To Eat or Not to Eat... That is a Jewish Question!

The subject of food is everywhere in Jewish culture. Food has always been an important part of our traditions. Think back to Adam and Eve, the story to begin all stories in the Torah. After God creates Man and Woman, he creates for them the Garden of Eden, instructing them:

"Of every tree of the Garden you may freely eat; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, you shall not eat of it"

This is the very first indication that there are some foods that you can eat, and others that you must not. This will then extend to become a more generic principle: there will always be some limits put upon human behavior.

Food has always meant more than just what we eat for lunch or dinner. Throughout history, we have assigned a very special meaning to the foods that we eat. Foods have been given religious significance, medicinal significance, and folkloric significance. We have 'comfort food', 'home remedies', and 'aphrodisiacs'. The choice "to eat or not to eat" is one that each of us confronts today. For example, someone may choose vegetarianism, deciding that the foods they eat in some way represent their compassion for animals, or even their political ideals. Observing the Jewish dietary laws - keeping kosher - is another way of positively determining what is acceptable or unacceptable as foodstuff. By looking at a group's food, we can learn about their values and their ethics.This information can offer us an opportunity to think about the purpose of the rules observed and the underlying principles on which they are based. Further, in Jewish tradition there is a code of behavior that accompanies what we eat and the meals that we prepare. Abraham, the father of this tradition, received three strange visitors to his home one night. The hospitality that he showed them by inviting them to sit at his table, sharing his bread and his meat with them, is instructive: we must know what to eat, but also who to eat with and how to share.

What is Jewish Food?

With Jewish communities spread all over the world, what exactly is Jewish food? When Sephardic Jews taste the well-known Ashkenazi "gefilte fish" (stuffed fish), often served at Passover, they comment on its tasteless quality. Their cuisine is known for sharper seasoning. But even among Ashkenazi Jews, gefilte fish has several styles: it can be salted or sweet, and it has entered the folklore as a delicacy. If Polish Jews and Iranian Jews, for instance, each have their own set of food customs, what common customs about food do different Jewish traditions share?

The basic food customs shared by traditional Jews the world over are centered on the Jewish dietary laws. Using these dietary laws as a base, Jews have embraced and adapted some of the foods native to their new lands. Using these they have created a new, distinctly Jewish cuisine, in every land where they settled.

Milchik, Fleyshik, and Pareve - Dairy, Meat, and Neutral - The Jewish Kitchen

The basic prohibition against mixing dairy products with meat products is derived through rabbinic interpretation. Why? This rule is derived from the statement in the Torah, "Thou shalt not cook a calf in its mother's milk". The ethical consciousness this rule brings is special. Even if the natural and animal worlds are made to serve humans, it is mandated that there should still be limits to rule Jewish behavior. Because of the exacting rules of kashres, the kosher Jewish kitchen contains many more cooking tools than the average kitchen, since separate meat and dairy dishes and utensils are required.

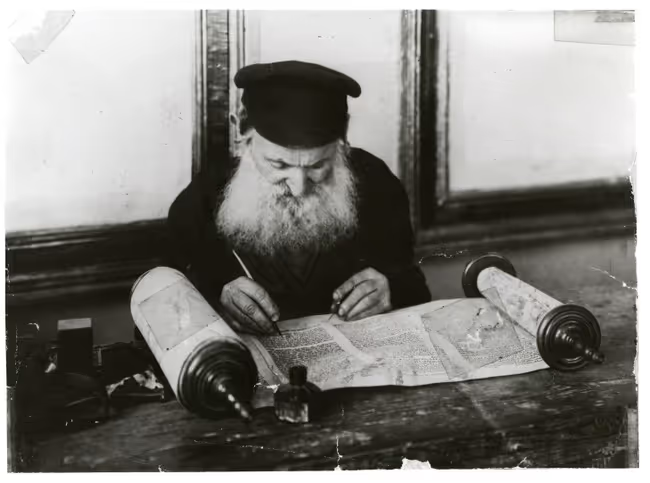

Shechitah - Laws Concerning Ritual Slaughter

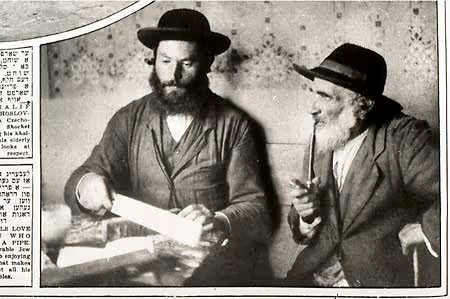

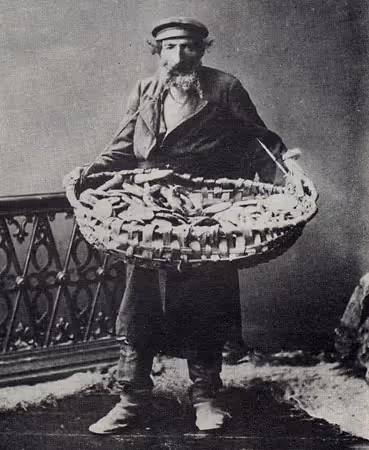

The slaughter of animals to be cooked for kosher food must be highly regulated. The slaughtering process starts with concern about the inspection of the animals, followed by the knives to be used. The laws of shechitah outline in specific detail exactly how an animal should be slaughtered in order to qualify as kosher. The specificity of the laws accounts for the emergence of a very important character in Jewish communal life: the shoychet. Jews, unlike their non-Jewish neighbors, could not themselves just pick a chicken from their yard to use to prepare a meal. Neither could they hunt an animal to kill and cook for a meal. Traditional Jews the world over depend on a shoychet to inspect all animals according to the extensive Jewish laws, to possess and properly maintain kosher knives. In these ways the shoychet renders meat kosher for the community.

From the Old Rules to the New "Cuisine" - Where a Jewish Meal Begins

Another familiar figure in the market was the kosher butcher, the katzef; but he had an altogether different image. The katzef was a simple salesman who handled the food. Responsibility for keeping food kosher continued at home, where the meat has to be salted and soaked in prescribed ways. Only after that process can the cooking begin. So, any kosher meat required a shoychet, as well as a housewife who knew how to keep the rules at home. Today, most of the salting and soaking is done at the butcher store, and the meat delivered ready to cook.

Shabes - The Seventh Day: Rest

Shabes (Yiddish), Shabbat (Hebrew), begins at sundown every Friday night, and continues through nightfall on Saturday. Commemorating the six days of divine creation, the seventh day was commanded as a day of rest. To keep within this spirit, no activity construed as "work" is accepted for the Sabbath. Definitions of "work" include, most significantly, food preparation, as it usually begins with the prohibitions against starting any fire (including electricity). The Sabbath's prayers and learning are organized around three meals (Friday night, Saturday afternoon and early evening- shaleshudes) all of which must be prepared before nightfall on Friday. The traditional Shabes foods emerged from creative exploration within these guidelines.

The Sabbath is the strongest, most distinct Jewish double pillar of ritual and folklore. This holy rest day evokes each week the creation of the world, and fosters a special consciousness expressed by sanctifying the foodstuff extracted from this created world. While detailed traditions around the Sabbath may have been forgotten by some, including the special Shabes meals, which are accompanied by blessings and songs, the spirit of the day has remained as a central tenet of Jewish tradition with its special food characteristics. The most central parts are:

Wine and Challah

First and foremost is the wine for the Kiddush (blessing, in Hebrew) and the challot - the two braided breads that grace every Shabes table. Jews took with them their tradition of using this ritual bread wherever they moved, and Poland was no exception. Often, the dough was kneaded on Thursday or very early on Friday, left to rise, and then baked before the Sabbath.

Tsholent

Tsholent (sometimes spelled cholent), the Sabbath stew, is representative of the Ashkenazi Shabes meal. It is a hearty, meaty stew prepared a day in advance and left to slow cook on a burner or in the oven overnight. The smell of the tsholent pot whetted the appetites of hungry Jews returning from synagogue prayers on Saturday afternoon.

Gefilte Fish

Gefilte fish (stuffed fish), perhaps the food most associated with Eastern European Jewry to this day, is also the traditional first dish of any Shabes or holiday meal. There is a tradition that festivities should be celebrated with "Boser v'dogim" (meat and fish, in Hebrew), food delicacies to mark the special day. The name, "stuffed fish", comes from the original preparation of the dish, which dates back to the Middle Ages in Germany. Chopped freshwater whitefish (usually carp or pike) was cooked and then stuffed back into the fish skin. Later, the skin was omitted and just the fish stuffing became the dish. Some Jews today continue to use carp, and stuff minced fish into the middle. There are many variations of the gefilte fish recipe: Polish Jews generally prepare it with a sugary taste, while the Lithuanians prefer it peppery. This distinction was the source of countless minor domestic disturbances, but most householdsstill would agree on serving gefilte fish with a healthy dose of khreyn, the grated horseradish-beet sauce.

Holidays and Holiday Meals

The cultural and religious organization of the Jewish year is marked by celebration and commemoration of many holidays, some religious and some historical. Traditional Jews observe this calendar, combining their formal communal prayers in the synagogue, with gatherings at home for special meals. Some holidays, like Passover (Peysekh, in Yiddish) and Succoth center more distinctly on meals, while others, like Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, rely more on the communal synagogue prayers. But each holiday has special foods associated with it.

Learn about the holidays listed below and the foods that accompany them:

Rosh Hashanah

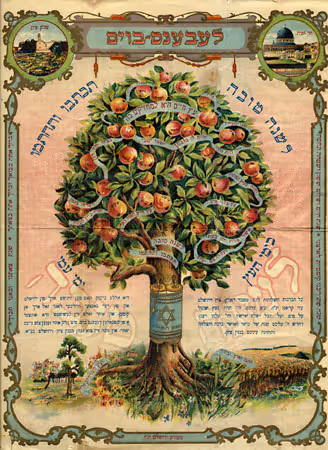

The New Year on the Jewish calendar is celebrated for two days in September or early October. The traditional foods of this holiday are symbolic of the qualities that are hoped for the oncoming year: sweetness, roundness, and fullness.

The Round Challah

The Rosh Hashanah challah is often round like a circle, with no beginning or end, much like the calendar year that has just ended and the new one that has just begun. It can also be braided like a ladder, to remind us that we should aspire to ascend to greater heights in the new year. This challah is usually baked with raisins, providing extra sweetness for a sweet new year. On the table there also will be honey, in which apples and the bread are dipped.

Tsimmes

One Rosh Hashanah dish particularly popular among Eastern European Jews is tsimmes, a sweet carrot stew. In addition to sweetness, the carrots here also symbolize reproduction, as mern, the Yiddish word for carrots, also shares that meaning. A typical recipe for tsimmes calls for the carrot to be sliced and cooked with honey or jam.

Fruits

The pomegranate, another Rosh Hashanah food symbol in addition to the apple. Its many seeds represent fertility, on the one hand, and, on the other, the 613 commandments of the Torah. Would you want to count the seeds to corroborate this?

Fish

In Eastern European Jewish tradition, fish are often cooked and served with the head intact, to symbolize the beginning of the coming year.

Succoth

The harvest festival of "booths", lasts eight days and usually falls at the end of October. Succoth is celebrated within a sukkah, the temporary dwelling built outside of one's home, where all meals are eaten. As a harvest festival, special significance is placed on all fruits and vegetables prepared and eaten in the sukkah.

Hannukah

Hannukah commemorates the victory of a relatively small group of Jews against a Hellenist army in Jerusalem in 165 BCE. This short-lived victory, considered by many to be a miracle, coincided with the rededication of the Holy Temple. Oily foods are common because those Jews who recovered the desecrated Holy Temple, found a small quantity of oil that lasted burning miraculously for eight days. The celebration of Hanukkah, therefore, lasts eight days and features the lighting of one new candle per night, until you are lighting eight together. The foods eaten on Hanukkah emphasize oil, recalling the miraculous oil of the Hanukkah story. Eastern European Jews eat latkes (potato pancakes), fried in oil. In Israel, the custom is to eat sufganiyot (deep-fried donuts).

Purim

A festive holiday, usually falling in March, which commemorates the saving of the Jews of Persia in antiquity. Slated for murder by Haman, one of the King's henchmen, the Jews were saved by the queen herself, Ester, a Jew, and her uncle Mordechai. Purim is a joyous holiday and is celebrated by the exchange of food gifts, shalakhmones (mishloah manot in Hebrew). The traditional meal at Purim is the only one in which wine is featured plentifully.

Hamentashn

These triangular pastries are most associated as an Eastern European Jewish food on Purim. The triangular shape is said to represent the hat worn by Haman in Ancient Persia. The pastries traditionally have a sweet poppy filling (mon, in Yiddish); and this play on words, Hamontoshn is likely the source of the name of the cookie.

דאָס ייִדישע עסן

עסן איז אין דער ייִדישער טראַדיציע דורכגעפֿלאָכטן מיט ריטואַל און באַטײַט. ס׳האָט זיך נאָך אָנגעהויבן מיט אָדמען און חוהן, די מעשׂה וואָס איז אַ יסוד פֿון אַלע מעשׂיות: נאָך דעם וואָס גאָט האָט באַשאַפֿן דעם מאַנספּאַרשוין מיט דער ווײַבספּאַרשוין האָט ער זיי געמאַכט דעם גן־עדן, און ער האָט אָדמען פֿאַרזאָגט:

„פֿון אַלע ביימער פֿון גאָרטן מעגסטו עסן; אָבער פֿונעם בוים פֿון וויסן גוטס און שלעכטס, פֿון אים זאָלסטו נישט עסן“.

דאָס איז דאָס ערשטע מאָל, וואָס טייל עסנוואַרג מעג מען עסן און אַנדערע נישט. אין דעם איז אַוודאי פֿאַראַן אַ העכערער פּרינציפּ: דער מענטשלעכער אויפֿפֿיר דאַרף האָבן אַ גרענעץ.

דאָס עסן האָט אַלע מאָל אַ ברייטערן באַטײַט ווי סתּם דאָס וואָס מע האָט צום מיטאָג אָדער צו דער וועטשערע. אין פֿאַרלויף פֿון דער געשיכטע האָט עסן געקראָגן אַ ספּעציעלן מיין; פֿאַרשיידענע מינים עסן האָבן באַקומען אַ רעליגיעזן באַטײַט, אַ מעדיציניש חשיבֿות און אַ פֿאָלקלאָריסטישן תּוכן. מיר האָבן מאכלים וואָס טרייסטן אונדז, וואָס זענען היימישע רפֿואות און ליבע־מיטלען. די ברירה „עסן אָדער נישט עסן“ שטייט פֿאַר אונדז ייִדן ביזן הײַנטיקן טאָג. למשל, איינער מעג ווערן אַ וועגעטאַריער און דורך דעם אַרויסווײַזן זײַן געפֿיל פֿון צער־בעלי־חיים אָדער זײַנע פּאָליטישע געדאַנקען. כּשרות איז אונדזער ייִדישער אופֿן צו דערקענען וואָס מע מעג און וואָס מע טאָר נישט עסן. לויט דעם וואָס אַ פֿאָלק עסט קען מען אַ סך דרינגען וועגן זײַנע עטישע ווערטן; דאָס גיט אונדז אַ געלעגנהייט צו באַטראַכטן דעם באַטײַט פֿון אָט די כּללים. ווײַטער איז דאָ אין דער ייִדישער טראַדיציע אַן אויפֿפֿיר־קאָדעקס וואָס גייט אין איינעם מיט דעם וואָס מיר עסן און וואָס מיר גרייטן צום עסן. אין אונדזער תּורה האָט אַבֿרהם אָבֿינו אײַנגעפֿירט די טראַדיציע, וווּ ער נעמט אויף אין אַ שיינער נאַכט דרײַ פֿרעמדע געסט. זײַן הכנסת־אורחים, דאָס וואָס ער פֿאַרבעט זיי צו עסן מיט אים בײַ איין טיש ווערט וויכטיק, און מע לערנט אונדז, אַז וואָס קען מען עסן, מיט וועמען און ווי אַזוי זיך צו טיילן מיטן עסן.

וואָס איז ייִדיש עסן?

אַזוי ווי ייִדן זענען צעזייט און צעשפּרייט איבער דער גאַנצער וועלט, ווי קען מען וויסן וואָס דאָס איז אַזוינס ייִדיש עסן? ווען אַ ספֿרדישער ייִד פֿאַרזוכט די באַקאַנטע אַשכּנזישע געפֿילטע פֿיש זאָגט ער באַלד, אַז זיי האָבן נישט קיין טעם; זײַנע מאכלים זענען שאַרפֿער. נאָר געפֿילטע פֿיש גרייט מען דאָך אויף פֿאַרשיידענע אופֿנים: מע באַווירצט מיט צוקער אָדער מיט פֿעפֿער; בײַ אַשכּנזים איז דאָס אַ דעליקאַטעס. אויב, אַ שטייגער, פּוילישע און פּערסישע ייִדן האָבן באַזונדערע קולינאַרע מינהגים, וואַָס זשע האָבן זיי בשותּפֿות? דער ענטפֿער איז כּשרות: וואָס עסט מען, ווען עסט מען עס, פֿאַר וואָס עסט מען עס, ווי גרייט מען עס צו, וואָס מישט מען נישט… עסן האָט אײַנגעוואָרצלט ייִדישע רוחניות. מיט כּשרות האָבן ייִדן אַדאָפּטירט, און אַדאַפּטירט, מאכלים פֿון די לענדער וווּ זיי האָבן זיך באַזעצט. אַ דאַנק דעם זענען אין יעדן לאַנד אויפֿגעקומען בפֿירוש ייִדישע מאכלים, וואָס ווי אַנדערש זיי זאָלן נישט זײַן טיילן זיי זיך מיט די געזעצן פֿון כּשרות .

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(Phone).avif)

.avif)