scholars and commentators has offered his own visions within the pages of the Talmud. Today, every page of the book looks like an ongoing dialogue between the generations.

In our yeshive we always hear quotes from at least three scholars, all treated as beacons of light in the darkness of exile. Their works are pored over and studied continuously. The first is the great Rashi, whose commentary encompassed all of the Torah and Talmud. His assistance in deciphering the complex language and metaphor of those two books, and in providing illuminating commentary throughout, lightens our burden considerably. Similarly, the Rambam, Moses Maimonides, guides us legally and philosophically. His Mishneh Torah is still the first text we open after the Torah, always, and we explore his clear and precise commentary that untangles many of the knots in the texts. And Rambam's Moreh Nevuchim (Guide to the Perplexed), while substantially more difficult to parse, is said to be a comfort to the spiritually troubled. Finally, Rabbi Joseph Caro, author of the Shulchan Aruch, is now talked about as the best organizer of the interpretations on our halakha, the prescribed behavior in every possible situation.

I, who cannot go to a yeshive stay in our town and spend a part of my day in the Beit midrash - Beis Medresh (Yiddish). It serves a variety of purposes: this is our local center of religious life, and also a place to find other Jews. Some learn there all day, but most come to fulfill the mitzvah of praying three times a day. We recite shacharit (the morning prayer) first thing in the morning, minchah in the afternoon, and ma'ariv at the end of the day, with a discussion between the last two. I only visit the great yeshive at the times when students from all around come and gather, attracted by the lure of the great scholars teaching here. But my son has the opportunity to live and study in the yeshive, and like the other yeshive students, he is supported by the local Jewish community, which provides them with room and board. There is then a great feeling of camaraderie and our "yeshiva bochers" (boys) can focus all their energies on study, knowing they do not need to concern themselves with their other worldly needs. But, listen! Our town now also has teachers, a baal tfile (a master of prayer), and a scribe, as well as a few learned shokhtim (ritual slaughterers). We also have a small group of learned and important people who help to settle our disputes. You remember Chimke, the shy one, he is today a tailor here, but people often feel unhappy and complain about his work. So they complain and he complains back! Our rabbis keep busy.

Today, as a grown man, I talk a lot to my children about mitzvot. I see it as my duty to pass on as much as I can of our religious principles, our basic rules of behavior. So, I have taken to sounding just as our parents did when we were younger: I mention prayers to my sons, I remind them never to touch non-kosher food, and I expect them to always observe Shabes. I sometimes have to press my younger boy to lay his tefillin, and have to remind him that he must behave if he wants to have his own tallis soon, just like the one that his older brother has. Last Shabes I started thinking about you. Did you marry off children in our Holy Land? How is your life there and what has your fate been since you left this land? As we sang the traditional Kaboles Shabes prayer welcoming the Sabbath and greeting it as a queen, I thought about how much I would love to welcome you to my home. Oh, I so would like to see you! Our Friday night dinner is our weekly festive meal, not that we have so much to eat, but it is the best we can put together, and we drink and sing along with it. I often bring home a traveler so that he should not be excluded from the joy of Shabes and I would love to open my home to you, too.

Yes, life here has not gotten any easier, but we survive. I think you would recognize our life here, and the same words we pray, the characters that walk our shtetl streets. Yes, you would recognize the rabbi, the rebbetzin, the doctor, the shoykhet, the dayan, the languages we use, some of the books we study. I guess this long chain of connection provides some comfort when we are weak, some warmth when cold, and some support for our people. But, would you recognize me with my graying hair? I would like to visit you or accept a visit from you… but who knows?! One day, perhaps in the lifetime of my children or grandchildren, they may be blessed with the opportunity to return to the Holy Land… Until then, I hope that the Torah glows as brightly in Safed and Tiberias as it does here in Poland...

Your friend and brother,

The Politics of Religion

![New Year's greeting card with a Reform Jew wishing an Orthodox man a happy new year in Yiddish: "Daytsh [Reform] or Hasid, rich or poor/ Press hands, brothers!/ Happy New Year/ Whoever or whatever you are!" (Poland, date unknown).](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6891ffac7571e63c0e0f2860/6891ffac7571e63c0e0f2af9_15_l_postcard_lg.avif)

As the 18th century arrived, the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, opened up the Jewish people to the possibilities of the larger world outside their community, while drawing many of them away from the faith of their ancestors. The Haskalah attracted many Jewish intellectuals to the realm of rational thought and liberal ideology, privileging secular society against what was defined as insulated parochialism. Changes in Jewish observance and for some even assimilation, often appeared as parts of ideologies and were perceived as a threat by the more religiously minded Jews. Putting aside many of their bitter disputes, Hasidim and Mitnagdim joined forces in hopes of halting this new turn away from traditional Judaism.

The religious authorities that controlled and helped determine communal Jewish living arrangements would find many challenges to their views of Judaism, as new political movements and ideologies drew many from the ranks of the observant. Various novel political movements attracted Jews, from the Bund, the Jewish Socialist worker's organization that was active on behalf of the Jewish working class, to Zionists of many shades who looked to return to their homeland, Israel (then Palestine).

Understanding that the best way to compete with the new spate of secular movements was to form a party of their own, religious Jews founded their first political party called Agudas Israel--Isroel-Yisroel in 1912. It became a refuge for religious Jews attempting to stop the groundswell of secularization and maintain some authority within the Jewish community. Agudas Yisroel attempted to reach these goals in a concerted effort in Eastern and Central European countries to protect the observant Jewish way of life. This way of life was thought by them to be the best for Jews, and its practices important to maintain for all Orthodox Jews. Yet other Jewish groups mixing ideas and ideologies also sprang up-from Mizrachi, the modern Relgious Zionist party, to other non-religious political parties. Before World War I, religious Judaism had entered the fray of secular politics, at times modernizing itself and attempting to sustain its leaders as the main authorities of the Jewish community. However, 20th century Jewish life had too many competing leaders for one group to claim sole representation of the Jewish people.

About the Jewish Calendar : Holidays

The Jewish calendar is a guiding structure for Jewish life. It evokes and informs the rhythms of Jewish historical memory, thought and traditions. Holidays embody and represent important Jewish history and cultural moments and messages. Each has its own folklore expressed in food, music, and traditions. Each holiday is different in its content, its expression, in its prayers and even in the melodies sung during the festivities. The specific foods associated with a commemoration are evocative of the history behind the holiday, as is the oil used in Chanukah latkes (potato pancakes), or have secondary associations that are conjoined tradition, such as the use of the esrog (lemon) for the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot) that occurs at the time of harvest. An enormous variety of experiences and ideas are evoked by Jewish holidays, and these need to be explored.

Here is a sample of some of the traditions surrounding a few major Jewish Holidays:

Purim: The holiday commemorating the saving of the Jews in Persia from potential destruction, is a time when Jews read the megillah of Esther, a text written on a scroll that tells the story and reasons for the celebration. While much anger is evoked by the name of Haman during the reading (he was the potential destroyer of the Jews), and gragers (rattles) or foot stomping mark his memory, the day is a celebration! In a playful mode, Yiddish children's songs like "Yakhne-Dvoshe fort in shtot" (Yakhne-Dvoshe goes to town) were sung as youngsters ran and visited each other, ate homentashn (specially shaped poppy seed cookies), and dressed up as the historical characters of the story. The joyous atmosphere also affected the more contained adult world as well, producing carnival-like expressions of gaiety.

Passover: The special Seder meal is structured around the reading of the Haggadah, a liturgical text that retells the biblical story of the Israelites gaining freedom from Egypt. Various melodies are used for the recitation of the Haggadah story, and many of its songs are well known: Dayyenu ("It would have been enough"), Chad Gadya ("An only kid"), and piyyutim (poems) like Ma Nishtanah, which explain why the Seder night is different from all other nights of the year. Each of these pieces together make the holiday unique. The text read at the family table offers an opportunity for dialogue between the generations, for analysis and for education. The content is rich for the Passover holiday; there are many rules and regulations pertaining to food and household activity, as well as many varied traditions that make the week of the holiday a whole family experience, one that connects people not just to the historical messages, but to a variety of ongoing group traditions, including music and games, that foster ethical and philosophical explorations within the family.

Rosh Hashanah: The holiday marking the New Year and the beginning of the Jewish calendar is also the holiday during which each person begins an introspective assessment of his or her own actions and behavior. This is a time for a new beginning for each Jew. The Rosh Hashanah liturgical prayers said in the synagogue are familiar and recognized by the whole Jewish world. Perhaps it is the shofar (the hollowed ram's horn) that is the most specific and familiar musical instrument of this holiday. The custom is to blow it 100 times on each day of Rosh Hashanah. The person who blows the shofar is known as the ba'al Tokeah.

The shofar is intended as a reminder of Abraham's courageous willingness to sacrifice Isaac, his only son, in the famous Torah passage known in Yiddish as the akeyde (the binding), as well as a reminder of the creation of the world. Moreover , blowing the shofar serves as a reminder that a parent need never again sacrifice a child to prove faith. At the moment that Abraham was set to slaughter his son, in what was at the time an extreme but acceptable behavior within many cultures (i.e., Iphigenia in Greek mythology), an angel descended from heaven and told Abraham to cease, that God no longer demanded this immense sacrifice. At that moment, a ram appeared entangled in the bushes nearby and Abraham substituted it as the offering he had come to make.

Each holiday is infused with historical content to which it gives expression, with specific folklore, food, and music associated with the festivities. A world of messages and meanings spring up from similar explorations into other Jewish holidays; all share an underlying theme of striving for individual ethical growth and responsibility, and of God's love for the Jewish people.

.avif)

.avif)