I. Eastern European Jewish Political Life Before and During World War I

Prior to World War I, the three largest empires in Eastern Europe were the Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian Empires. At that time, the majority of Eastern European Jews lived in the Russian and the Austro-Hungarian Empires.

.avif)

...in the Russian Empire

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was tremendous political unrest in the Russian Empire. While primarily this was directed against the regime, the Tsarist government did not hesitate to stir up anti-Jewish sentiment, and it allowed violent outbursts against the Jews as a means of distracting attention from larger systemic problems. Violent pogrom 's erupted against the Jews, which resulted in mass death and destruction. Emigration was encouraged as a partial solution; a large number of Russian Jews fled to Western Europe, other parts of Eastern Europe, and to North and South America. In addition to the pogroms, there were other anti-Jewish policies, such as restrictions on Jewish employment and quotas on the number of Jews allowed in schools, universities, and certain professions.

Russian Jews suffered greatly during the World War I. They were mistrusted, and Hebrew and Yiddish newspapers were banned because of the suspicion they were being used for espionage. Jewish communities also were expelled from areas near the frontlines based on the belief that the Jews would sabotage Russian defenses. When the Russian Tsar was overthrown in 1917, emancipation was granted to the Jews by the new provisional government. However, any positive effect of emancipation was muted because Civil War (1918-1921), with its darker side, raged in the areas most populated by Jews.

...in the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Officially emancipated in 1867, Jews in the Austro-Hungarian Empire enjoyed more freedoms than their brethren in the Russian Empire. They were not subject to restrictions on education, residency or occupation. Nor were Jews subjected to government sponsored pogroms. However, there still were severe economic differences between Jews and non-Jews in different sections of the Empire, and among the Jews themselves. Although at the beginning of the 20th century, the Jews of Vienna, for example, were highly assimilated into the Viennese economy and socially acculturated, yet the Jews of Galicia largely were impoverished and segregated from their neighbors. Similarly, Jews in Budapest were largely integrated into Magyar (Hungarian) culture and the larger economy, while the Jews of rural Hungary lived much like their Orthodox brethren in Galicia.

II. Political Changes after World War I

One of the first after effects of the First World War was the redrawing of the political map of Europe, something that was accomplished at the Peace Conference at Versailles, which opened on January 12, 1919. The large Central Power empires were broken up. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was completely dismantled and new countries, with substantial Jewish and other minorities, emerged in Eastern Europe. A part of this process was the framing of a Minorities Rights Treaty (1919). The newly formed Eastern European states of Poland (over 3 million Jews), Romania (850,000 Jews), Czechoslovakia (375,000 Jews), Lithuania (115,000 Jews), Yugoslavia (68,000 Jews) and Bulgaria (48,000 Jews) were each obliged to adopt this policy which was intended to ensure the rights of ethnic minorities, including Jews, within their borders. It also involved granting citizenship to minority groups and allowing them to organize and to maintain a cultural identity including establishing their own schools and speaking their own languages, while still remaining a part of the newly formed political state in which they lived. Thus, Jews in Eastern Europe found themselves officially emancipated and enfranchised as citizens of the new postwar republics instead of Empires.

However, many of the countries that signed the Minorities Rights Treaties, did so to gain the support of the United States, United Kingdom, and France. But soon these countries began ignoring parts of the treaty that were not to their liking. Economic discrimination against Jews was common. Quota systems limited Jewish entrance into higher education, and limits (or even barring of Jews) in certain professions became the norm in the new states. Part of the economic discrimination resulted from the fact that at the end of World War I, Eastern Europe, including most of the Jewish communities within that area, was in economic ruin. Many homes and means of livelihood had been completely destroyed during the war, and many people, as well as governments, believed that if they excluded Jews from the economy, there would be more opportunity for others.

.avif)

The Minorities Rights Treaties guaranteed cultural autonomy to the Jewish community, and that they would be able to maintain their own ethnic schools which taught their religion, culture and languages. But the new states did not want to support Jewish cultural autonomy at the expense of native nationalist movements. Funding was eventually cut for Jewish communal administration and educational programs resulting in communities having to institute their own system of taxes to support them, effectively creating a double tax on Jewish citizens. The Jews of Eastern Europe thus became heavily dependant on support from American Jewish relief organizations, such as the American Joint Distribution-AJD, which supported soup kitchens, job retraining and other programs.

III. Post-World War I: The End of the Russian Empire and the Beginning of the Soviet Union

![Jewish farmer, Brest area [Brest Litovsk, Brisk], Poland [now Belarus], 1920s-1930s. The World ORT Archive Ref. psa0135](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6891ffac7571e63c0e0f2860/6891ffac7571e63c0e0f2b2c_jewishfarmer.avif)

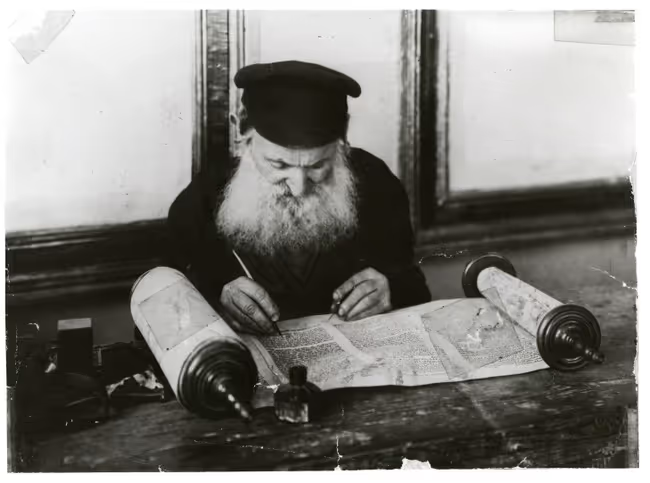

The Russian Empire which had been at war since August 1914, collapsed in 1917. The Bolsheviks came to power in November 1917 and the Tsarist family was later executed. In the newly formed Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), the Jews were finally offered political and economic emancipation, and anti-Semitism was officially banned. The 2.8 million Jews of the USSR were declared equal citizens, and freed of restrictions on education, occupations and residential opportunities. Jews were recognized as a national, culturally autonomous group. There even was a Jewish branch of the Communist party, called Yevsektsiia. Yet, there were some indications that the Jews were not truly autonomous. They were free to use Yiddish, but Hebrew was banned as a bourgeois language. Conversely, Jews were allowed to create their own schools including a Jewish University.

Although the new Soviet state initially was willing to support secular Jewish activities and use of the Yiddish language, it was opposed to all organized religions. The Soviet authorities suppressed all religions, closing houses of prayer including churches, synagogues and mosques. The government closed religious schools and banned the printing of religious books. All non-socialist Jewish organizations, including the Zionists, came under attack. Jewish communal organizations were forced to disband. Religious Jews were persecuted, and considered enemies of the State.

Members of the middle class, including middle class Jews, were also persecuted in the Soviet Union. A large number of Jews had been involved in commerce prior to the Revolution and, as such, found themselves generally outside the new Soviet economic system. Then the Soviet regime offered the Jews land in the Crimea, Belorussia, and Ukraine on which to build farming communities. With equipment provided by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, many Jews settled into these agricultural communities despite the hardships. In 1929, Jews were even offered Birobidzhan as their own autonomous region in Siberia. These settlements eventually failed.

After Joseph Stalin's rise to power, the cultural concessions granted the Jews by the central were withdrawn. The Yevsektsiia was abolished; Jewish cultural institutions were closed and the leadership killed or imprisoned; and Jews who had been Communists loyal to the government were systematically purged.

Jewish Political Parties

.avif)

Prior to the First World War, many Jews sought to address their lack of political power and equality. The pressing need to save Jews from the immediate dangers of bodily harm was the impetus for radical change. The rising nationalism in many Western countries also had led to anti-Semitism, and Jews found themselves less able to live in narrowly defined national societies. Jews, regardless of their citizenship, were not afforded full rights as members of society. Two main strategies were employed against anti-Semitism and civil inequality: one was a search to change the society as a whole to create a more equal society and, the second, came in the form of Jewish Nationalism, which promoted Jewish separation from these oppressive societies. As a large number of secular Jews became involved with various Socialist, Communist and Anarchist organizations in their search to create a more equal society, Jews also further developed Zionist nationalist politics.

Eastern European society in the interwar period was extremely multi-cultural. Peoples speaking different languages, practicing different religions and holding their own ethnic customs lived side by side in cities and villages. Although some Jews in Eastern Europe were highly assimilated and spoke the language of the majority population in addition to Yiddish, the vast majority of Jews spoke Yiddish, read Hebrew prayers, and lived by Jewish traditions.

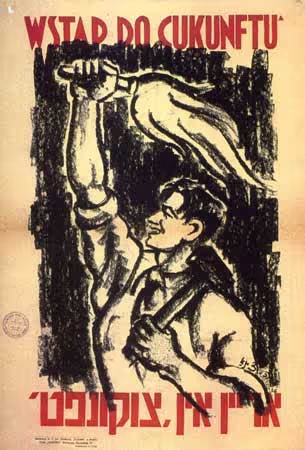

Many of the early Jewish Socialists, Communists and Anarchists spoke non-Jewish languages. However, in order to be better able to bring their ideas to the majority of the Jewish masses, they decided to express them in Yiddish, the language spoken by the majority of Jews. The most important Jewish Socialist organization, the Union of Jewish Workers in Lithuania, Poland and Russia also known as the Bund, was created as a response to the desire to introduce Marxist ideas to Jewish workers who largely spoke Yiddish. Jewish nationalism arose primarily in the form of the Zionist movement. Variations and combinations - Zionist and Socialist - also developed, including various forms of Socialist Zionism and religious Zionism. Most of these groups, both the Zionist and Socialist, originated before the First World War, when it was illegal to form such organizations. The early groups had to meet clandestinely. The need to create secret political organizations and the willingness of the early members of these political parties to risk arrest and in many cases exile to Siberia, indicate their high level of commitment to finding solutions for the problems plaguing the Jews of Eastern Europe. After World War I, when Jewish political organizations became legal in most of Eastern Europe (except the Soviet Union), these early clandestine organizations emerged from underground; other Jewish organizations representing more conservative elements seeking non-socialist integration into society and religious political groups also began to arise.

Most Jewish political parties sponsored youth movements, a great innovation in the Jewish world. In the early 20th century, youth movements became extremely important to Jewish political parties. Not only did they recruit and train future members - and especially future leaders of the organization - but many of the youth groups provided the "muscle" for the organization, be it in the form of a small military unit to protect Jews from violent attacks during pogroms or political rallies, or as agricultural workers training to start a new life in Palestine.

Many of the Jewish political parties also sponsored important communal activities, ranging from the building of schools, to cultural programs, which included lectures, theatrical performances, and the like. At the same time, the parties often competed for prominence and power within the Jewish world, especially within the Kehillah, which oversaw religious affairs such as public prayer, supervision of kashrus, religious education, and welfare activities. Before the World War I, in many communities the Kehillah members were chosen by a few prominent families or members of the community. After the World War I, democratic election of the leadership of the Kehillah became more widespread. Representatives of secular organizations such as the Bund or Zionists then were able to become Kehillah members as a result of this development.

A. Jewish Socialism

By far the largest organization of Jewish Socialists was the "Bund." Its platform called for a culturally autonomous Jewish people living in a socialist state. There were other smaller organizations such as the Jewish Social Democratic Party (ZPSD), which had similar goals and which eventually joined with the Bund. Another significant Jewish socialist organization, Poalei Zion, the Jewish Socialist Workers' Party combined the ideas of Socialism and Zionist. While there is an important nationalist component to Poalei Zion, the fact remains that the Bund and Poalei Zion often combined forces politically; whereas, Poalei Zion and other Zionist factions were not always easy political allies. The Jewish political scene in the region was full of nuance and complexity. No black and white distinctions described or predicted the variety or duration of alliances or separations.

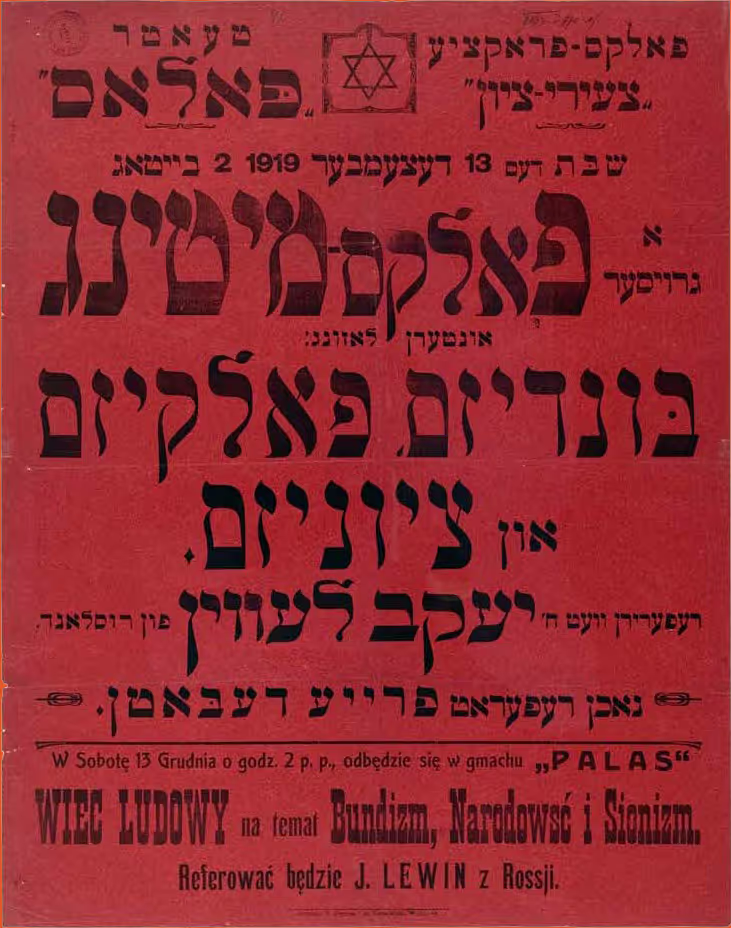

BUNDISM

In 1897, the Union of Jewish Workers in Lithuania, Poland and Russia, otherwise known as the "Bund" was founded in Vilna, Poland. The Bund sought to bring about cultural autonomy for Jews within a socialist state. It believed that Jews did not need to emigrate in order to solve their problems, but rather, they proposed that a more realistic goal was to transform the states and societies in which the Jews were living. The Bund sought to enlist the solidarity of Jewish workers to achieve this goal, as they rejected integration or assimilation into the main society. Their goals and perspective also separated them from other national socialist groups, since these were not interested in the sponsorship of Jewish cultural activities.

The Bund went through a number of transitions. Before the World War I, like many other Jewish and non-Jewish political groups, the Bund was illegal and members would have to meet in secret. At that time young people largely comprised the membership. In fact, in many villages, despite the youth of the local Bund membership, it could influence the affairs of a village, traditionally ruled by older members of the community. The Bund also overturned tradition by welcoming both male and female members.

To understand the significance of this innovation, one must recall that women did not have the right to vote in the United States or in many European countries at that time. The incorporation and validation of women members in a political organization was a very radical departure from the norm. Perhaps the most important association of the Bund and Jewish culture came with its support and insistent use of the Yiddish language as the only way to reach out to the masses, and as a way to legitimize the culture of the "man in the street". After the World War I, the organization was legalized in most parts of Eastern Europe. In the USSR, the Bund became part of the Communist Party. In Poland and Lithuania, the Bund highlighted its cultural mission and remained part of the democratic socialist movement: it focused its interest on Jewish cultural nationalism and the preservation of Jewish cultural identity.

The Bund also became more nationalist in its politics, embracing specifically Jewish causes. When injustices were perpetrated against Jews - pogroms or other government anti-Jewish actions, the Bund, after noting that their fellow (non-Jewish) socialists did not intervene, sought ways to specifically protect the Jewish people. They organized protests against government actions against Jews, sometimes in conjunction with non-socialist, Orthodox Jewish organizations such as Agudas Israel--Isroel-Yisroel. The Bund also created self-defense units to defend the local Jewish communities against pogrom's However, the main function of the Bund was always to support the worker; it successfully called strikes in a number of areas, which lead to vast improvements in working conditions. The Bund sponsored various programs that offered practical support to workers, including labor unions, strike funds, and other supportive assistance.

It also sponsored a wide range of cultural activities, from schools, to public lectures and entertainment events. It particularly supported activities, which used and promoted the Yiddish language, held to be the true language of the worker.

Although the Polish Bund was a Social Democratic organization, which officially opposed organized religion, Bund members (though not the leadership) on the local level still were often religious Jews. They attended synagogue, celebrated Jewish traditions, and led Jewishly centered lives. In the town of Swislocz, for a good example of this seeming contradiction, factory workers preparing to strike swore on Jewish ritual objects (in this case on tefilin) not to return to work until all of the strike demands were met.

B. Jewish Nationalism

A number of Jewish political organizations had Jewish nationalist agendas. Many also had cultural nationalist interests that simply strove for Jewish cultural autonomy. Others, however, were specifically interested in political autonomy. The largest and most important Jewish nationalist organization, the Zionist movement, sought Jewish political and cultural autonomy in their own nation-state. The majority of Zionists envisioned establishing this independent nation in the historical land of Israel, which at that time was Palestine. The Zionist mainstream organization had several off shoots including the religious branch of the party, Mizrachi, and the Revisionist branches which included the right wing youth movement Betar.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)