The following stories are taken from a collection of autobiographies received during competitions held in 1932, 1934 and 1939 by the YIVO Institute in Vilna. The competition asked Jewish youth in Poland, between the ages of 16 and 22, to write short autobiographies detailing their day-to-day lives. These accounts are, therefore, first-person accounts written by interwar teens who were not professional writers. Their experiences and worldviews were generally limited by daily life, and it is precisely because of these limitations that their stories are profoundly interesting. Their memoirs are not objective documents; they are extremely personal and subjective interpretations of the events and forces which shaped the lives of their families: poverty and wealth, school, living in a shtetl, work, youth groups, and many other factors.

The lives that these young people describe are, on the one hand, quite unique and specific, documenting Jewish life on the brink of one of the darkest chapters of our history. At the same time their lives and stories also contain threads that may seem familiar to teenagers from other times and places. Like any teenagers, these amateur writers were full of confusion, joy, fear, curiosity, and idealism; they worried about friends, pleasing their parents, fitting in, getting an education, finding a job, rebelling, and surviving.

These personal accounts also reveal some of the diversity of Jewish experience, which occured even in small Polish towns. They remind us that "Jewish culture" is very hard to define and pin down. Most of these writers spoke Yiddish, but some spoke only Polish. Most were poor, but others came from wealthy families. Many were religious, and many others were more secular. It is also important to note that these few impressions do not comprise a comprehensive portrait of Polish Jewish life, or Polish Jewish youth, during that time. Yet, after all, these autobiographies are a unique and insightful resource, offering us an intimate glimpse into the lives of ordinary Jewish teenagers and young adults in the 1930s.

The Contest

The autobiographies in this section originally appeared as entries for an essay contest sponsored by YIVO, the Yiddish Scientific Institute, then located in Vilna, Poland. YIVO invited Polish Jews between the ages of 16 and 22 to send in their life stories in exchange for the opportunity to win cash prizes. YIVO mounted this effort to collect the stories in order to help researchers understand the lives of Jewish youth in Poland who were coming of age in the 1930s. They were especially interested in these experiences because the youth embodied the future of the Jewish people.

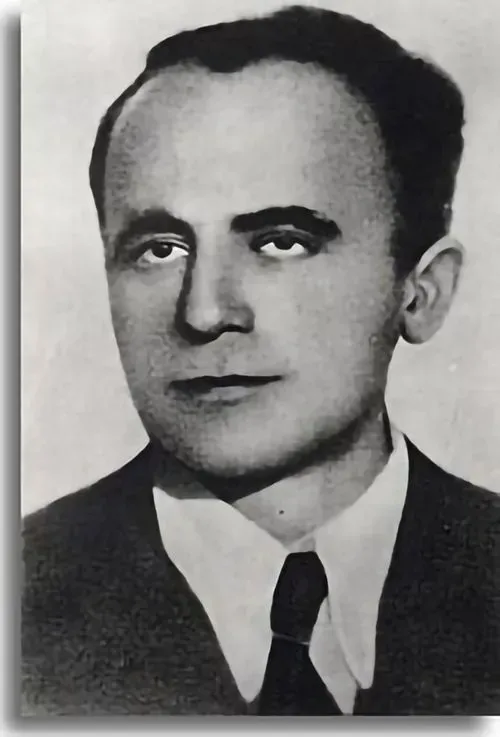

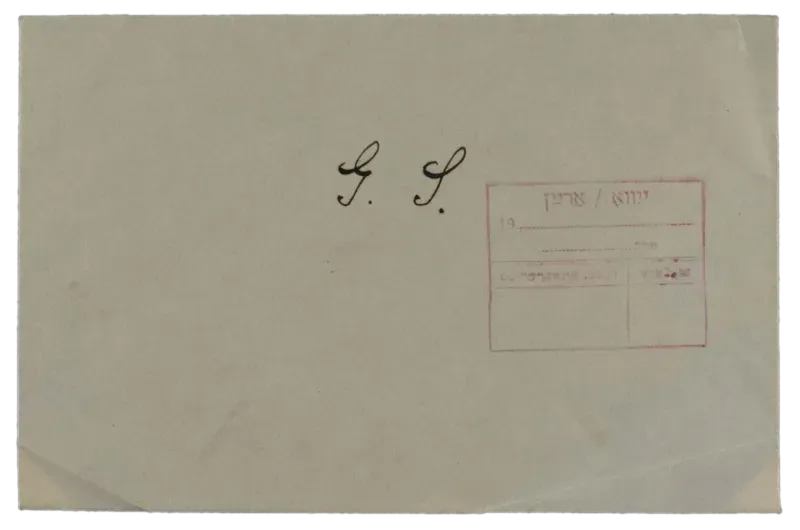

627 young people responded to the call. Many wrote in Yiddish; others wrote in Hebrew, Polish, and other languages. All wrote in the hope of winning a prize, but some writers also viewed the contest as an opportunity to pour out their hearts on paper. Contest entrants were guaranteed anonymity. Like many others who sent in material, the writer of this autobiography used a pseudonym.

Some 300 of the autobiographies survive and are stored in the YIVO Archives. The others were destroyed by the Nazis during World War II. The surviving documents were rescued, along with other looted YIVO property, after the war and brought to YIVO's new headquarters in New York.

קול פֿון יוגנט

די ווײַטערדיקע מעשׂיות נעמען זיך פֿון אַ זאַמלונג געשאַפֿן דורך אַ פֿאַרמעסט וואָס מע האָט אויסגעפֿירט אין די יאָרן 1934 און 1939 אינעם ייִדישן וויסנשאַפֿטלעכן אינסטיטוט (ייוואָ) אין ווילנע. פֿאַרן פֿאַרמעסט האָט מען געבעטן ייִדיש יונגוואַרג אין פּוילן אָנצושרײַבן קורצע אויטאָביאָגראַפֿיעס וועגן זייער טאָג־טעגלעכן לעבן. דעריבער זענען די מעשׂיות דירעקטע באַריכטן פֿון יונגוואַרג וואָס זענען בפֿירוש נישט געווען קיין פּראָפֿעסיאָנעלע שרײַבערס. זייערע איבערלעבונגען און וועלטבאַנעם זענען בדרך־כּלל געווען באַגרענעצטע, און דאָס איז דווקא אַ מעלה, וואָס ס׳מאַכט די מעשׂיות אינטערעסאַנט. קיין אָביעקטיווע באַשרײַבונגען זענען זיי נישט, נאָר עכט פּערזענלעכע, סוביעקטיווע אויסטײַטשן פֿון די געשעענישן און די כּוחות וואָס האָבן אויסגעפֿאָרעמט זייערע משפּחה־לעבנס: דלות און עשירות, שולן, דאָס שטעטלדיקע לעבן, אַרבעט אאַז״וו.

פֿון איין זײַט זענען די דאָ באַשריבענע לעבנס ספעציפֿיש און אויסנעמלעך אין דעם זינען וואָס זיי גיבן איבער ס׳ייִדישע לעבן פֿאַרן חורבן. פֿון דער צווייטער זײַט האָבן אין זיך די אויטאָביאָגראַפֿיעס אויך טעמעס וואָס קענען זײַן באַקאַנט צענערלינגען פֿון אַנדערע צײַטן און ערטער. אַזוי ווי אַלע אַנדערע, האָבן אויך די יונגע מחברים איבערגעלעבט פֿרייד, צעטומלטקייט, פּחד, נײַגער און אידעאַליזם; אויך זיי האָבן געהאַט דאגות וועגן פֿרײַנדשאַפֿט, וועגן צופֿרידנשטעלן טאַטע־מאמע צי זיי זאָלן זיך אַרײַנפּאַסן אין זייער סבֿיבֿה אָדער זיך בונטעווען; בקיצור, וועגן דעם ווי אַזוי מע לעבט איבער די יונגע יאָרן.

אָט די אויטאָביאָגראַפֿיעס אַנטפּלעקן אויך דאָס פֿאַרשיידנקייט פֿון דעם ייִדישן לעבן אַפֿילו אין קליינע שטעטלעך אין פּוילן; זיי דערמאָנען אונדז, אַז ס׳איז נישטאָ קיין איינהייטלעכע ייִדישע קולטור. ס׳רובֿ פֿון די דאָזיקע שרײַבערס האָבן גערעדט ייִדיש; טייל, אָבער, בלויז פּויליש. ס׳רובֿ זענען זיי געווען אָרעמע, אָבער טייל האָבן געשטאַמט פֿון פֿאַרמעגלעכע משפּחות. געווען צווישן זיי סײַ פֿרומע, סײַ וועלטלעכע. דאָ מוזן מיר אונטערשטרײַכן, אַז די רעלאַטיוו קליינע צאָל אויטאָביאָגראַפֿיעס שעפּן נישט אויס די גאַמע פֿון דעם ייִדישן לעבן אין צווישנמלחמהדיקן פּוילן. פֿונדעסטוועגן זענען זיי אַן אויסנעמלעך טײַפֿער קוואַל וואָס גיט אונדז אַ איבערבליק איבערן לעבן פֿון פּשוטע ייִדישע צענערלינגען אין די 1930ער יאָרן.