Hand drawn maps as remembrance practice: Moshe Kleinhendlers memories of his home shtetl, Khmielnik

Hand-drawn maps in yizker bikher

In Tel Aviv, in the late 1950s, a group of Holocaust survivors from the tiny Polish town of Khmielnik assembled a yizker bukh a memory book documenting their home shtetl. They delivered photographs, submitted texts covering history of the local Jewish community, wrote up short studies of the local schools, political parties, religious organizations, charity funds, folklore, and stories of famous individuals who had lived in Khmielnik, as well as obituaries memorializing the ones who had perished during the Holocaust.

In this way an archive was created, one that was based on documents and materials concerning people, places, events, and social initiatives from a past that would otherwise be lost. Starting as early as the 1940s and through the 1960s and 1970s, more than 600 such yizker bikher were compiled by landsmanshafts Holocaust survivor communal organizations centered on a given city or town from the regions of present-day Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus.

Published mainly in Israel and the United States, yizker bikher were the survivors response to the Nazi pursuit of wiping out Jewish communities and erasing traces of their culture, along with any knowledge of the Jewish presence in the pre-war Europe. These books aimed at retaining collective memories of perished kahals and supporting the site- and community- oriented identity of the Jewish survivors displaced after the Holocaust.

In addition to texts, documents, photographs, and obituaries yizker bikher often included hand-drawn maps that provided images of historical places whose appearance and social structure had been changed as a result of World War II and the Holocaust. These sketches differ from professional cartographic designs and represent a wide range of aesthetic approaches. Since their authors prioritized visualizing certain aspects of the mapped sites at the expense of accuracy, these maps are characterized by significant diversity, ranging from the purely fantastical to quite precise projections.

Although we might be used to approaching maps as scientific in nature and aimed at objectivity, it has been shown that in fact they are not neutral. Maps convey specific ideas regarding a certain space in terms of its physical structure and layout, social relationships, and economy. Maps are also to use the phrase proposed by Amy Griffin and Sbastien Caquard impregnated with all sorts of emotions. These emotions emerging from the relationship of the map makers toward the sites they depict can be seen in the maps visual appearance, as well as by specific wording and annotations that provoke emotional responses in their viewers. This emotional character of maps is particularly apparent in the case of hand drawn maps included in yizker bikher.

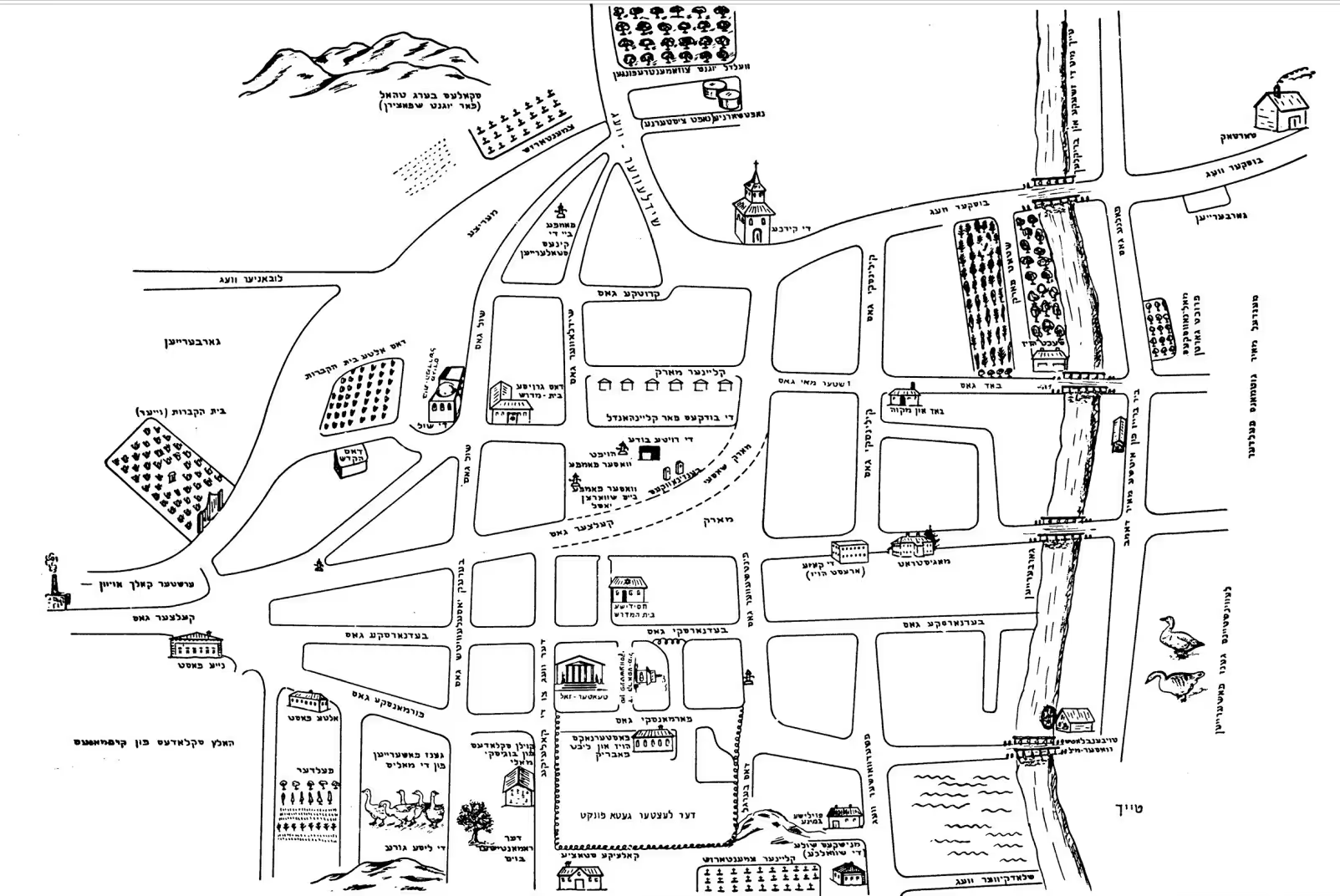

Moshe Kleinhendlers sketch of his home shtetl Khmielnik

Khmielnik yizker-bukh features a hand-drawn map created by Moshe (Moniek) Kleinhendler. Born in 1917, hewas one of five children of Chaya (née Becker) and Chaim. The family occupied a house at 3 Furmańska Street, not far from the main market square. Moshe – like his grandfather, father and brothers – worked as a locksmith. During the war, together with other members of the family, he was sent to the Buchenwald camp. He was released in January 1945 when the camp was liberated. After the war the family decided to leave Poland. Eventually in 1949 Moshe along with his parents, his wife Sarah and their baby daughter Varda settled down in Israel. Moshe with his father opened a workshop in Jaffa where they built machines for making candles.

In the late 1950s Moshe Kleinhendler got involved in the yizker-bukh project for Khmielnik. Although he did not undergo any professional cartographical training, he had an outstanding imagination and good memory for details. Kleinhendlers daughter Varda remembers her father spending several evenings at the kitchen table re-creating the topography of pre-war Khmielnik from his memories and imagination.

Similarly to other Jewish survivors who experienced war-time exile, traumatizing conditions of the Nazi camps, and the hardships of post-war migration, Kleinhendler drew his map in Israel, which had become his new homeland. Far away from Khmielnik and without any hope for returning, all that he had left were memories, which he referred to when drawing his map.

Kleinhendler depicted the spatial structure of pre-war Khmielnik by adding elements of the local architecture. The sketch does not show the whole urban development of the town. It can be assumed that only those objects that the author recognized as particularly important to illustrate economic, social, and cultural life of the community are depicted. Therefore, the town hall is shown, the seat of the commune office, a cinema, two post offices, a city jail, a railway station, synagogues, a parish church, four cemeteries (two Jewish and two Christian), and a ritual bath.

There is a marketplace in the center of the map with small drawings depicting shopping stalls, a well, a water-pump, the ice cream parlor, and a petrol station. Tanneries, goose feedlots, mills, coal and wood depots, a soap factory, a sawmill, and a brewery illustrate local economic life. Kleinhendler also added elements representing the natural landscape, such as the nearby hills, the river, parks, gardens, and farmlands on the outskirts. Each of these objects were annotated in Yiddish, which was the everyday language of the Jewish community.

Moshe Kleinhendler’s map of Khmielnik (Poland), after: Khmielnik [Chmielnik] yizker book in The New York Public Library Digital Collections last accessed 13 January 2023.

The presence of the expressive elements included by Kleinhendler in his map raise a number of questions about how the map should be approached as a historical source and as an element of community-oriented post-Holocaust memory practice, however. Several questions might be posed regarding the intentions behind the inclusion of specific sites and objects as well as the specific aesthetic choices.

Why did Kleinhendler rotate the map, situating north on the left side? Was it a mistake or did he perhaps intend to show the space of the town from some specific perspective? Why did Kleinhendler inscribe in the very fabric of the spatial layout of pre-war Khmielnik images of selected natural forms (such as the river) and particular buildings, and omit others?

Did he include these objects to materialize and substantiate the map in a specific way, or perhaps to give the drawing more personal character? Did Kleinhendler include any details that function as decorative insertions or to invoke bucolic images of his hometown? Is an image of smoke coming from a sawmill chimney an actual memory of the mapmaker, or an emotive addition?

If it was added, what purpose did it serve? Why did Kleinhendler introduce the fence marking the 1942 last ghetto area into what was a purely pre-war shtetl full of life and movement? Did he intend to evoke any specific values or ideas that he considered crucial for the depiction of the identity of members of the local Jewish community and to transmit this identity after the Holocaust in the yizker-bukh?

Do any of those elements refer directly to Kleinhendlers biography or to the history of his family? Did the mapmaker have any personal experiences associated with Jewish youth-meetings in the forest shown on the eastern outskirts of the town, did he participate in the trips to the mountains located north of Khmielnik, did he meet his loved one under the romance tree? Did Kleinhendler enjoy watching movies in the cinema, or perhaps he preferred theater performances more? Was eating ice cream from the parlor situated on the market place a part of his leisure experience?

Or perhaps he included this building as a recognizable landmark, believing that it would bring back memories of joyful, happy moments among the Khmielnik dwellers? Although some of these questions cannot be answered without referring to biographical sources, such as written memories or oral testimonies, Kleinhendlers sketch included in Khmielnik yizker-bukh encourages contemporary viewers to reflect not only on the documentary and historical value of the drawing but most of all on how this sketch reveals on a visual level the personal content, intimacy, and emotions as well as specific meanings that are not immediately obvious to outsiders.

The map of Khmielnik: intimacy, emotion, and post-Holocaust memory

Kleinhendlers map illustrates Khmielnik in the peak of its pre-war prosperity. Both the aesthetic form and the visual content of the drawing as well as numerous annotations included in the map indicate the authors close attachment to specific qualities of his home-shtetl. The precise grid of lines marking the course of individual streets within the towns space creates a design whose elegant structure offers the viewer some sense of order.

This image of Khmielnik as a well-organized town whose Jewish population constituted about 82 % of towns inhabitants before 1939, seems to oppose the Nazi antisemitic ideology that linked Jews with chaos and dirt. Kleinhendler presented the spatial outline of pre-war Khmielnik with a high degree of accuracy, including almost every route, naming both main streets and small alleys individually. He also introduced the roadways leading toward the surrounding towns and therefore embedded his shtetl in a wider geographical context of the region.

For the contemporary viewer it might almost seem as if the map maker wanted to catalogue and memorialize each of these streets, as if he considered each of them as equally important and performing a distinct function. When comparing Kleinhendlers drawing with a contemporary map of Khmielnik (and taking into consideration changes in the spatial outline that occurred over the last several decades), the viewer can observe high level of similarity. This comparison also reveals that Kleinhendler not always kept the accurate proportions and that he rotated the map. Contrary to one of the basic cartographic rules, he situated the north on the left side of the drawing instead of placing it on the top. Knowing however that the map-maker’s home was at Furmańska street (three blocks west from the main market square) and locating this site on the sketch, it can be assumed that Kleinhendler drew the map from the perspective of his own residence.

In imposing this perspective on the readers of the yizker-bukh, Kleinhendler revealed how personal and intimate his relationship with the space of Khmielnik was. Careful examination of the sketch also reveals that the map maker combined three different types of the space projection. Kleinhendler introduced three-dimensional objects drawn either in an overhead perspective (as observed from a top of hill) or in a natural perspective (as watched within the space of the town, by a human located on the ground level) into the grid of individual streets depicted in horizontal perspective (as in a vertical aerial photograph). Combining these perspectives allowed him to include within one drawing extensive information regarding the spatial structure and architecture of the town, keeping at the same time his personal approach toward particular buildings and sites.

Kleinhendler gave each of these small drawings a form of highly elaborated visualizations. He communicated his attachment and pride in his home shtetl by putting a lot of effort in the depictions of architectural structure such as the shapes of windows, the types of roofs, and the forms of the facades. Kleinhendler revealed his attitude toward the multiethnic and multireligious character of pre-war Khmielnik by depicting buildings hosting municipal institutions (the town hall, a commune office), objects essential for Gentiles (a church, Christian cemeteries), and for Jews (the main synagogue, Hasidic synagogue, praying houses, mikveh, funeral house and Jewish cemeteries).

Visualizing all the buildings with a parallel level of attention, he communicated the idea of a balance in local social relations. Thus, the map is the visual memorialization of Khmielnik as a place inhabited by different ethnic and religious groups, a town that had a rich cultural heritage, and that was embedded in the wider geography of the region. The intimate, personal character of the sketch is also revealed by the nature of Kleinhendlers written annotations in Yiddish.

He labeled not only main streets and significant buildings but also utilitarian facilities, garden areas, fields, single trees, and rock formations. In these annotations he used the everyday language of the local community, introducing customary names of places and objects. Within the area of the market square Kleinhendler drew a miniaturized image of a water-pump that he described as the Black Josls. Next to the pump he drew a small kiosk captioned as a red shack, the first ice cream parlor in the town.

Drawing industrial factories, plants, fields, and gardens that brought income to the towns residents, Kleinhendlers captions reveal the original functions of each building along with the names of their owners: Tojbenblats water mill, Lewensteins goose feedlot, Malinowskis garden, Mendel Mayer Gutmans fields,“coal depot run by Bugajski and Mały.”Kleinhendler represented the local nature with colorful names, including: a “bald mountain,” “the little hill,” “the little forest where young people met,” and “hills where the youth strolled.” A single tree stands not far from Kleinhendlers family house and is labeled a romantic tree, suggesting that it was a place of lovers trysts. These names, which would sound familiar to the residents of pre-war Khmielnik, reveal not only Kleinhendlers detailed awareness of the local topography and his familiarity with other members of the community but also his knowledge of local customs and ways of living.

All these details included in the map in a visual form are intense expressions of map makers intimate relationships toward the depicted objects. The result is not only an image of the vibrant social life of the pre-war Jewish community, but also of Kleinhendlers personal sense of place and even some elements of his own biography. From the memories of Kleinhandlers daughter Varda we learn that the romantic tree was actually the place where her father dated Sarah the love of his life and his future wife.

Along with spatial structure and architecture of pre-war Khmielnik Kleinhendler chose to include an element created only in 1942, when the members of Jewish community suffered under Nazi occupation. By depicting the fence of the last ghetto (located near the train station) the map maker used visual means of expression to mark the genocidal outcomes of the war time period.

Conclusion

Kleinhendlers map offers a complex visual narrative that expresses his individual spatial experiences, intimate relationship with his hometown, his unique knowledge, as well as the emotions, meanings, and values he assigned to the mapped space in general as well as to particular sites and objects within it. Focusing on buildings he considered important to the local community as a whole, Kleinhendler used the drawing to communicate his cohesive sense of historical and cultural identity. Moreover, the manner in which the visualization was constructed reveals the map makers individual approach toward a map as a memory tool.

Engaging in the yizker-bukh project and drawing the map at his kitchen table, Kleinhendler put himself in a position of a creative agent who aimed at the symbolical recovery of the image of the shtetl from the erasure that was attempted by the Nazis. Thus, his map becomes an element of a memory practice focused on re-building post-Holocaust identity among the survivors. While specific elements visualized on the map like image of smoke coming from a sawmill chimney may have existed only in Kleinhendlers imagination, once published in the yizker bukh it helped to create a space for Kleinhendler himself and for all the community members to cope with loss, longing and grief, reviving at the same time their identity as “Khmielnikers”.

.avif)

.avif)