קול פֿון יוגנט

דאסָ אויפוואַקסן קומט מיט אַ סך שווערע באַשלוסן

וואָו קען איך זיך אַרײַנפּאַסן? זאָל איך פֿאָלגן מײַנע טאַטע־מאמע און מײַנע לערערס צי גיכער מײַנע חברים? צי זאָל איך גאָר אַליין אויסקלײַבן אַן אייגענעם דרך? וואָס איז דער עיקר פֿון מײַן לעבן? און וואָס וועט זײַן אין דער צוקונפֿט?

אין דער ייִדישער טראַדיציע ווערט דער טראָפּ געלייגט שטענדיק נאָכצוגיין אין די דרכים און וועלטבאַנעם פֿון די עלטערע דורות—דאָס לערנען ייִדישע טעקסטן—חומש, גמרא, רש״י אאַז״וו—אַלע מאָל געווען דער אָנגענומענער אופן צו געפֿינען דעם באַטײַט פֿון דעם לעבן. אין צווישנמלחמהדיקער אייראָפּע האָבן די יונגע ייִדישע דורות אויסגעדריקט נײַע אידעען, וואָס דערפֿון זענען אַרויסגעוואַקסן נײַע ברירות אין ייִדישן לעבן. פֿון דעם צונויפגיסן אַלטע און נײַע געדאַנקען האָבן אויפגעבליט אַ ריי נײַע פּאָליטישע באַוועגונגען. פֿאַר יונגוואַרג האָט דאָס געמיינט אַ ריי נײַע מינים דערציִונג און שפּעטער נײַע אַקטיוויטעטן וואָס ייִדישע קינדער האָבן ביז דעמאָלט נישט געקענט. ס׳האָט זיך געפֿילט ווי אַ נײַע וועלט, מיט נײַע מעגלעכקייטן, וואָס מע האָט געדאַרפֿט איבער זיי אַרבעטן כּדי זיי צו פֿאַרווירקלעכן. דאָס האָט געגעבן די יונגע דורות דעם כּוח צו חלומען און אַפֿילו רעאַליזירן די חלומות.

פֿון ק״חדר צו דער שול; פֿון מלמד צום לערער

ווען מע קוקט אָן שול־פֿאָטאָגראַפֿיעס פֿון ייִנגלעך און מיידלעך פֿון די 1920ער אָדער 1930ער יאָרן, זעען זייערע פֿריזורן און מלבושים אפֿשר אונדז אויס מאָדנע. אַז מע קוקט זיך אָבער גוט צו צו זייערע פּנימער, דערזעט מען די זעלבע סאָרט טיפּן וואָס מע טרעפֿט אין אַ הײַנטיקן קלאסצימער: דער שטיפער, דער פֿאַרחלומטער, דער פֿלײַסיקער און נאָך אַנדערע. אין יענער צײַט האָט מען זיך גענומען ספֿקן ווי דאַרף מען אויסשולן ייִדישע קינדער; אויף דער פֿראַגע זענען אויפגעקומען נײַע ענטפֿערס. ווי אַ רעאַקציע אויף סאָציאַלע פּראָצעסן פֿון די 1920ער יאָרן האָט מען געשאַפֿן אַ גאַנצע גאַמע פּריוואַטע שולנעצן מיט אַ כּוונה אויסצופאָרעמען די קינדער אויף אַ נײַעם אופן. אַ שטעטל וואָס האָט אַ מאָל געהאַט בלויז איין לערן־אָרט, האָט געקענט פֿאָרלייגן פֿיר אָדער פֿינעף ברירות, יעדע איינע מיט פֿאַרשיידנאַרטיקע פּאָליטישע און סאָציאַלע האָריזאָנטן.

טאַטע־מאמעס וואָס האָבן זיך געקענט פֿאַרגינען צאָלן שׂכר־לימוד, האָבן געשיקט זייערע קינדער אין שולן וואָס האָבן אָפּגעשפּיגלט זייערע אידעאָלאָגיעס; און דאָס האָט במילא משפּיע געווען אויפן שפּעטערדיקן פּאָליטישן צוגאַנג פֿון די קינדער.

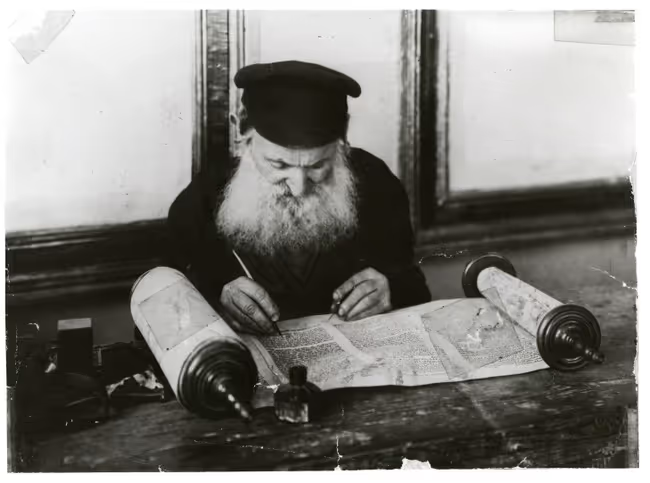

אַ סך קינדער פֿלעגן זיך אָנהייבן לערנען צו דרײַ ביז פֿינעף יאָר אינעם טראַדיציאָנעלן חדר, וואָס פֿלעגט זיך געפֿינען אין איין צימער בײַם מלמד אין דער היים. צי פֿון דער היים האָבן די קינדער שוין געקענט דעם אַלף־בית צי נישט, איז דער חדר מיטן מלמד געווען דער יסוד פֿון דעם לערנען. (ניגונים האָבן געהאָלפֿן בײַם לערנען דעם אַלף־בית: „קמץ אַלף אָ, קמץ בית בָ, קמץ גימל גָ…“.) ס׳זענען אויך געווען תּלמוד־תּורות אויסגעהאַלטענע פֿון דער קהילה פֿאַר אָרעמע קינדער. אַ סך עלטערע קינדער, אפֿשר 60%, פֿלעגן אַריבער אין מלוכישע שולן אָן שׂכר־לימוד, וווּ די לערנשפּראַך איז געווען פּויליש. טייל פֿון די שולן האָט מען גערופֿן „שאַבאסובווקאַ“ שולן ספּעציעל פֿאַר ייִדישע קינדער, וווּ שבת זענען נישט פֿאָרגעקומען קיין לעקציעס. אין אָט די שולן האָט מען אָפֿט פֿאַרווערט ייִדיש—מע האָט געלייגט דעם טראָפּ אויף אויסלערנען די קינדער רעדן פּויליש.

די פֿאַרשיידנקייט פֿון ייִדישע טאָגשולן אין פּוילישע שטעט אין די 1920ער און 1930ער יאָרן, האָט נישט קיין גלײַכן הײַנט, אַפֿילו אין גרויסע שטעט, אַזוי ווי ניו־יאָרק און מאָנטרעאָל, מיט אַ גאר גרויסער ייִדישער באַפֿעלקערונג. אַגבֿ, די הײַנטיקע ייִדישע טאָגשולן, וואָס האָבן אַ מאָל דאָרט געבליט, ווי אויך אין מעקסיקע און אין בוענאס־אײַרעס, האָבן זיך אָפּגעזאָגט פֿון ייִדיש ווי די לערנשפּראַך.

אין פּוילן זענען די גרעסטע שולנעצן געפֿירט געוואָרן פֿון: תּרבות, צישאָ, יבנֿה און אגודת־ישׂראל. תּרבות (טײַטש ׳קולטור׳ אויף עברֿית) האָט געלערנט עברֿית און ציוניזם. די צישאָ (צענטראַלע ייִדישע שול־אָרגאַניזאַציע) איז געווען אַן אָרגאַן פֿון דעם ייִדישן אַרבעטער־בונד; אין די שולן האָט מען געלערנט אויף ייִדיש און געשטיצט די היגע ייִדישע קולטור. יבנֿה איז געווען מער טראַדיציאָנעל פֿרום, אָבער אויך ציוניסטיש. אגודת־ישׂראל האָט אָנגעפֿירט די חורבֿ־שולן פֿאַר ייִנגלעך און די בית־יעקבֿ־שולן פֿאַר מיידלעך; דאָס זענען געווען די פּאָפּולערסטע בײַ אָרטאָדאָקסישע משפּחות. נאָך די קלאסן האָבן זיך קינדער געקענט באַטייליקן אין כּלערליי נאָכמיטאָגדיקע אַקטיוויטעטן, אַ שטייגער שפּילן פֿידל און פּיאַנע אָדער לערנען זיך פֿרעמדע שפּראַכן, בתנאַי, אַז טאַטע־מאמע האָבן געקענט צאָלן שׂכר־לימוד. טייל קינדער האָבן אַפֿילו געלערנט גמרא בײַ אַ פּריוואַטן רבין.

ייִדיש יונגוואַרג: צוקונפֿט און חלומות

לאָמיר דורכטראכטן דאָס וואָס מע דערוואַרט פֿון אַ הײַנטיקן 16־יאָריקן. ס׳רובֿ צילן זענען יחידישע: זיך פֿלײַסיק לערנען, מע זאָל אָנגענומען ווערן אין אַ גוטן אוניווערסיטעט, היטן זיך נישט אַרײַנפֿאַלן מיט חבריה וואָס נוצט נאַרקאָטיק און אַנדערע שלעכטע דרכים. אין יענער צײַט, אָבער, האָבן יונגע ייִדן נישט נאָר געהאַט אין זינען יחידישע צילן, נאָר אויך דעם ייִדישן כּלל. זיי האָבן זיך נישט בלויז געגרייט צו גיין אין אוניווערסיטעט. די וואָס האָבן געוואָלט אויספֿירן דעם ציוניסטישן חלום האָבן זיך געגרייט איבערצולאָזן די משפּחה און די היימישע סבֿיבֿה כּדי זיך צו באַזעצן אין אַ נאָך נישט אויפגעקומענער מלוכה. אַנדערע האָבן זיך אײַנגעשטעלט פֿאַרן אַרבעטער־קלאַס בײַם צושטיין צו פּראָפֿעסיאָנעלע פֿאַראיינען. דאָס געפֿיל פֿון שליחות האָט שטאַרק פֿאַראייניקט די באַטייליקטע אין די באַוועגונגען. בײַם צענערלינג איז נישט געווען קיין אָפּגרונט צווישן די פֿירערס און נאָכגייערס; זיי האָבן אַלע צוזאַמען געאַרבעט פֿאַר דעם ציל.

„כ׳האָב אָנגעהויבן ערנסט טראכטן וועגן צוויי ענינים: וואָס צו טאָן מיט זיך אַליין און צו וואָסער פּאָליטישער אָרגאַניזאַציע צושטיין“, האָט געשריבן דער צוואַנציק־יאָריקער לודוויק שטאָקעל וועגן זײַנע באַשלוסן אין די 1930ער יאָרן. דאָס צושטיין צו אַ באַוועגונג איז אָפֿט געווען דער ערשטער אומאָפּהענגיקער באַשלוס בײַ אַ יונגן מענטש; דאָס האָט זיך געקענט אַרויסווײַזן פֿאַר אַ סך וויכטיקער ווי מע האָט זיך אויסגעמאָלט. אין וואָסער שול טאַטע־מאמעס האָבן געשיקט זייערע קינדער—למשל, תּרבות, צישאָ צי בית־יעקבֿ—האָט בדרך־כּלל געהאַט אַ השפּעה אויף דער באַוועגונג וואָס די קינדער וועלן שפּעטער אויסקלײַבן. אַ מאָל האָט אַ גאַנצער קלאַס פֿון אַ מיטלשול פֿון תּרבות אויפגעשטעלט אַן אָפּצווייג פֿון השומר הצעיר. אָבער ס׳האָט זיך אויך געטראָפֿן, אַז מע האָט אויסגעקליבן באַוועגונג צוליב פּשוטערע סיבות: כּדי צו זײַן צוזאַמען מיט חברים אָדער קרובים צי כּדי צו ניצן די ביבליאָטעק אָדער צוליב אַן אַרויספֿאַר מיט דער גרופּע. אַזוי צי אַזוי: ס׳האָבן די איבערלעבונגען שטאַרק געביטן דאָס לעבן פֿון דעם דאָזיקן יונגוואַרג.

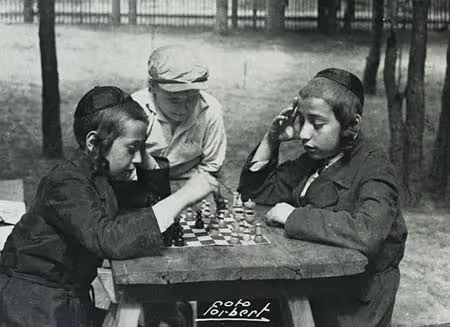

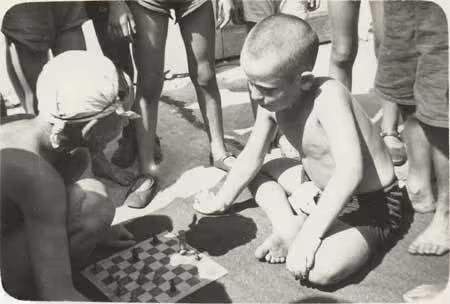

די ציוניסטישע גרופּעס האָבן געלערנט עברֿית און אָרגאַניזירט הכשרות, ד״ה, צוגעגרייט יונגוואַרג פֿאַר ערדאַרבעט אָדער אַרבעטן אין פֿאַבריקן. די הכשרות זענען געווען אַקטיוו איבער גאַנץ פּוילן און דײַטשלאַנד. די שטאָטישע יוגנט האָט געלעבט אין קיבוצים אויפן דאָרף און זיך געטיילט מיט אַלץ. מע האָט געזונגען חלוצישע לידער, אַ גאַנצן זומער געאַרבעט פֿון באַגינען ביז אויף דער נאָכט, אַפֿילו אין משך פֿון אַ פּאָר יאָר, האָבן זיי זיך צוגעגרייט צו לעבן אין די נײַע קיבוצים אין ארץ־ישראל. זייערע לאָזונגען זענען געווען שטאָלצע: „די הכשרות זענען אויסדריקלעך שווער, אָבער זייער תוכן איז וווּנדערלעך“. מע פֿלעג זיך וויצלען, אַז די קיבוצניקעס האָבן געלעבט פֿון „לופֿט און ליבע“.

מיט דער שטאַרקער השפּעה פֿון די איבערלעבונגען—אַפֿילו אויב נישט געשטרעבט עולה צו זײַן קיין ארץ־ישראל—איז יעדע באַוועגונג געווען אַן נײַער אויפקום אין אַ וועלט פֿון בײַטונגען. צי מע האָט זיך פֿאַראנומען מיט פּאָליטישע אַרעסטאַנטן צי מיט פֿאָרלאַנגען העכערע שׂכירות צי מיט לערנען העברעיִש אָדער ייִדיש מיט דערוואַקסענע צי גאָר עפּעס אַנדערש, האָט מען געאַרבעט לטובת־הכּלל. אַז מע רעדט וועגן אַ הײַנטיקער ייִדישער יוגנט־גרופּע דאָ אין אַמעריקע, שטעלט מען זיך פֿאר יוגנט וואָס פֿאַרברענגט צוזאַמען, טוען וווילטעטיקע אַרבעט און חסד־פּראָגראַמען, אַפֿשר לערנען אַ ביסל תורה, פֿאָרן אין זומער־פּראָגראַמען דאָ אָדער אַפֿילו אין ישראל. די ייִדישע יוגנט־באַוועגונגען פֿון פֿאַרן חורבן זענען געווען אַרײַנגעטאָן מיט לײַב און לעבן אין די אַקטיוויטעטן, אָבער זיי האָבן זיך פֿאַראנומען מיט אַ סך־אַ סך מער; מיט אַזאַ ברייטן פֿאַרנעם האָבן זיי אָרגאַניזירט און אָנגעפֿירט מיט פּובליקאַציעס, ביבליאָטעקן, לעקציעס, פֿירלייענונגען, פּאָליטישע רעדעס און דעמאָנסטראציעס, אוונטקורסן, ספּאָרט, קאָנצערטן, כאָרן, טעאַטער־גרופּעס, עקסקורסיעס און אַפֿילו געלט שאַפֿן פֿאַר צדקה־אָרגאַניזאציעס און פֿאַר די אייגענע אַקטיוויטעטן.

בר־מיצווה

פֿאַר מערסטע ייִדישע קינדער האָט דאָס ווערן דרײַצן יאָר אַלט געברענגט מיט זיך אַ סך נײַע אַחריותן. בײַם פּראַווען אַ בר־מיצווה אין שול ווערט דאָס קינד פֿאַררעכנט שוין פֿאַר אַ דערוואַקסענעם גלײַך ווען מע רופֿט אים אויף צום ערשטן מאָל צו דער תורה. אַזוי ווי ס׳רובֿ האָבן געלערנט תורה און לשון־קודש פֿון זייער אַ פריען עלטער, האָט דאָס ווערן בר־מיצווה נישט געפֿאָדערט די צוגרייטונג וואָס מיר קענען בײַם הײַנטיקן טאָג. מע האָט אויך נישט געמאַכט פֿון דעם אַזאַ גרויסע שמחה ווי ס׳פֿירט זיך הײַנט: ס׳רובֿ משפּחות האָבן זיך נישט געקענט פֿאַרגינען פּראַווען טײַערע מסיבות. ס׳איז געווען בלויז אַן איבערגאַנג־צערעמאָניע. קינדער פֿון דעם אַרבעטער־קלאַס—דער גרויסער רובֿ—האָבן צו דרײַצן יאָר געמוזט אָנהייבן העלפֿן מיט פּרנסה. דער זיבעטער קלאַס איז געווען דער סוף פֿון דער אָפֿיציעלער אָבליגאַטאָרישער דערציאונג פֿאַר קינדער אין פּוילן. מערסטע קינדער האָבן געמוזט אויפהערן גיין אין דער געוויינטלעכער שול כּדי זיך לערנען אין אַ פאַכשול אָדער ווערן אַ לערן־ייִנגל בײַ אַ מײַסטער. האָבן זיי זיך אויסגעלערנט נייען אָדער סטאָליערײַ און אַזוי אַרום אַרויסגעהאָלפֿן בײַם אויסהאַלטן די משפּחה. אַרײַנצוגיין לערנען ווײַטער אין אַ גימנאַזיע אָדער העכערע שולע איז געווען זייער שווער, ווײַל ס׳איז געווען באַגרענעצט דורך קוואָטעס שייך צו ייִדן. אַרײַנצוגיין נאָך דער גימנאַזיע אין אוניווערסיטעט איז נאָך שווערער געווען, און אויך באַגרענעצט.

ליבע און בענקשאַפֿט

צי יונגוואַרג האָט געאַרבעט צי ממשיך געווען דאָס לערנען אין אַ ישיבה אָדער אַ גימנאַזיע, האָט זיך בײַ זיי באַוויזן אַ נײַער פעֿנאָמען, וואָס אַ דאַנק דעם וועלן זיי קענען איבערמאַכן זייער געזעלשאַפֿט. בשעת זיי האָבן געלייענט נײַע ליטעראַטור און זיך צוגעהערט צו די שמועסן פֿון דעם עלטערן דור, האָבן זיי אָרגאַניזירט יוגנט־גרופּעס וווּ מע האָט צונויפגעלייגט כּוחות לטובֿת די באַוועגונגען וואָס האָבן זיך דעמאָלט געהאַלטן אין פֿאַרשפּרייטן איבער מיזרח־אייראָפּע, רוסלאַנד און דײַטשלאַנד. סך־הכּל האָבן זיך געשאַפֿן כּמעט הונדערט יוגנט־אָרגאַניזאציעס אין די 1920ער און 1930ער יאָרן, יעדע מיט אַן אייגענער פּראָגראַם. די אומגלייבלעכע פֿאַרשיידנקייט פֿון די אידעען האָט אָפּגעשפּיגלט ווי ברייט ס׳זענען געווען די גרויסע חלומות איבערצובויען די דעמאָלטיקע ייִדישער וועלט.

ס׳איז שווער מגזם צו זײַן די גרויסע השפּעה פֿון די יוגנט־אָרגאַניזאַציע אויף דער ייִדישער געשיכטע. אַ דאַנק זיי האָבן טויזנטער ייִדן עולה געווען און געהאָלפֿן אויפבויען מדינת־ישראל. זיי האָבן אויסגעפֿאָרעמט די קעמפּערס וואָס האָבן זיך בשעת דער צווייטער וועלט־מלחמה קעגנגעשטעלט די דײַטשן, זיי באַקעמפֿט פֿיזיש און אויך געראַטעוועט אַנדערע. פֿון זיי זענען אַרויס שפּעטערדיקע וויכטיקע מנהיגים אין ישראל און אין גלות אַזש ביזן איצטיקן יאָרהונדערט.

די יוגנט־גרופּעס האָבן מיט זיך פֿאָרגעשטעלט דעם גאַנצן פּאָליטישן ספּעקטרום. די אידעאָלאָגישע הויפּטריכטונגען אויף דער פּאָליטישער פּלאַטפֿאָרמע זענען געווען דער סאָציאַליזם, דער ציוניזם און דער טראַדיציאָנאַליזם. אָט די אידעאָלאָגיעס האָבן ייִדן קאמבינירט און דערמיט געשאַפֿן פּאָליטישע פּאַרטייען. למשל, פֿון דעם סאָציאַליזם מיטן ציוניזם זענען אויפגעקומען עטלעכע לינקע ציוניסטישע פּאַרטייען, וואָס זיי האָבן אַגיטירט לטובֿת אַ סאָציאַליסטישער ייִדישער מלוכה. פֿון דעם ציוניזם מיטן טראַדיציאָנאַליזם איז אויפגעקומען מזרחי, וואָס האָט געשטרעבט צו אַ ייִדישער מלוכה וווּ מע וועט זיך פֿירן לויט דער הלכה. סאָציאַליזם מיט דער אידעאָלאָגיע פֿון דאָיִקייט (קולטורעלע אויטאָנאָמיע אויפן אָרט) זענען געווען דער יסוד פֿון דעם בונד. דאָס מישן די אידעען און די המצאהדיקייט דערבײַ האָבן געמאַכט פֿון פּאָליטיק, פֿון די וועריאַנטן פֿון די אַלע אידעאָלאָגיעס, אַן עיקרדיקן טייל פֿון דעם טאָג־טעגלעכן לעבן. וואָסער פּאָליטישע פּראָגראַם מע זאָל נישט פּראָקלאַמירן, האָבן אַלע פּאַרטייען געהאַט אין זינען די צוקונפֿט פֿון דעם ייִדישן פֿאָלק. זיי האָבן עקסיסטירט אין אַ תקופה פֿון פּאָליטישער אַנגאַזשירטקייט וואָס האָט צו זיך נישט קיין גלײַכן אין דער ייִדישער געשיכטע. פֿון די פּאַרטייען זענען אויפגעקומען: בײַ די לינקע די צוקונפֿט, דער יוגנט־אָפּטייל פֿון דעם סאָציאַליסטישן בונד. מארָגנשטערן איז געווען די בונדישע ספּאָרטגרופּע פֿאַר קינדער און יונגוואַרג; דער סאָציאַליסטישער קינדער־פֿאַרבאַנד (סקיף). בײַ די סאָציאַליסטישע ציוניסטן זענען די גרעסטע גרופּעס געווען החלוץ און השומר הצעיר. אַנדערע ציוניסטישע גרופּעס—ווײַל ס׳האָבן זיך געשאַפֿן אַזוי פֿיל—גורדוניה, דרור און אַנדערע, מער אויף אַ קולטורעלן ווי אויף אַ פּאָליטישן יסוד. ס׳רובֿ ציוניסטישע גרופּעס האָבן געלייגט דעם טראָפּ אויף פֿיזישן כּוח און חלוצישער אַרבעט; זיי האָבן געשטרעבט זיך אומצוקערן צו אַ נאַטירלעכן לעבן־שטייגער, נאָענט צו ערדאַרבעט. ביתר איז געווען אַ רעכטע ציוניסטישע גרופּע. בני עקיבֿא איז געווען די רעליגיעזע ציוניסטישע גרופּע. צופים און מכּבי זענען געווען נישט פּאָליטיש געשטימט, נאָר גרופּעס וואָס האָבן זיך פֿאַרנומען מיט ספּאָרט.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)