Yiddish, A Fusion Language

The famous linguistic scholar Max Weinreich called Yiddish a "fusion language". What should we take this to mean? Indeed, it might surprise you to learn that most modern languages derive from other languages, what linguists call "stock languages." English, for instance, derives from the "stock languages" Danish, French, and Latin (and has a sprinkling of "loan words" from yet other languages, even Yiddish and Hebrew). English only appears to be one pure system to English speakers who are neither connoisseurs (French-derived) nor mavens (Yiddish-derived)-or who are simply not concerned with the derivations of their words on a day-to-day basis.

Yiddish is similar to English in just this way. The main components of Yiddish derive from German, Hebrew, and several Slavic languages (especially Polish and Ukranian). Moreover, we can generally recognize which words derive from which stock language. Now we begin to understand how Yiddish is different from English. Yiddish was almost always spoken by bilingual or multilingual speakers; not all Yiddish speakers spoke Polish, for instance, but they often realized when they were speaking with Polish-derived words, or, for that matter, German- or Hebrew-derived words. The reason for this is simple: unlike English speakers who mostly lived among other English speakers, the Jews lived among speakers of other languages. At times they lived among Germans, at other times among Poles or Ukrainians. Moreover, depending on the linguistic or cultural context they were in, Jews would emphasize the Slavic words in their vocabulary or the Hebrew ones.

Internal Bilingualism: Yiddish and Hebrew

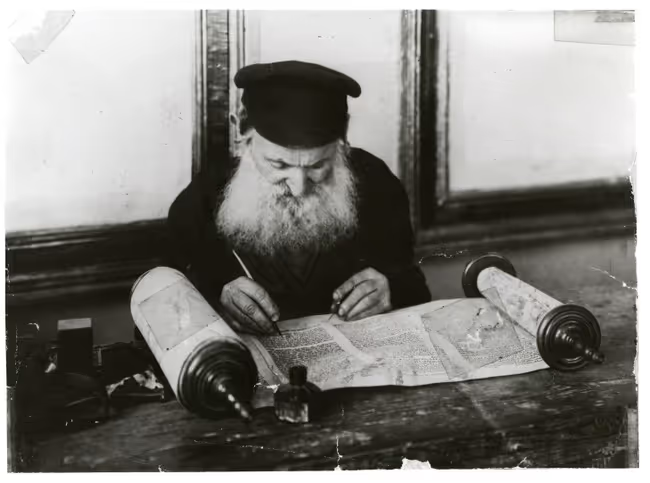

Internal bilingualism in the context of Jewish Eastern Europe refers to the two Jewish languages that took on complementary functions within the Jewish sphere. On a basic level, Hebrew was the holy language as compared to the Yiddish vernacular, which was the language of daily speech. Hebrew was bound more closely to written text so it follows that Hebrew became associated with men in the community-who received and benefited from formal training that was not commonly available to women. But these dichotomies simplify the reality. Hebrew was the language of Jewish prayer, of the Bible and the Mishnah (the collection of post-biblical laws and rabbinical discussions of the 2nd century CE, forming part of the Talmud), and therefore was the language used for scholarship and education. However, Yiddish also had an important role in the sphere of the learned. For example, the same letter or responsum a rabbi wrote in Hebrew he then relayed orally in Yiddish. Yiddish also was the language in which Talmudic debate played out. Also, the tales and teachings of the Hasidic rebbes were told and written in Yiddish. Although it is true that few women learned Hebrew, many men knew only enough Hebrew to read their Siddur (prayer book). Ostensibly written for female readers alone, Yiddish prayer books (tkhines in Yiddish) and popular translations of the Bible (tsenerene) were in reality read by men and women alike. Yiddish played a role on certain religious occasions as well. Yiddish song was customary at any Jewish wedding and Yiddish songs and plays were central to the celebration of Purim. Although Hebrew was the language of the synagogue, its words, idioms, and structure permeated Yiddish. But without a clear divide between the religious and secular, yidishkayt infused all areas of Jewish life.

External Multilingualism.

We mentioned earlier that most Yiddish speakers were cognizant of the compound nature of the language because of their constant exposure to other languages in daily life. For most Jews, knowledge of other languages was oral in nature and varied widely in scope. A Yiddish speaker living in 19th-century Warsaw might have known enough Polish to conduct business with his neighbors, a little German to communicate at the Leipzig Fair, and some Russian, the language of the state, to communicate with officials. For the most part, Jews functioned in the external world as an economic bridge among different peoples.Thus their knowledge of languages other than their own native Yiddish was necessary to make this possible. Educated Yiddish speakers often were multilingual to a far greater extent- they could read difficult texts in other languages. Elye Bokher (1469-1549), known to his Christian contemporaries as Elia Levita, was born in Germany and active in Italy. As a scholar and teacher he taught Hebrew to a Catholic Cardinal in Rome. Consider his language expertise: he wrote a Hebrew grammar book, composed a Latin-German-Hebrew-Yiddish dictionary, and wrote poetry in Yiddish, most famously an epic poem entitled Bove-bukh, modeled after Italian sources!

True, Yiddish, like any language, also acted as a kind of social barrier shutting out the cultural assimilation that often occurs in the wake of linguistic assimilation. In place of a cultural life grounded in these external languages, Jews created a rich and variegated Yiddish culture all of their own. At the same time, Jews' continuing openness to languages other than their own allowed Yiddish language and culture to flourish. In Eastern Europe perhaps the possession of a Jewish language in which they lived and in which their culture grew, gave Jews the confidence to be resilient in the face of other cultures, as well as receptive to some aspects of those other cultures.

Yiddish, a Jewish language.

The awareness of the "hodge podge" composite nature of language attended the Jews when speaking any of the many Jewish languages, of which Yiddish was only one. Ladino, another popular Jewish language-with component parts mostly from Spanish and Hebrew-is written in Hebrew letters, as are all Jewish languages. Hebrew acted as a kind of cultural cement for the Jews and safeguarded their common history, religion, and religious practice. Throughout the many Jewish migrations and settlements during the Diaspora, the Jews put Hebrew (the language of Jewish prayer and study) in their "linguistic suitcase." leaving behind the vernacular language they spoke in a given place, only to replace it with another Jewish language once they were resettled in a different linguistic context. Some of the Jewish languages were only temporary necessities and not intended to generate a long-lasting culture. Ladino was different, and Yiddish was unique.

The History of Yiddish: Its Uniqueness as a Jewish Language

We can say that Yiddish was unique among Jewish languages in that it somehow jumped into the linguistic suitcase. According to Max Weinreich, founder of YIVO, Yiddish, like a number of European languages, emerged in cities on the banks of the Rhine in Germany around the year 1000 C. E. Jews from other parts of Europe settled there and slowly absorbed the vocabulary (words) and syntax (sentence structure) of their German-speaking neighbors. With time, the mixture of the language they spoke and the Germanic-language elements they had adopted, fused to create a new indigenous language, which was the basis of Yiddish. But Yiddish gained independence as a language when Yiddish speakers moved outside the German domain and continued to speak Yiddish. "Ashkenazi" Jews (Ashkenazi is the old Hebrew word for German), named for the place from which they originated, settled in Poland beginning in the 14th century and kept on adopting new linguistic elements without having shed the language they created in Germany.

The meeting of Yiddish with the Slavic linguistic world generated profound changes. These resulted in what one scholar described as a "Slavic culture with a German-based language living in a Hebrew library." So, although Yiddish vocabulary derives overwhelmingly from German, it adapted to its Slavic surroundings. How can we measure the changes that Yiddish underwent in the Jews' shift eastward to Poland? The Yiddish spoken by Polish Jews is markedly different from the Yiddish spoken by the Ashkenazi Jews who stayed in Germany and whose Yiddish is almost devoid of any Slavic element. In the Slavic context, Yiddish could not be perceived as simply another German dialect since it bore little resemblance to its neighboring languages. Why is it that Ashkenazi Jews always put Yiddish in their linguistic suitcase? The critical mass of their numbers and the autonomous nature of their social and cultural institutions guaranteed the independent life of Yiddish because it was firmly enmeshed in every aspect of Jewish life and culture.

What are the exact proportions of the component parts of the Yiddish language? A frequent estimate is that Yiddish is around 70% German, 20% Hebrew, and 10% Slavic. The large German component may be surprising even to Yiddish speakers. But what makes that language really Yiddish is the crucial role non-German components play in coloring its style and texture.

Throughout its existence, many have dismissed Yiddish as just another dialect of German, and an ugly one at that. This criticism raises the question, "What is a language?" To that, Max Weinreich famously answered, "...A language is a dialect with an army and a navy." History has shown that the endurance of a language, its continual growth, depends largely on whether it enjoys the status as an official language of a country and thus functions as the protected repository of its culture. With this in mind we may better appreciate the achievements of Yiddish language and culture. These emerged into the modern era in the mouths of a dispersed population forced to learn other languages in order to belong and survive. With neither a country nor a government to safeguard Yiddish-and lacking both "an army and a navy"-in the modern period alone, the Yiddish language nourished a world-class literature, spawned countless newspapers and journals, fed a flourishing theatre, and inspired the founding of ongoing institutions and political movements. From the early 19th century until the latter half of the 20th century, Yiddish secular culture competed in ambition and accomplishment with other European cultures. Let us now turn to some of these achievements.

Modern Yiddish Literature.

Modern Yiddish literature developed at a fast clip, a characteristic common to many "minor literatures." An example of a major literature is French or English; each developed over hundreds of years, with a critical mass of readers and writers that was one of the largest in Europe. In contrast, Rumania or the Czech Republic possess "minor literatures" that began relatively later once writers of these nationalities began appreciating the distinctiveness of their cultures and languages and began writing in this spirit by emulating the products of major literatures. Likewise, modern Yiddish literature got its start at the beginning of the 19th century and spawned myriad literary styles and genres in a matter of just a few decades

Modern Yiddish literature was conceived under the influence of the Jewish Enlightenment movement in Eastern Europe that first began at the end of the 18th century. The Enlightenment Movement (Haskalah in Hebrew, in Yiddish Haskole) was an effort on the part of a group of enlightened Jews, called maskilim, to "reform" their Jewish brothers and sisters on a variety of levels with the intent to improve their lives and how they were perceived in the eyes of the world. They believed that Jews should dress more like their neighbors and shed their "Jewish clothing" (such as the caftan); they should learn more than just the rudiments of the surrounding language, should stop avoiding the country's school system in favor of a strictly Jewish education, and should choose more productive vocations. These issues and arguments animated the plots of the first examples of modern literature penned by maskilim. Too often the heavy-handed didacticism of these works eclipsed their literary aspirations.

Initially, the Haskalah had a very precise language program: its adherents believed that the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews should speak Russian, the language of their country, learn Hebrew as the national language of culture, and to shed or forget Yiddish-since they saw it as superfluous and a language with "little cultural value". What was the literary implication of this? Jewish writers should contribute to the growth of a Hebrew literature. And most maskilic writers began their careers writing in Hebrew. One of the greatest writers of the early maskilim was a schoolteacher named Sholem Abramovitsh.

My embarrassment was great indeed when I realized that associations with the lowly maid Yiddish world cover me with shame. I listened to the admonitions of my admirers, the lovers of Hebrew, not to drag my name in the gutter and not to squander my talent on the unworthy hussy. But my desire to me useful to my people was stronger than my vanity and I decided: come what may, I shall have pity on Yiddish, the outcast daughter of my people.

Abramovitsh's identification of the Yiddish language as a female, a "lowly maid" and "outcast daughter" was widespread among the maskilim who considered Yiddish inferior to Hebrew. At the same time, a group of them believed it was necessary to write Yiddish in order to teach the masses the lessons of the Enlightenment.

It might be due to this shame over writing in Yiddish that Abramovitsh wrote under the pseudonym Mendele-the-Book-Peddler. Throughout much of the 19th century, Jews living in the shtetlakh relied on traveling merchants to buy household items, ritual objects, and books. Capitalizing on the familiarity of a traditional peddler, Abramovitsh had Mendele introduce his stories of Enlightenment-stories that might otherwise have been spurned by most Ashkenazi Jews suspicious of Haskalah.

…I am called Mendele the Book-peddler. I am on the move most of the year; at one time I am here, at another there. I am known everywhere. I make my rounds throughout Poland and carry all sorts of books from the Zhitomir printing press. Aside from books, I carry prayer shawls, shofars, mezuzas. Sometimes you can also buy from me brass and copper wares… But this is beside the point. What I want to tell you has nothing to do with this. This year 5624 [1863-1864]-and it happened on Hanukkah-I drove to Glupsk where I counted on making a little sum by selling wax candles. Never mind, this too is beside the point. Arriving in town-it was Thursday, after the morning prayer-I drove, as I am used to, straight to the synagogue…

Modern Yiddish Literature.

Readers habituated to Yiddish translations of the Bible might not have understood the modern concept of an author, but they certainly related well to an itinerant salesman barely able to tell his story because he is too busy advertising his wares.

Although there were Yiddish writers who preceded Abramovitsh, he was the foremost Yiddish innovator. In artistic masterpieces, he reproduced Eastern European Jewish life of the 19th century in all its shadow and light, from undernourished children and heartless officials, to luftmentshn-Jewish men with their heads in the clouds and without visible sources of income-and saintly Jewish mothers. Although he was satiric and criticized the behavior of his fellow Jews, his stories raised the bar for Yiddish writers and injected pride into writing Yiddish.

An author named Sholem Rabinovitsh entered theYiddish literary scene in the early 1880s and became the heir to Abramovitsh under the pen name "Sholem Aleichem," meaning Hello, how do you do?, the conventional greeting in Yiddish. And, as opposed to the critical edge of Abramovitsh's work, his pseudonym implies just how warm and hospitable his literature was to his readers. Most people today know him because of Fiddler on the Roof, a musical play that was based on a novel originally entitled Tevye the Dairyman, which he began writing in the 1890s. In general, Sholem Aleichem's works blend humor with moments of poignancy that appealed to masses of readers. But the first measure of formal acclaim came in 1888 when he published Di yidishe folksbibliotek, the first anthology of modern Yiddish literature. With it, he attracted prestige to the burgeoning literary movement and the attention of more writers. Although he eventually moved to New York, Sholem Aleichem was an important Zionist and wrote many stories that promoted Zionist ideas to his readers.

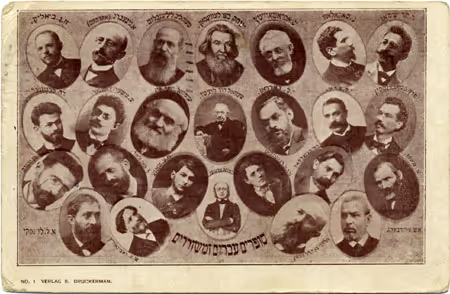

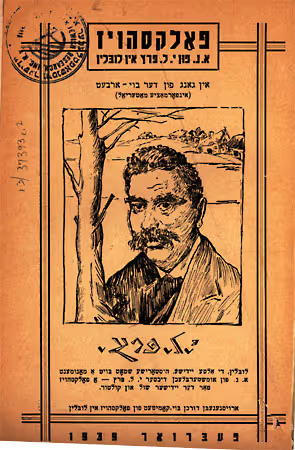

The names of Mendele Mokher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem are often uttered together with that of a third writer, Yitskhok Leybush Peretz (1852-1915). Together they are recognized as the "classics" (di klasikers) of modern Yiddish literature. Peretz grew up in a cultural context that was more Polish than Russian and lived much of his life in Warsaw. He wrote essays, poetry, and drama, but his short stories were his greatest achievements. In them he combined sketches of real life people with flights into the romantic. The many poor and humble characters he drew, like Bontshe the Silent (Bontshe shvayg), were not crushed by the difficulties of their lives because they had faith in a heavenly world to come.

In Peretz's story If Not Higher, a disciple of a Hasidic rebbe boasts to a Lithuanian Jew that his rebbe goes to Heaven everyday instead of attending morning prayers. Skeptical of such a fantastical story, the Lithuanian hides beneath the rebbe's bed one night determined to find out the truth about his mysterious morning activity. He watches from this hiding place as the rebbe, instead of putting on his caftan, puts on peasant clothes and then follows the rebbe as he makes his way to the forest. He watches him cut wood and deliver it to an old and sick woman. When he returns to the rebbe's disciple who again boasts that his rebbe ascends to heaven, the Lithuanian responds, "If not higher."

As opposed to Abramovitsh who sought to teach his fellow Jews through his literature, Peretz envisioned the creation of a secular Jewish culture sustained in part by its literature. This is why it was so important to him to encourage others to write Yiddish. His home in Warsaw became a shrine to which budding Yiddish writers made pilgrimage. The short-story writers Avrom Reisin (1876-1953), I.M. Weissenberg (1881-1938), Der Nister, Rokhl Fraydenberg and Rokhl Korn, playwrights Dovid Pinski (1875-1959), Peretz Hirshbein (1880-1948), Yehoash (who translated the Bible into a modern literary Yiddish) and the best-selling novelist Sholem Asch (1880-1957) are only some of the most famous Yiddish writers who visited Peretz in the early days of their careers. Each with his unique voice, they contributed to Peretz's ideal of Jewish literature as one grounded in Jewish traditions and Jewish history, one encompassing the totality of Jewish life.

Learn More About Yiddish Literature

Isaac Bashevis Singer was one of four children born to Rabbi Pinkhes Menakhem and Basheva Zinger. Israel Joshua, his older brother, was the family rebel. He was a painter, fiction writer, and draft dodger. Hinde Esther, his older sister, was married off to a diamond cutter in Brussels, a man she had never set eyes on, because who else would want to marry an epileptic? She later got back at her parents by describing her sad life in works of fiction. Moyshe, I. B. Singer's younger brother, remained Orthodox and perished, along with his mother, in the Warsaw ghetto. And Itshele-Isaac? He, too, became a professional writer in Warsaw, joined up with his brother, I. J. Singer, who had emigrated to the United States, and ended up winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978.

For three out of four children in a single family to become successful writers is a bit unusual. But the mix of tradition and rebellion is not a bit unusual -not in the history of modern Yiddish literature. The first modern Yiddish storyteller was Reb Nahman ben Simcha of Bratslav (1772-1810), the great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov (1698-1760). Reb Nahman was a rebel within the world of tradition. How else to explain his fantastically elaborated stories about abducted princesses, desert islands, enchanted forests, and crippled beggars? Sholem-Yankev Abramovitsh (1836-1917) on the other hand, started off as your typical Maskil, or reformer. After leaving home with a band of beggars and learning German from a private tutor, Abramovitsh turned against the leaders of the traditional Jewish community and the educators of their young. Then he hit upon a brilliant way of reaching the masses of Yiddish-speaking Jews, not by writing in his own angry, modern voice, but by inventing the character of Mendele the book peddler, who would do the talking for him. Yet alongside the many novels that Abramovitsh-Mendele produced in Yiddish and later in Hebrew, he also labored over rhymed Yiddish translations of the Jewish liturgy, for of what use were the prayers to God if the person praying didn't understand a word of them?

Another approach to combining tradition and rebellion was that of Yitskhok Leybush Peretz (1852-1915). Law rather than literature was his first choice of profession. After being disbarred, however, for reasons that remain hidden to this very day, Peretz began writing satiric poems and stories about the shtetl, like the famous "Bontshe the Silent," first published in a socialist newspaper in New York City. But when Peretz saw how quickly Jews were abandoning their traditions in the name of socialism, he launched a rescue operation, by turning back to hasidic teachings and medieval folktales.

Isaac Bashevis Singer combined all three models of revolutionary traditionalism. He began his career in the spirit of Abramovitsh-Mendele, producing harsh exposes of Jewish life in Poland. Then, in 1933, he wrote Satan in Goray, one of the first historical novels in Yiddish. Set in the 1660s in Poland, Singer brought Satan back, first in the guise of the false messiah, Shabbetai Zvi, then, at story's end, through a dybbuk (a wandering evil spirit). After immigrating to America, Singer was shocked to discover what had happened to his beloved Yiddish language in the streets of New York City and Miami Beach. And so, in 1943, he turned to the writing of monologues in the voice of the Devil, directly inspired by the stories of Nahman of Bratslav. If the Yiddish-speaking Devil couldn't talk some sense into modern wayward Jews-

Prominent Yiddish Authors

Prominent Yiddish Writers, Their Lifespans and Significant Works

Dr. Mordechai Yushkowitz

Two Yiddish Poets: Moshe Leyb Halpern and Avrohom Sutzkever

Moyshe Leyb Halpern (1886-1932), one of a group of gifted American-Yiddish writers who called themselves di yunge (the Young), lived during one of Yiddish poetry's most robust eras. An immigrant to America, Halpern worked at whatever job he could pick up during the day, and then would later meet his friends in cafés to discuss literary matters and share his literary work. With little money and less time, the young writers pulled together anthologies of their work and brought new life and energy to Yiddish literature.

Halpern was born in the city of Zlochev, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.He left for New York at the age of twenty-two. He began his career writing German verse but eventually was swept up in the high tide of Yiddish creativity that peaked around the early 1900s. Halpern was not a poet who contemplated the refined and the beautiful. "Much as I struggle only to see what is beautiful, I see only what is repulsive, a piece of rotten carcass." In some of his best poems, Halpern depicted the moral and psychic impoverishment of the immigrant masses. This theme is explored in realistic terms in "Around a Wagon":

There are people who maybe go on bragging

That it's not nice to crowd around a wagon

With onions, cucumbers, and plums.

But if it's nice to shlep in streets after a death wagon,

Clad in black, and lament with eyes sagging,

It is a sin to go on bragging

That it's not nice to crowd around a wagon

With onions, cucumbers and plums.

Perhaps one should not be so pushy, so attacking.

One can, perhaps, crowd quietly around a wagon

With onions, cucumbers, and plums.

But if you cannot chase them even whip wagging,

Because earth's tyrant, our belly, nagging,

Wishes so-you must be evil to go on bragging

That it's not nice to crowd around a wagon

With onions, cucumbers, and plums.

The writer seems to be suggesting that poetry, in particular, and refinement, in general, are inimical to the staccato rhythm of an immigrant population: their day-to-day behavior is propelled by nothing more than survival, by filling one's "nagging belly." But the poet suggests this with irony; his verse proves just the opposite. His poetry effectively gives expression to images of the common street, and does so in thickly colloquial speech. The street's chaos is punctuated by the recurring line a hawker shouts in the marketplace: "onions, cucumbers, and plums". The common and chaotic of the street yield to rhyme, rhythm and thrilling poetry. Moreover, the narrator warns the reader playfully not to pass judgment on the hungry crowds.

Avrom Sutzkever (b. 1913), is one of the most celebrated figures of the literary movement Young Vilna formed between World War I and World War II. While imprisoned in the Vilna ghetto after the Nazis occupied the city in 1941, Sutzkever and his colleagues risked their lives to smuggle hundreds of rare books and manuscripts away from Nazi destruction. Sutzkever wrote the following poem during the war, one that became a rallying cry among his fighting colleagues and friends:

The Lead Plates of the Rom Printers

Like fingers stretched out through the bars in the night

To catch the free light of the air that is shed-

We sneak in the dark to grab up, as in spite,

The Rom printing plates, with old wisdom inbred.

We dreamers now have to be soldiers and fight

And melt into bullets the soul of the lead.

The Rom printing press, most famous for publishing the classic edition of the Babylonian Talmud, as well as many Hebrew and Yiddish books, was an institution of Jewish intellectual life and civilization to which Sutzkever, as a poet, was devoted. The Nazis thrust upon the Jews a nightmarish reality that called for him and his friends to transform the power of the word into armed resistance. Sutzkever's continued poetic output during the war demonstrates that his resistance to Nazi barbarity took many forms. He taught poetry in the ghetto and joined a partisan fighting unit. Eventually he made his way to the safety of Moscow. After the war, he settled in Israel where he lives today.

Sutzkever's career since the end of the war has been marked by both mournful remembrance and renewal. In 1948 he founded the leading Yiddish journal, "Di goldene keyt " (The Golden Chain), which reestablished a literary Yiddish presence in Israel after so many of its writers were killed and literary centers destroyed. His powerful and exquisite poetry has led specialists to nominate him as a deserving candidate for the Nobel Prize.

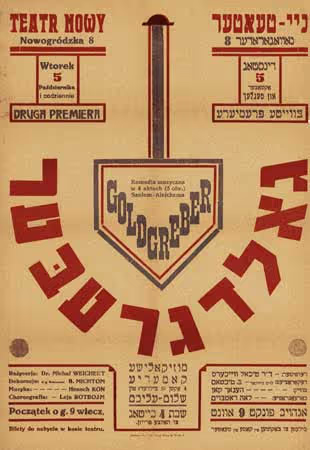

The Yiddish Theatre

The Yiddish theatre has always been a thriving aspect of Yiddish culture. Founded by Avrom Goldfaden in 1876, the Yiddish theatre evolved from the performances of a small number of scrappy tavern singers into theatre troupes lead by serious thespians of great celebrity. Although it boasted examples of very sophisticated drama, Yiddish theatre abounded and abounds with musically driven plots, incorporating dance and physical humor, and inclining towards the melodramatic. Sometimes Yiddish playwrights looked outward and sought to replicate content that was popular on European and American stages-many of William Shakespeare's plays, for example, were translated into Yiddish and produced. At other times, serious playwrights sought to capture the drama of Jewish life, depicting the tensions between modernization and tradition, and between the generations, or were historical dramas that portrayed a chapter of Jewish History.

The most memorable plays generated for the Yiddish stage are ones that engaged Jewish life and the Jewish past, while forging a distinctly Jewish brand of creativity. The most beloved Yiddish opera among Yiddish-speakers is Goldfaden's Shulamis, a love story set against the backdrop of ancient Israel. The Yiddish drama best known to international audiences is S. Ansky's The Dybbuk. The Golem is yet another Yiddish drama embraced by the Yiddish community and beyond for its originally Jewish artistic themes. All three of these plays drew on Yiddish folklore: Shulamis incorporates folksongs, and its plot is based on a Talmudic legend; The Dybbuk is laced with beautiful Hasidic legends; and the legend of the Golem of Prague animates H. Leivick's modern drama.

Although it got its start in Rumania and Russia in the late 1870s, the Yiddish theatre found its most welcoming home in New York City as early as the 1880s. At its height of popularity, ten Yiddish theatrical shows were playing in different venues simultaneously in the New York area alone. In the 1920s and 1930s you also could have attended Yiddish theatre in Chicago, Philadelphia, Montreal, or Buenos Aires among many other cities in the New World. By the 1950s, as the flow of Yiddish-speaking immigrants to the United States slowed, and as linguistic assimilation quickened, a dwindling Yiddish community could only support a fraction of such Yiddish theatrical life. If you look closely you may still see evidence of this era's theatrical creativity on the streets of Second Avenue, a place that will forever be synonymous with Yiddish theatre.

Yiddish Press

"Everyone read a Yiddish paper, even those who knew little more than the alef-bet. There were seldom many books in the average immigrant's home, but the Yiddish paper came in every day. After dinner, our family would leaf through it page by page, and sometimes my father would read some interesting items aloud. Not to take a paper was to confess you were a barbarian."

Anonymous quote from Irving Howe's World of Our Fathers

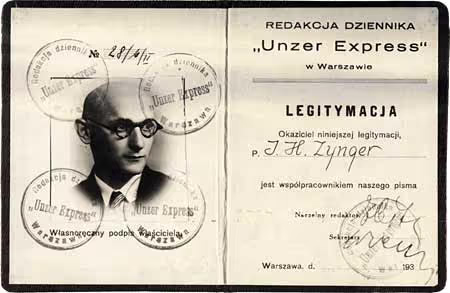

The first sustained Yiddish newspaper was founded in Odessa in 1862 under the Hebrew title Kol mevaser (A Heralding Voice). Since that time over a thousand Yiddish periodicals were established throughout the world-some lasting only months, others for decades. They ranged in scope and size from the dailies that serviced large populations in major cities throughout Poland and Russia, to the more modest ones dedicated to narrow interests, like the Byalistoker shtime, produced by and for the small pool of immigrants from the city of Bialystok scattered throughout the United States who hoped to maintain a connection to their birthplace. Of course competing Yiddish newspapers often represented a gamut of political voices. Although the Yiddish newspaper took on many forms, and matured a great deal, there were and are enduring traits that many Yiddish newspapers shard with their early progenitor, Kol mevaser. The most important of these traits is the privileged place literature enjoyed in so many of the major Yiddish newspapers. No matter how pedestrian a newspaper was, or how much it was concerned with reporting on daily news, it often featured a serialized novel by a well-known Yiddish writer or perhaps a poem. Readers of many a Yiddish literary masterpiece first read it on the pages of a newspaper before it was issued as a regular book. Sholem Aleichem published his stories in the popular newspapers of his day, as did Nobel Laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer.

The Yiddish newspaper that made the most profound impression on Jewish life was the New York-based Jewish Daily Forward (Forverts). It was founded in 1897 by Abraham Cahan, an immigrant writer and journalist. Cahan wanted to help his immigrant readers adapt to life in America as quickly as possible, and, accordingly, his paper familiarized them with many aspects of American life as they related to current events. In this regard, he also took a personal hand in a very popular section of the newspaper, Bintel Brief (A Bundle of Letters), in which readers sent in questions, often about their new lives in America, and Cahan responded, providing practical advice. In one letter a girl in a factory, who was supporting her family of eight, asked how to cope with a foreman who made "vulgar advances." In another, a worker confessed that he scabbed during a recent strike because he needed money to buy medicine for his sick wife. The Forward also took on issues of social justice, defended the rights of the poor and working class and in general became the voice of the Jewish immigrant. By the 1930s, the Forward had become one of America's most important metropolitan dailies with a nationwide circulation topping 275,000. It is still in circulation today, published weekly in Yiddish, English, and Russian editions (Russian being the language of the latest Jewish immigrant population).

Yiddish Folklore

Both native speakers and those who are only vaguely acquainted with the existence of Yiddish believe that it is a language with a life of its own, a language with its own mentality, and one with a particular set of attitudes. To the extent that this is true, it is attributable in part to the folklore embedded within it. Folklore, a nation's body of customs, legends, beliefs, and superstitions passed on by oral tradition, imbues a language with its distinctive character. The Yiddish language has a rich folkloric tradition that reveals a great deal about the culture of Eastern European Jewry. Yiddish cultural values, for example, can be felt in the most popular lullabies. An ideal shared by rich and poor Jews alike was that of the importance of learning, a value woven into the famous lullaby "Afn pripetshik" (On the hearth):

On the hearth the fire blazes merrily

And the heat is great

And the rebbe teaches little ones

To learn Aleph Beth

Children, study hard and remember well

Learning is the law

Another popular Yiddish lullaby is animated by the centrality of the merchant and trade to Eastern European Jewish life:

Under Yankele's cradle

Stands a pure white kid

Papa went traveling, Papa went trading

He will bring for Yankele

Raisins and almonds.

Yiddish proverbs attest to a hard-nosed ironic sensibility that accompanied the Ashkenazi Jew's abiding trust in God and confidence in his religious values. If praying did any good they'd hire you to pray, says one proverb. The proverb might sound like heresy. But the Jews who trotted out such a statement prayed, as required of a Jew, three times a day with devotion and fastidiousness. Irony was a way for the Jew to cope with the paradox of having to endure the continuous trials and tribulations experienced by the Jewish People as it, apparently, enjoyed the special status of being God's "Chosen People". Spare us what we can learn to endure, another proverb goes, referring to the Jews' ability to withstand great suffering. Suffering is something one has to learn to live with because it is forced upon you, but it is not something to be elevated or glorified.

One cannot leave the topic of Yiddish folklore without saying a word about "The Wise Men of Chelm", a body of stories about the fictionalized foolish men and women who live in a Polish town called Chelm. Although each story is witness to yet another extravagantly naïve and foolish thing the town elders have concocted, the stories contain an underlying wisdom and touch on deeply philosophical ideas.

Ten sayings from our "mame-loshn", our "Mother Tongue"

ייִדיש, אַ שמעלצשפּראַך

מאַקס ווַײנרַײך (1894־1969), ייִדישער לינגוויסט, היסטאָריקער און דערציִער. אין 1925 האָט ער מיטגעאַרבעט בַײם שאַפֿן דעם ייִדישן וויסנשאַפֿטלעכן אינסטיטוט (ייִוואָ) אין ווילנע.

דער באַרימטער ייִדישער שפּראַכפֿאָרשער מאַקס ווײַנרײַך האָט אָנגערופֿן ייִדיש אַדער באַרימטער ייִדישער פּראַכפֿאָרשער מאַקס ווײַנרײַך האָט אָנגערופֿן ייִדיש אַ „שמעלצשפּראַך“, ד״ה אַ שפּראַך צונויפֿגעשמאָלצן פֿון אַנדערע שפּראַכן. וואָס באַטײַט דאָס? אפֿשר וועט אײַך נישט זײַן קיין חידוש, אַז ס׳רובֿ מאָדערנע שפּראַכן שטאַמען פֿון אַנדערע, וואָס מע רופֿט זיי אין דער לינגוויסטיק „רויוואַרגשפּראַכן“. למשל, ענגליש שטאֵַמט פֿון די רויוואַרגשפּראַכן אַנגלאָסאַקסיש, אַלט־סקאַנדינאַוויש, פֿראַנצייזיש און לאַטײַן (מיט אַ צוגאָב ווערטער געליִענע פֿון אַנדערע לשונות, אַפֿילו ייִדיש און העברעיִש). ענגליש זעט נישט אויס ווי אַ שמעלצשפּראַך אין די אויגן פֿון ענגליש־רעדערס וואָס זענען נישט באַוווּסטזיניק פֿונעם אָפּשטאַם פֿון די ווערטער.

אין דעם פּרט איז אונדזער מאַמע־לשון ענלעך צו ענגליש. די הויפּטקאָמפּאָנענטן פֿון ייִדיש נעמען זיך פֿון די רויוואַרגשפּראַכן דײַטשיש, לשון־קודש (= העברעיִש) און עטלעכע סלאַווישע לשונות דער הויפּט פּויליש און אוקראַיִניש (רוסיש האָט געהאַט אַ קלענערע השפּעה). חוץ דעם איז גאַנץ גרינג צו דערקענען פֿון וואָסער לשון ס׳שטאַמט אַ ייִדיש וואָרט.

דאָ הייבן מיר אָן צו זען דעם חילוק צווישן ייִדיש און ענגליש. ייִדיש־רעדערס זענען בדרך־כּלל געווען צוויי־ צי סך־שפּראַכיק; אַ שטייגער, האָבן נישט אַלע ייִדיש־רעדערס געקענט פּויליש, אָבער זיי האָבן געקערט וויסן וואָסערע ווערטער ס׳נעמען זיך פֿון פּויליש צי פֿון דײַטש צי לשון־קודש. גאָר פּשוט: ענגליש־רעדערס האָבן געוווינט צווישן איינשפּראַכיקע ענגליש־רעדערס, בשעת ייִדן זענען אַלע מאָל געווען אַרומגערינגלט פֿון אַנדערע פֿעלקער—למשל, דײַטשן, פּאָליאַקן צי אונגערן. און אין אַ געוויסן שפּראַכיק־קולטורעלן אַרום האָבן ייִדן אַרויסגעהויבן דעם לשון־קודש־שטאַמיקן וואָקאַבולאַר צי דעם סלאַוויש־שטאַמיקן. האָבן זיי בדרך־כּלל געוווּסט, אַז זיי רעדן אַ שמעלצשפּראַך (כאָטש דעם טערמין האָבן זיי אַוודאי נישט געקענט).

אינעווייניקסטע צוויישפּראַכיקייט: מאַמע־לשון און לשון־קודש

אינעווייניקסטע צוויישפּראַכיקייט בײַ מיזרח־אייראָפּעיִשע ייִדן פֿאַררופֿט זיך אויף צוויי ייִדישע שפּראַכן וואָס האָבן דערגאַנצט איינע די צווייטע זייער באַניץ. אין תּוך אַרײַן איז לשון־קודש געווען די עיקרדיקע געשריבענע שפּראַך, בשעת ייִדיש, די וואָכעדיקע שפּראַך, איז געווען די גערעדטע. לשון־קודש איז פֿאַררעכנט געוואָרן פֿאַר דער מענערישער שפּראַך, ווײַל מענער האָבן געקענט לערנען, בשעת זייער ווייניק פֿרויען האָבן געהאַט די געלעגנהייט עס צו לערנען פֿאָרמעל. נאָר אַזאַ דיכאָטאָמיע גיט נישט איבער די רעאַליטעט. אַוודאי איז לשון־קודש געווען דאָס לשון פֿונעם סידור, פֿון דער תּורה און פֿון דער מישנה, דהײַנו, ס׳לשון פֿון לערנען. ייִדיש האָט, אָבער, דאָ אויך געשפּילט אַ ראָלע: דעם זעלבן בריוו אָדער שאלות־ותּשובֿות וואָס אַ למדן האָט אָנגעשריבן אויף לשון־קודש פֿלעג ער איבערגעבן בעל־פּה אויף ייִדיש. מע האָט געלייענט די הייליקע טעקסטן אויף לשון־קודש, אָבער וויכּוחים האָט מען געפֿירט אויף ייִדיש. חסידישע רביים האָבן דערציילט מעשׂיות און געלערנט מיט זייערע חסידים אויף ייִדיש. כאָטש בלויז אַ קליינע צאָל פֿרויען האָבן זיך ויסגעלערנט לשון־קודש, זענען ס׳רובֿ מענער אויך נישט געווען קיין לומדים, נאָר געקענט בלויז גענוג לשון־קודש אויף צו קענען דאַווענען. תּפֿילות אויף מאַמע־לשון (תּחינות) און פֿאַרטײַטשן פֿונעם חומש (אַ שטייגער, „צאנה־וראינה“) האָבן אין דער אמתן געלייענט סײַ פֿרויען, סײַ מענער. ייִדיש האָט מען אויך געהערט אַפֿילו בײַ רעליגיעזע צערעמאָניעס: בײַ אַ חתונה האָט דער בדחן משׂמח געווען דעם עולם אויף ייִדיש און מע האָט געזונגען אויף ייִדיש; פּורים־שפּילן האָט מען געפֿירט אויף ייִדיש. לשון־קודש איז טאַקע געווען דאָס לשון פֿון דאַווענען און זײַנע ווערטער און אידיאָמען זענען אַרײַנגעדרונגען אין ייִדיש, נאָר אין אַ סבֿיבֿה וווּ צווישן דעם רעליגיעזן מאָמענט און דעם וועלטלעכן איז נישט געווען קיין קלאָרע גרענעץ, האָט ייִדיש און ייִדישקייט געשפּילט אַ ראָלע אומעטום.

דרויסנדיקע סך־שפּראַכיקייט

מיר האָבן פֿריִער דערמאָנט, אַז ייִדיש־רעדערס האָבן געוווּסט וועגן די רויוואַרגשפּראַכן, ווײַל זיי האָבן אָפֿט געוווינט צווישן רעדערס פֿון יענע שפּראַכן. ס׳רובֿ ייִדן האָבן גערעדט, אָבער נישט געלייענט, די אָ נישט־ייִדישע לשונות. אַ שטייגער, האָט אַ וואַרשעווער ייִד אין 19 טן י״ה אפֿשר געקענט גענוג פּויליש צו פֿירן געשעפֿטן מיט זײַנע נישט־ייִדישע שכנים, אַ ביסל דײַטש צו קענען זיך צונויפֿרעדן אויף די לײַפּציקער ירידן און אויך אַ ביסל רוסיש (די מלוכה־שפּראַך) צו קענען רעדן מיט מלוכישע באַאַמטע. ייִדן האָבן געשפּילט די ראָלע פֿון עקאָנאָמישע פֿאַרבינדלערס צווישן פֿאַרשיידענע פֿעלקער, איז דאָס קענען עטלעכע שפּראַכן געווען נייטיק און נוצלעך. ייִדן מיט וועלטלעכער דערציִונג האָבן גוט 1549 ), אַ געבוירענער אין ־ געקענט פֿרעמדע שפּראַכן. נעמט, למשל, אליהו בחור ( 1469 דײַטשלאַנד געוווינט און געאַרבעט אין איטאַליע. ער איז געווען אַ לערער פֿון לשון־קודש מיט אַ רוימיש־קאַטוילישן קאַרדינאַל; אָנגעשריבן אַ גראַמאַטיק פֿון לשון־קודש; צונויפֿגעשטעלט אַ לאַטײַניש־דײַטשיש־לשון־קודש־ייִדיש ווערטערבוך; און געשריבן פּאָעזיע אויף ייִדיש. זײַן באַקאַנטסט ווערק איז דאָס „בבֿא־בוך”, אַ פּאָעמע אַדאַפּטירט פֿון אַן איטאַליענישער מעשׂה (וואָס דאָס איז געווען אַדאַפּטירט פֿון אַן ענגליש ביכל)!

פּונקט ווי מיט אַנדערע שפּראַכן, האָט ייִדיש אויסגעפֿילט די ראָלע פֿון אַ מין געזעלשאַפֿטלעכער מחיצה: דאָס רעדן מאַמע־לשון האָט פֿאַרהיט קודם־כּל שפּראַכיקע אַסימילאַציע און במילא קולטורעלע און געזעלשאַפֿטלעכע אַסימילאַציע. ייִדן האָבן געשאַפֿן אַן אייגענע קולטור אויף ייִדיש, אָבער דאָס שעפּן פֿון די אַרומיקע לשונות האָט אויך צוגעטראַָגן צום אויפֿבלי פֿון דער ייִדישער קולטור. אין מיזרח־אייראָפּע האָבן ייִדן געהאַט אַן אייגענע שפּראַך און קולטור, און דאָס האָט זיי געגעבן די מעגלעכקייט צו שעפּן בײַ אַנדערע—און גלײַכצײַטיק בלײַבן גאַנץ מיט זיך אַליין.

.avif)

.avif)