Shtot

.avif)

The City

Because of the relative newness of medieval Eastern European cities, Jews and other outsiders had ample opportunity to make an impact on urban economies; Jews were also likely to form large minorities early on in many city's development.

The typical medieval Polish city was founded between the 13th and 17th centuries and resembled older German cities further west: built along a major river for ease of transportation and water supply, with the town forming around a major castle housing the royal representative or local feudal lord. Most cities were walled-in, with a central market square, cathedral, shops, clusters of houses, and crooked streets paved in stone. If the town was royal, municipal buildings also graced its streets and defined its character.

In pre-industrial times, Jews were severely restricted to specific quarters of cities, often barred outright from living (or working) inside the city walls. Jews were then compelled to seek the fickle protection of enterprising nobles in the hinterlands - nobles delighted to profit from Jewish industry, rent, and taxation. In more recent times, segregation was still a fact of city life, but it had grown to be enforced less by official law than by unspoken covenant. By choice or by default, Jews congregated within Jewish areas. Once the technology of streetcars and railroads arrived in the 1800s, Jews (and non-Jews, of course) had a good deal more choice of where to live and work.

Jewish settlers entered a broad array of occupations, necessarily depending on restrictions enacted against them: had non-Jewish guilds - fearing competition - forced Jews out of the trades? Arriving as merchants and financial middlemen, Jews branched out considerably as they staked claims to cities and marketplaces: crafts and trades (builders, tailors, smiths, brewers, bakers), professions (doctors, lawyers, engineers), and so on.

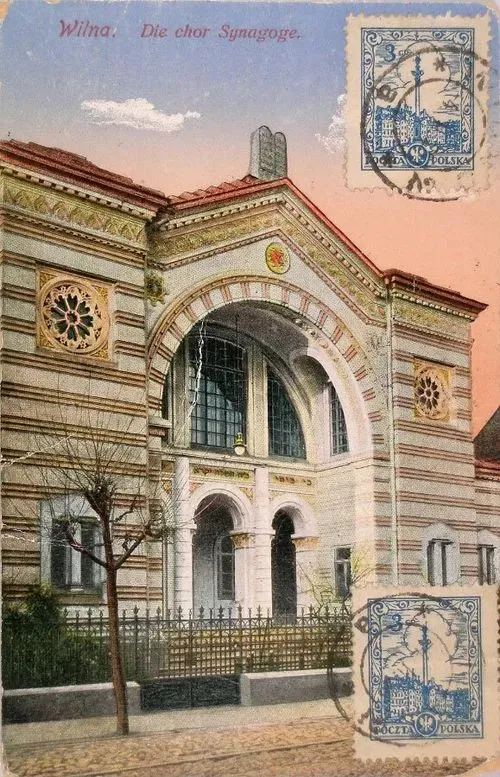

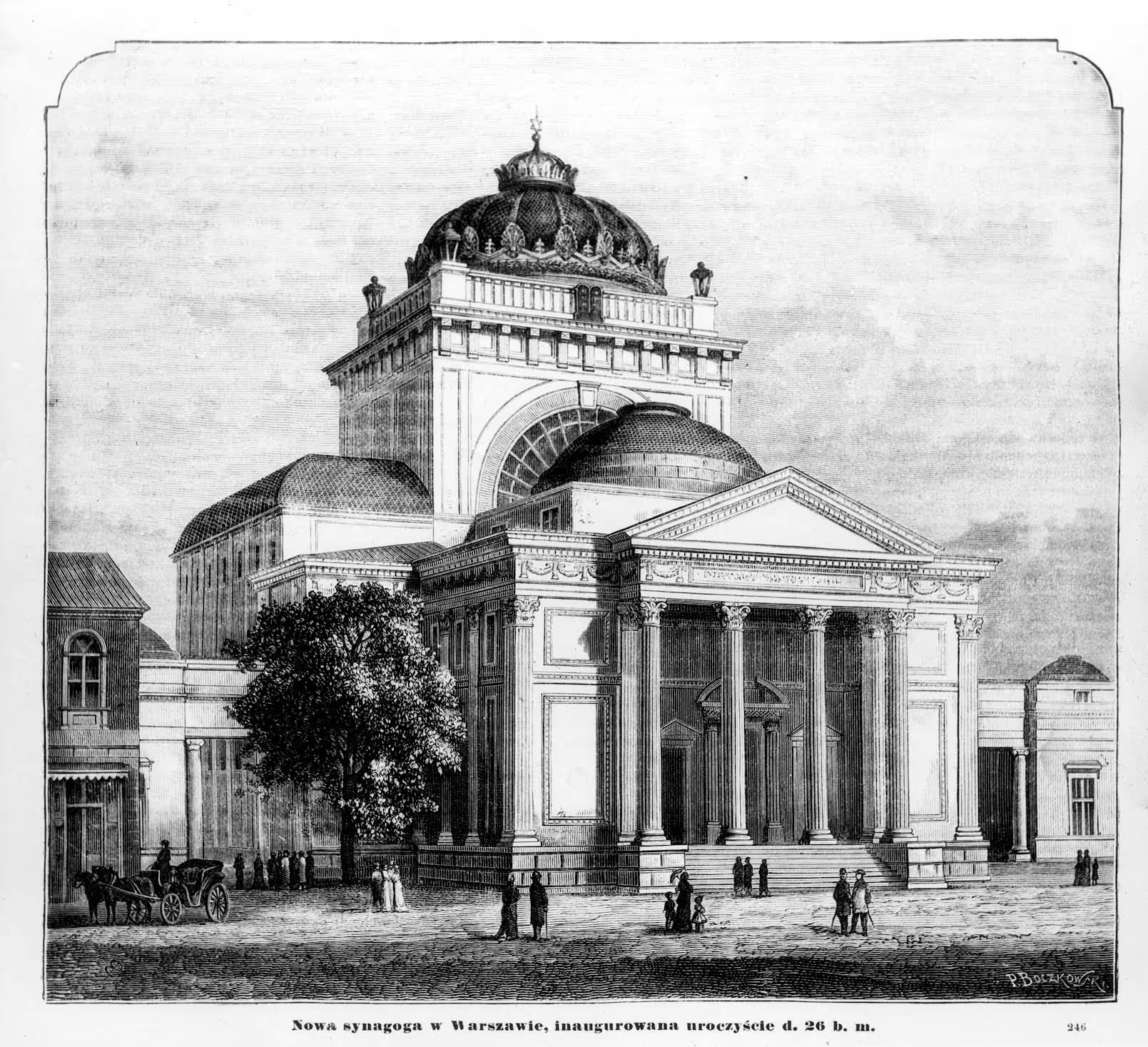

And, in each city, as Jews gained a foothold and some level of economic stability, community-leaders gathered resources to establish a familiar network of Jewish institutions: cemetery, synagogue, Mikvah (ritual bath), schools: khedorim for children, yeshivot (schools) for selected, older students, later on, after secular education developed at the turn of the 20th century, gymnasiums (high schools), and a kehillah (communal government, that encompassed welfare organizations of different types). With a true, healthy minyan - a quorum of people - urban Jews were able to construct these many private organizations and sustain them through the levying of taxes by the able families. This amounted to a doubly-taxed existence but was absolutely necessary for the sake of cultural survival. Each physical institution embodied that sense of increasing permanence and prestige: from wooden to stone synagogues; from Talmud-Toyres (religious primary schools) in cramped storefront quarters to spacious school buildings of their own. With the growth of actual institutions and concrete manifestations of the culture, the effervescence of Jewish life permeated the streets of the town.

Nevertheless, those institutions and, in fact, that mode of Jewish life encountered enormous challenges in the 19th century. The industrialization of Europe proved to be a major turning point for shtot and shtetl alike, with a massive overhaul of the way people lived, worked, and organized themselves. Economic woes, over-crowding, and social dislocation led millions of Jews, beginning in the late-19th century, to migrate to larger cities, leaving the older spread out shtetlakh for the more promising cities. Many even opted to leave Eastern Europe altogether in favor of burgeoning Jewish immigrant communities in the United States, Latin America, and Palestine.

די שטאָט

אַזוי ווי די נײַע מיזרח־אייראָפּעיִשע שטעט זענען אויפֿגעקומען אין מיטל־עלטער האָבן ייִדן און אַנדערע נײַ־געקומענע וואָס האָבן מיטגעאַרבעט בײַם בויען זיי געהאַט אַ שטאַרקע השפּעה אויף דער שטאָטישער עקאָנאָמיע; מער ווי אַנדערע זענען ייִדן געוואָרן גרויסע מינאָריטעטן אין שטעט וואָס האָבן זיך געהאַלטן אין אַנטוויקלען. אַ טיפּישע נײַע פּוילישע שטאָט וואָס איז געשאַפֿן געוואָרן צווישן דעם דרײַצעטן און דעם זיבעצעטן יאָרהונדערט איז געווען ענלעך צו עלטערע שטעט: זי האָט זיך אַנטוויקלט בײַ אַ טײַך צוליב דעם גרינגן טראַנספּאָרט און קוואַל פֿון וואַסער; אַרום אַ שלאָס וווּ ס׳האָבן געוווינט די שׂררים, וואָס פֿלעגן אָפֿט „באַשיצן“ די פֿאַרבעטענע און נײַ־צוגעקומענע ייִדן.

ס׳רובֿ שטעט זענען געווען אַרומגערינגלט מיט אַ מויער, געהאַט אַ מאַרקפּלאַץ, אַ קאַטעדראַל, קראָמען, הײַזער און קרומע ברוקירטע גאַסן. אויב די שטאָט איז געווען אַ קיניגלעכע האָט זי אויך געהאַט אַ שיינעם מאַגיסטראַט, וואָס דאָס האָט אונטערגעשטראָכן איר חשיבֿות.

אין פֿריִערדיקע תּקופֿות האָבן ייִדן געמוזט וווינען אין אַ ייִדישן קוואַרטאַל; אָפֿט האָבן זיי נישט געטאָרט וווינען אָדער אַרבעטן צווישן די שטאָטמויערן. האָבן ייִדן געדאַרפֿט אָנקומען צו דער לאַסקע פֿון פּראָווינציעלע פּריצים. יענע האָבן מיט גרויס חשק פֿאַרדינט פֿון ייִדישער אַרבעט, אַרענדעס און שטײַערן. שפּעטער איז דער קוואַרטאַל נאָך אַלץ געווען אָפּגעטיילט פֿון אַנדערע, אָבער זעלטענער דורך געזעצן ווי פֿון אַ נישט־געשריבענעם אָפּמאַך. ווילנדיק צי נישט ווילנדיק האָבן ייִדן געוווינט צוזאַמען. ווי נאָר ס׳האָבן זיך אין נײַנצעטן יאָרהונדערט באַוויזן די אײַזנבאַן מיט טראַמווײַען האָבן ייִדן, ווי אויך נישט־ייִדן, געקענט וווינען ווײַטער פֿון זייער אַרבעטפּלאַץ.

ייִדן האָבן אָנגעהויבן אַרבעטן בײַ פֿאַרשיידענע מלאָכות, ווײַל מע האָט צוגעלאָזט. נישט־ייִדישע צעכן האָבן זיך באַמיט זיי צו באַגרענעצן אויס מורא פֿאַר קאָנקורענץ. אין מערבֿ זענען ייִדן געווען כּמעט בלויז הענדלערס און מעקלערס; אין מיזרח זענען זיי קודם געוואָרן בוי־אַרבעטערס, שנײַדערס, שמידן, ברײַערס און בעקערס; שפּעטער זענען זיי אַרײַן אין די פֿרײַע פּראָפֿעסיעס (דאָקטוירים, אַדוואָקאַטן, אינזשעניערן) אד״גל.

אין יעדער שטאָט, ווי נאָר ייִדן האָבן זיך פֿאַרוואָרצלט און געהאַט אַ סטאַבילן עקאָנאָמישן מצבֿ, האָט מען גענומען שאַפֿן די טיפּישע ייִדישע אינסטיטוציעס: אַ קהילה אויף אָנצופֿירן מיטן קהלשן לעבן; אַ שול, אַ מיקווה, אַ בית־עולם, חדרים פֿאַר קינדער, ישיבֿות פֿאַר בחורים. שפּעטער, בפֿרט ווען ס׳האָט זיך אַנטוויקלט דער וועלטלעכער סעקטאָר, זענען צוגעקומען וועלטלעכע שולן און גימנאַזיעס. מיט אַ מנין ייִדן האָט מען שוין געקענט אָנהייבן שאַפֿן אָט די חבֿרות און זיי אויסהאַלטן דורך אַרויפֿלייגן שטײַערן אויף די פֿאַרמעגלעכע ייִדן. הייסט עס, ייִדן האָבן באַצאָלט טאָפּעלע שטײַערן (סײַ דער מלוכה, סײַ דער קהילה), אָבער אַנדערש וואָלט דער ייִדישער שטייגער ווײַט נישט אָנגעגאַנגען. יעדער קהלשער בנין האָט אַרויסגעוויזן דאָס אײַנגעפֿונדעוועט ווערן אינעם אָרט: פֿון הילצערנע שולן זענען געוואָרן שטיינערנע; פֿון חדרים און תּלמוד־תּורות אין ענגע דירות איז מען אַריבער אין מאָדערנע אייגענע בנינים. מיטן וואַקסן האָט דאָס ייִדישע לעבן אָנגעהויבן שפּרודלען דורך דער שטאָט.

פֿונדעסטוועגן האָט זיך אינעם נײַנצעטן יאָרהונדערט דער ייִדישער שטייגער אָנגעשטויסן אויף גרויסע שוועריקייטן. די אינדוסטריעלע רעוואָלוציע אין אייראָפּע איז געווען אַ קערפּונקט סײַ פֿאַר די שטעט, סײַ פֿאַר די שטעטלעך; דאָס האָט אין גאַנצן איבערגעאַנדערשט דעם אופֿן אַרבעטן, לעבן און אָרגאַניזירן זיך. דאגות פּרנסה, ענגשאַפֿט און בײַטונגען אין דער געזעלשאַפֿט האָבן אין די לעצטע צענדליקער יאָרן פֿונעם נײַנצעטן יאָרהונדערט דערפֿירט דערצו, אַז מיליאָנען ייִדן זאָלן אַוועק פֿון די שטעטלעך און זיך באַזעצן אין גרויסע שטעט, וווּ מע האָט געהאָפֿט אויף אַ בעסער לעבן. ווי אַ רעאַקציע אויפֿן עקאָנאָמישן מצבֿ זענען מיליאָנען ייִדן אין גאַנצן אַוועקגעפֿאָרן פֿון מיזרח־אייראָפּע, קיין מערבֿ־אייראָפּע און ווײַטער קיין צפֿון־אַמעריקע, דרום־אַמעריקע און ארץ־ישׂראל.

.avif)