Jewish Music in Eastern Europe

Music played a central role in Jewish life in Eastern Europe. As in Jewish communities worldwide, East European Jews continued the ancient musical traditions connected with synagogue prayer and public reading from the Torah. To this were added more recent religious songs for Shabes and holidays, based on medieval texts and melodies. Yet at the same time as they preserved their musical past, the Jews of Eastern Europe also actively created completely new kinds of Jewish music. The Hasidic movement that sprang to life in 18th-century Eastern Europe transformed Jewish society worldwide through its thousands of new, soulful, wordless melodies known as nigunim. Outside of the synagogue, Yiddish folk songs began to appear as part of all sorts of life situations, ranging from beautiful songs of romance and love, to children's lullabies, to epic ballads about famous historical events. Communal celebration was also a major theme and inspired creation of new styles of Jewish music in Eastern Europe. Jewish professional musicians developed klezmer music, an original style of folk music that transformed weddings in Eastern Europe into all-night dance parties. The holiday of Purim emerged as an occasion for elaborate musical plays poking fun at the leaders of the community, a custom which later evolved into the secular Yiddish theater. Modern times also spawned other innovation in Jewish music, including songs and anthems for political causes and groups such as the Zionist youth movement and the Bund; Russian Jewish classical music; and Holocaust-era songs of resistance and remembrance. In more recent times, many of the great East European Jewish musical traditions have gained a renewed and even expanded popularity, as contemporary Yiddish music finds enthusiasts among Jews and non-Jews around the world.

Prayer

The Jews of Eastern Europe inherited a rich tradition of religious (or liturgical) music stretching back to its earliest roots in the Bible. Religious music varied enormously in terms of form and function. In the synagogue, Jewish prayer was centered on ancient texts, which were mostly sung in a melodic chant. Musically, this was a collection of free-flowing melodies without fixed rhythm called the nusakh.

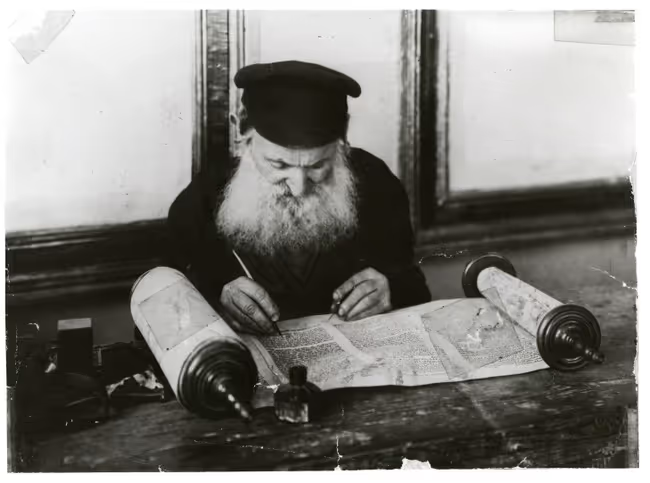

During the regular Shabes reading from the Torah, and on holidays, a special set of short and distinctive traditional melodies called Trope was used. Torah melodies were handed down from ancient times, and like the texts of the prayers, they were meant to remain constant and unchanged throughout the centuries.

Many sections of the liturgy were chanted or sung by individuals, and others chanted together by the entire congregation. While the texts of Jewish prayers were preserved through written prayer books, the music was part of an oral tradition, passed on from place to place, and generation to generation, by the informal prayerleaders who ran the services. Eventually, among Ashkenazi Jewry, there developed a specific occupational role connected to synagogue music and singing: the hazzan or cantor.

Beside the ancient prayers and Torah readings, there was always a large space left in the service for religious songs. These songs, called piyyutim were really religious poems, written in Hebrew and Aramaic, sung to a whole range of melodies, some old, some newly composed, and some adopted and adapted from neighboring cultures' folk songs. Piyyutim first appeared in the synagogue service around the 7th century C.E. Over time, some piyyutim proved to be so popular that they became permanent parts of the synagogue prayers. This was particularly true of the compositions of famous medieval Hebrew poets.

By late medieval times, piyyutim had begun to change in both form and function. They began to appear in other settings than the synagogue in East European Jewish communities, in particular at family religious celebrations such as the Shabes table and on other holidays. In addition, a variety of people began to compose and perform them. The most powerful piyyutim were often written by anonymous pious Jews. These include the unique tekhines composed by Jewish women in Eastern Europe, which are some of the oldest and most powerful examples of spiritual writing by women.

Shabes

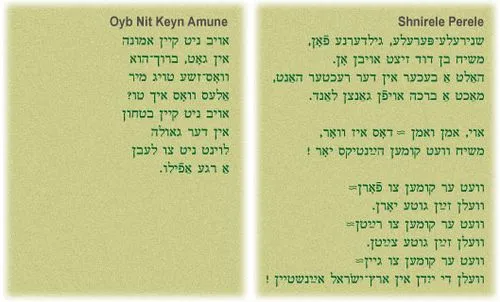

The Shabes (Shabbat, in Hebrew) table was one of the most musical places in Jewish Eastern Europe. Jews had already begun to write specific piyyutim for Shabes in ancient times. By the Middle Ages the custom had evolved to sing certain songs at each one of the three meals of Shabes (Friday night, Saturday midday, and Saturday early evening). These songs were called zmirot. A typical Friday night meal might include the singing of Sholem Aleykhem, from 17th-century Prague, Tzur Mishelo, attributed to the 2nd-century mystic, Shimon bar Yochai of Palestine, and Dror Yikra, composed by the poet Dunash ibn Labrat in 10th-century Baghdad. Most zmirot had Hebrew lyrics, but Yiddish was often used as well, as in the songs Oyb Nisht Keyn Emune and Shnirele Perele. There are thousands of different melodies for zmirot; some individual songs have hundreds of melodies. Although the words do not change, the melodies range from East European Hasidic tunes, to American pop, to those of Israeli folk songs.

Sholem Aleykhem is the best-known and universally performed Sabbath zemer (song). It is the custom is to sing it in the home right before the kiddush (kidesh, in Yiddish), a Shabes blessing chanted over a cup of wine that marks the beginning of the meal. The title literally means "Peace be on you", a common Yiddish greeting derived from the Talmud that is still used in various forms in nearly all Jewish communities around the world. The oldest version of this we have today is part of a collection of mystical prayers from early 17th-century Prague. The text retells a story from the Talmud, which describes how two angels, one good and one bad, escort every Jew back home from the synagogue on the Sabbath evening. The Jew blesses the angels, welcoming them into his home for the Sabbath. If the Sabbath table is well prepared, and there is a happy holiday atmosphere, the good angel blesses the Jew, promising another Sabbath just as sweet and good. The evil angel is forced to respond, "So be it". If this is not the case, the bad angel curses the Jew, "May you have just such another Sabbath", and the good angel is forced to respond, "So be it". The four stanzas of the song speak directly to the angels in the form of welcome greetings.

Jewish Professional Musicians

One of the major musical developments among Ashkenazi Jewry was the emergence of professional Jewish musicians who had well-defined, specific roles exclusively as musicians. A new development in the Jewish world, this had not really been the case since the time of the Temple. Nowhere else in the Jewish world did these types of musical professionals exist in such well-defined and particular roles.

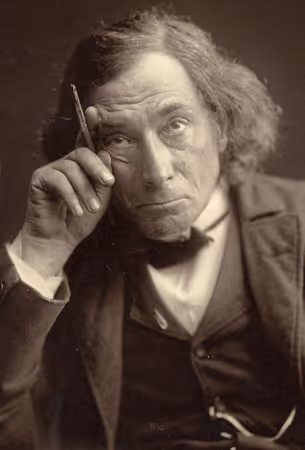

Jews have always turned to talented singers to lead the synagogue prayers and to sing special solo selections. In Eastern (and Central) Europe, the position of prayer leader and religious singer grew to be a full-time and very important profession called the hazzan (cantor). Cantors were considered to be important religious functionaries, though they did not have the same intellectual and religious authority or training as the rabbis. Their primary job was (and is) to lead the synagogue singing, to perform certain portions of liturgy on behalf of the congregation, and to religiously inspire the community with music.

Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, cantorial music developed from simple prayer chants and piyyutim into elaborate artistic compositions, in some instances almost like a Jewish religious version of European classical music. In the 19th century, as the Reform movement and the haskalah began to change the structure and nature of synagogue worship, for some congregations the role and influence of the cantor in Ashkenazi synagogues grew. Some cantors began to perform, accompanied by choirs of young Jewish boys known as meyshorim, who would travel and study with the cantors as apprentices. By the end of the 19th century, certain cantors had become famous throughout Europe for their unique and impressive artistic styles. It was not uncommon for the most celebrated cantors to be treated as international celebrities; many even performed in secular settings such as concert halls and also made commercial recordings.

Outside of the synagogue, the other principal type of Jewish professional musician to emerge in Eastern Europe was the klezmer musician. During the late Middle Ages, Jews became professional musicians in many other parts of the world, serving as official court musicians for Islamic royal dynasties in Central Asia and the Middle East, and even for Christian rulers in Italy. But only in Eastern Europe did Jewish professional musicians develop a totally new, distinctively Jewish, kind of instrumental folk music, which later came to be called klezmer music. The biblical term "klezmer" originally only referred to musical instruments or to musicians who played those instruments. Jewish instrumental musicians had existed since the 15th century in Central and Eastern Europe. Klezmer music was a unique cultural blend of Jewish and non-Jewish musical elements, which included synagogue melodies, Hasidic nigunim, medieval German folk dance forms, and modern Greek and Turkish dance music. All of these elements were combined into a new, innovative and completely Jewish style of instrumental music.

Klezmer music was most commonly played at weddings in Eastern Europe, where it accompanied both the solemn moments of the religious ceremony and the wild, happy dancing of the party afterwards. A typical early 19th century klezmer band included several fiddles, a cimbalom (hammered dulcimer), and a bass. During the course of the 19th century more instruments were added, including the clarinet, horns, drum, accordion, and even the piano. The musicians were almost always joined by the badkhn, a combination of a wedding jester, comedian, and emcee, who performed both serious and comic sermons, toasts, jokes, and stunts during the course of the wedding festivities.

Hasidic Music

One reason for the rapid growth and popularity of the Hasidic movement in Eastern Europe was its passionate belief that music itself was as vital and significant a way to pray as reciting the words in the prayer book. This emphasis on music and also dance as means to enhance spirituality and connect in a deep mystical way with God, led to the idea of the nigun, a wordless melody that is also a musical prayer. The nigun (melody, in Hebrew) was intended to transport its singers and listeners beyond the mundane worries of the world and into the realm of the spirit. A nigun was repeated over and over again until a sort of mystical harmony was achieved. In Eastern Europe, each Hasidic dynasty developed its own special styles of nigunim. Among the most admired were the Modzhitzer Hasidim, whose leader, Reb Yisroel of Modzhitz, wrote hundreds of nigunim. Some people also considered him to be a great artistic composer in the classical music sense.

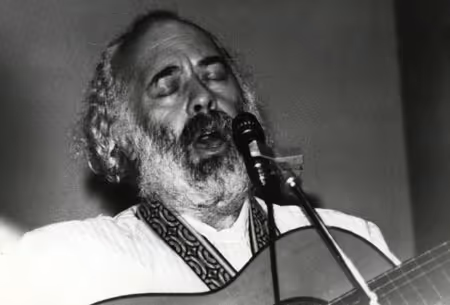

The tradition of the nigun continues today, both inside and outside of the Hasidic world. In postwar America, the talented composer Shlomo Carlebach created a whole style of Jewish music virtually by himself, using some traditional Hasidic musical elements combined with American popular music, to create a neo-Hasidic style that has proven popular around the world and in Reform, Conservative and Orthodox Jewish communities.

All Hasidic music was not strictly without words. Many Hasidic religious folk songs also appeared, with Yiddish and Hebrew lyrics, and sometimes both in combination. Some Hasidic songs even borrowed melodies and lyrics from Russian, Belorussian, Hungarian, and Ukrainian folk songs, adding Hebrew or Yiddish lyrics to turn the secular, non-Jewish songs, into a holy Jewish musical expression.

Yiddish Folk Songs

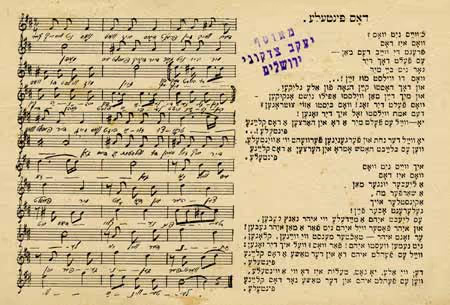

Yiddish folk songs began to appear in Eastern Europe not long after the Yiddish language itself. The medieval Yiddish folk songs that have survived are really long ballads, usually retelling epic stories of plagues, famines, and other dramatic historical events. Later Yiddish folk songs embraced a wider range of topics and featured everyday human emotions: young women's love songs, mothers' lullabies, children's play songs, men's drinking songs, and so on.

Some kinds of folk songs were sung by individuals, while others were intended for group singing or even to accompany young people's dancing. Songs were rarely written down or printed, although there were definite exceptions. The melodies of Yiddish folk songs came from a variety of sources, ranging from traditional synagogue motifs, to East European non-Jewish folk tunes, to European classical music.

Another important source of melodies for Yiddish folk songs was Jewish klezmer music; it was not uncommon for the same melody to be played as a klezmer tune without words for folk dancing, and also to be sung with words as a folk song .

In general, Yiddish folk songs were passed on orally until the mid-19th century. Modern collections of Yiddish popular songs written by individual poets and composers then began to appear in print. These Yiddish popular songs eventually merged with the modern Yiddish theater, which once flourished in cities around the world. Much of this music was disseminated and distributed through the modern Yiddish recording industry, which produced hundreds of commercial recordings of Yiddish music, particularly in New York City, from the 1910s through the 1940s. Some Yiddish popular songs even crossed over into the American cultural mainstream. One example of a successful crossover is the 1932 American Yiddish theater song, Bay Mir Bistu Sheyn (For Me, You Are Beautiful). It quickly went on to become a national favorite in both the United States (in an English version) and in the Soviet Union (in a Russian version).

Yiddish Theater

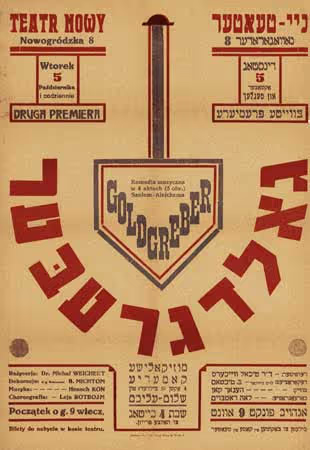

Jews in Eastern Europe began to put on improvised folk plays for the holiday of Purim as early as the Middle Ages, taking advantage of the holiday's built-in emphasis on costumes, celebration, and play-acting. In many communities, these plays evolved into elaborate folk theater productions with musical scores performed by singers and klezmer musicians. Then in the late 19th century, modern Yiddish theater began to emerge in Yiddish-speaking communities - from small towns in Romania to big cities like London, St. Petersburg, and New York. Music became a central part of this new theater, as playwrights and composers created fresh styles of popular songs and light operettas, borrowing liberally from all the other traditional kinds of Jewish music. The earliest plays, however, were performed as traveling street and cabaret theater, frequently without instrumental accompaniment.

Soon the Yiddish theater began to use pit orchestras of musicians, often recruited from the ranks of klezmer musicians, to perform long scores complete with overtures and solos. In the 1910s and 1920s, Yiddish theater flourished and became a huge musical industry in cities such as New York and Warsaw. Oddly enough, in its early years, the Soviet Union actually sponsored an official state Yiddish theater; this cultural experiment ended disastrously under Stalin's brutal repression of Jewish culture. Today it is still possible to regularly see Yiddish theater performed in New York, and Montreal, and occasionally elsewhere.

Russian Jewish Classical Music

As nationalism began to rise in late 19th-century Eastern Europe, many classical musicians across the region responded by turning to their people's folk culture as a source of artistic inspiration and material for their own compositions. A similar movement also began among Jewish classical musicians in Tsarist Russia, as young composers who had been classically trained in European conservatories began to focus their attention and efforts on Jewish music . By 1908, the St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music, a new musical organization, had been established in Russia. This society sponsored research to collect traditional Jewish music for scholarly study, popular education, and as the basis for building a modern Jewish style of classical music. Using elements from the full range of Jewish music - from Yiddish folk songs to Hebrew synagogal chants, to Hasidic nigunim, to klezmer dance tunes - these composers wrote chamber music, symphonies, concertos, and even operas . Although the society formally disbanded just 10 years later during the chaos of the Russian Revolution, the music created as well as its individual members have both proven to have a huge influence throughout the Jewish and general classical music worlds, especially in the former Soviet Union, Europe, Israel, and the United States.

Songs and Anthems for Political Causes

Eastern Europe was the birthplace of modern Jewish politics, and right from the start music played a significant role. Jewish labor activists and socialists used Yiddish songs to express their grievances and to recruit their fellow workers to their causes. Some of these songs were simply traditional Yiddish folksongs with new lyrics attached, while others used melodies from the popular marches and revolutionary songs of other Central and East European political movements. At political rallies, huge crowds of Jewish workers sang these songs together, often with brass bands accompanying them. Before World War I, workers' choruses also began to appear in Jewish urban centers across the globe.

The two most famous Jewish political anthems to emerge from Eastern Europe are the Zionist hymn Hatikvah ("The Hope") and the Bundist song, Di Shvue ("The Oath"). The Hebrew lyrics to Hatikvah were written in 1878 by Naphtali Hertz Imber, a Bohemian-born poet. The source of the song's melody has long been a point of controversy. Many have claimed it was based on a Moldavian folksong, while others suggested it comes from a symphony by the Czech composer, Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884). Still others maintain it is based on an old Sephardic religious melody. Whatever its true melodic source, Hatikvah became an instant favorite of the Zionist movement, and went on to become the national anthem of the State of Israel. Di Shvue was penned in 1902 by S. An-ski (Shlomo Zanvil Rapoport), the Russian Jewish writer. This Yiddish song, whose melody source also is unknown, exhorts Jews to unite, and to commit themselves body and soul to the defeat of the Russian Tsar and of capitalism.

Holocaust-Era Songs

During the dark days of the Holocaust, music was even more important to the Jews of Eastern Europe. For those Jews imprisoned in ghettos and concentration camps, singing Yiddish songs (both the newly composed and the popular prewar songs), was an essential element in maintaining psychological resistance and pride , as well functioning as a means of fostering some hope and happiness. Jewish partisan fighters wrote and sang songs to fortify their courage, and to celebrate "their victories" against the Nazis. These Holocaust-era songs are sad but moving testimonies to the deep soul, courage and determination of East European Jews throughout those times. After the war, these Yiddish songs remained as powerful symbols and memorials used for remembrance by Jews around the world. Many of these songs retain their powerful significance as anthems of the darkest period of Jewish history.

Contemporary Yiddish music

The musical traditions of Jewish Eastern Europe had already begun to decline in the late 19th century, due to emigration, industrialization, and acculturation. The tremendous destruction that accompanied World War I further displaced and eroded many portions of Yiddish life and culture, including the music. Moreover, during and after World War II, the devastation left by Nazi genocide against the Jews and the terrible postwar political repression in the Stalinist Soviet Union effectively crushed much of the remaining Jewish music and musicians in Eastern Europe. Yet beginning in the early 1970s, a new generation of young American Jewish musicians and scholars began to look beyond the Holocaust in search of the lost world of Yiddish culture. This huge renewal of interest in klezmer music and Yiddish folk songs, which began in the United States, quickly spread to Europe and beyond.

Cultural activists, academics and artists joined together to bring to light old recordings made before and after World War I in New York, Budapest, Kiev and other cities. Old and forgotten musical manuscripts have been recovered and republished. Jewish musicians, both those who had emigrated to the United States several decades earlier, as well as the more recent arrivals in the waves of Soviet Jewish immigration during the late 1970s and 1980s, were interviewed in great depth, and their songs and biographies carefully recorded. The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research was a leading focal point for many of these intellectual efforts. In the mid-1980s YIVO began to sponsor annual retreats where musicians and other Yiddish enthusiasts gathered to teach each other, perform together, and dance to klezmer and other kinds of Yiddish music. Since that time, the popularity of Yiddish music has continued its tremendous growth among Jewish communities in North America, Europe, and the countries of the Former Soviet Union. More surprisingly, a huge non-Jewish audience has developed for this music in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, especially in Germany, the Netherlands, and Poland; the popularity of Yiddish music has continued to grow even in locations where few Jews have lived since the Holocaust.

Today's musicians employ a variety of creative approaches to traditional Yiddish music. Some artists focus on preserving older traditional styles of klezmer and Yiddish folk song through their performance and teaching. Others, like Israeli singer/songwriter Chava Alberstein, have extended these traditions by composing new Yiddish-language songs. Still others are engaging in wild new experiments in mixing Yiddish music with other contemporary kinds of music, such as jazz, rock, reggae, ska, and hip hop.

.avif)

.avif)