Bilgoraj

Biłgoraj Jews making ropes - Unknown

Shtetl of Commerce

A medieval village near Lublin, Bilgoraj's Jewish community developed during the late-16th century. It distinguished itself by its productive commerce and industry, and through the major literary figures it birthed. A small community, with 3,486 Jews out of a total of 5,311 in 1897, Jewish Bilgoraj made a more lasting impression than its numbers would suggest was possible.

A survivor reminisced:

"In the middle of the town was the marketplace, surrounded on all four sides by Jewish homes and shops, where the Jewish merchants stood with their businesses waiting for customers…Next to the shops would sit the Jewish women merchants with various good fruits …"

Thursday was market day for Bilgoraj and all manner of merchants and shoppers descended on the marketsquare to make the week's purchases.

Strangely enough, one of the shtetl's most important products was the sieve. Beginning in the 19th century, as modern industrial production invaded the Polish landscape, the Jews of Bilgoraj who already had skills as craftsmen and traders established a vital center for the manufacture, processing, and export of sieves to markets in Hungary, Russia, and Germany. Though a few businessmen made decent fortunes from the sieve industry, the great majority of Jews remained poor factory workers, many of them concentrated around the Yiddish world of Brik-gas (Bridge Street) in the center of town.

In 1909, the Kronenberg family established a major printing company, producing volumes of Hebrew and Yiddish works - both religious and secular - for export into the surrounding communities. In 1927, a publishing house was added in order to distribute the works of prominent rabbis.

Following World War I, when poverty and economic hardship were the orders of the day, resilient and resourceful Jews regrouped and focused their efforts on textiles (largely horsehair weaving) and a new lumber industry, establishing two sawmills in the forests outside of town. During the same period Bilgoraj's Jews, as with other Jewish communities, organized many welfare services, mutual aid societies, interest-free loan guilds, and three Jewish banks in order to meet the needs of the shtetl.

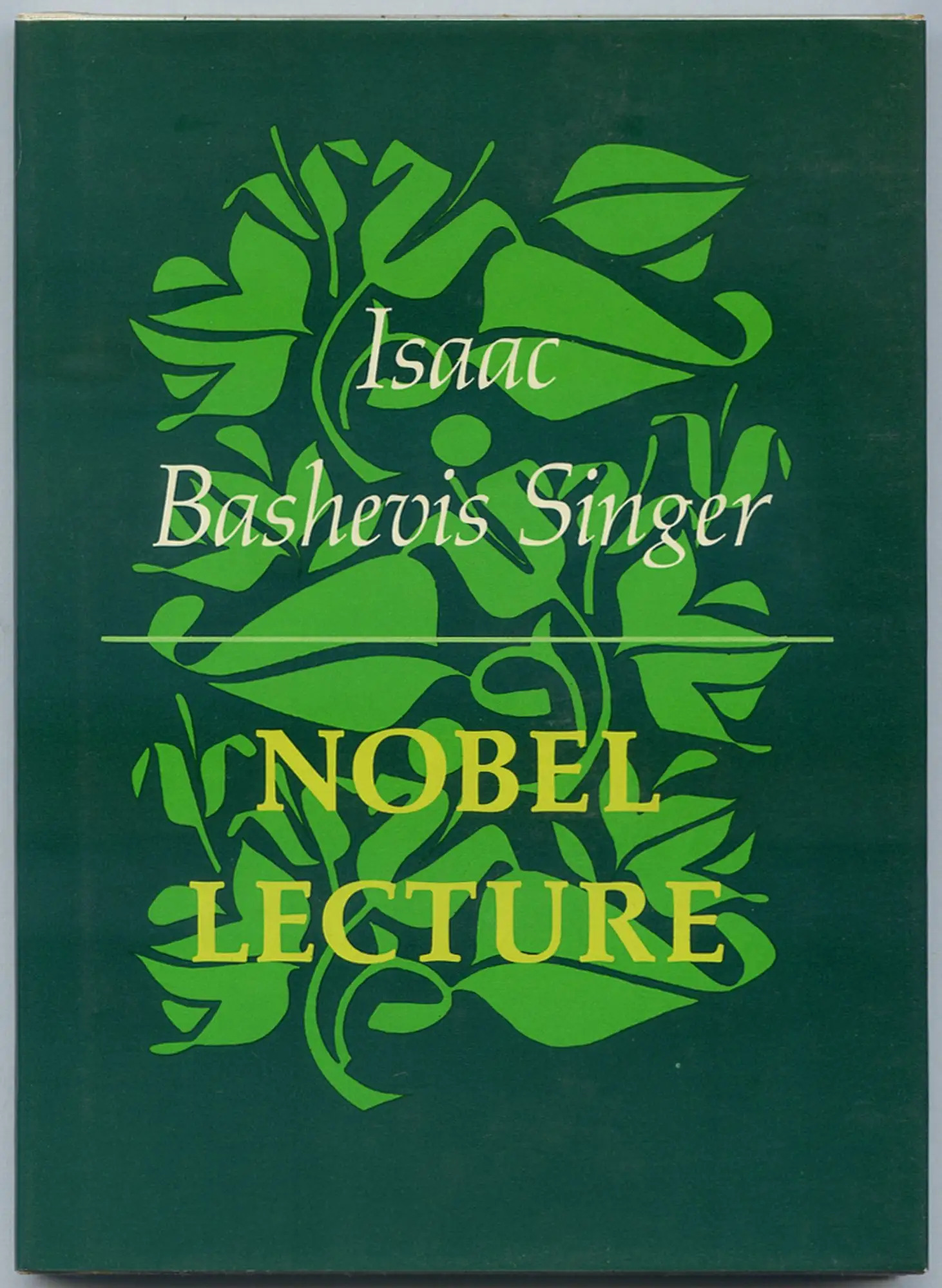

Is Yiddish a dying language? A ghostly insight...

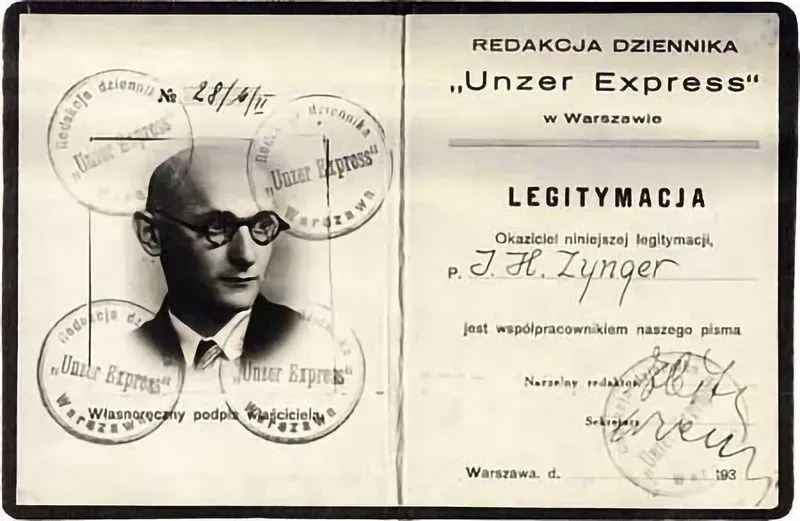

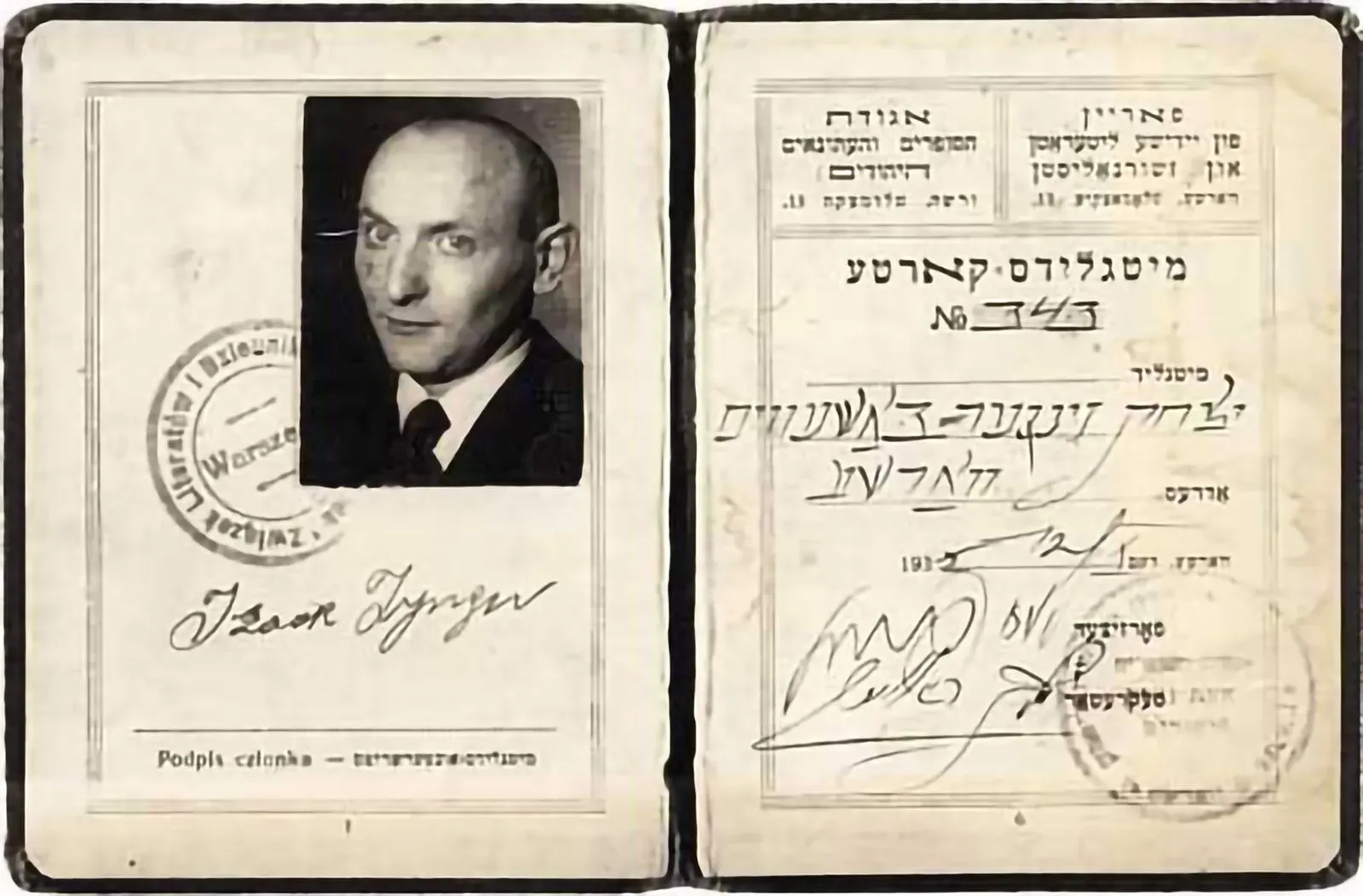

l.B. Singer won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978. During his short speech at the banquet. he clarified for the world his literary mission; "People ask me often, 'Why do you write in a

dying language?' And I want to explain it in a few words. Firstly, I like to write ghost stories and nothing fits a ghost better than a dying language. The deader the language the more alive is

the ghost. Ghosts love Yiddish and as far as I know, they all speak it. Secondly, not only do I believe in ghosts. but also in resurrection. I am sure that millions of Yiddish speaking corpses will rise from their graves one day and their first question will be: 'Is there any new Yiddish book to read?' For them Yiddish will not be dead,"

.avif)