Lodz

.avif)

History and Settlement

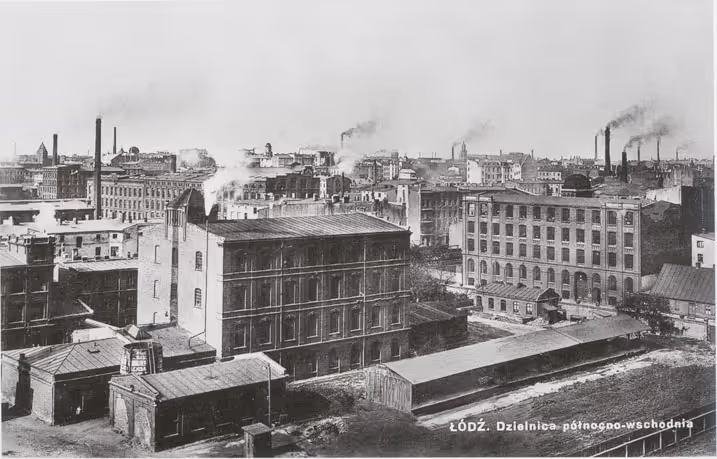

Grand palaces amidst dirty brick facades, crowded slums bisected by wide boulevards, smokestacks towering above cottages, a broad-shouldered industrial proletariat amongst a handful of millionaire capitalists Lodz was a city of great extremes: "An ocean of miseries and sorrows beneath a mountain of gold and opulence," as a former resident described the city. Lodz was Poland's industrial capital, nicknamed "the Polish Manchester," and it stood out in a country of quaint medieval towns and rural villages.

Dating from the 14th century, Lodz remained a small village for centuries and, therefore lacks the feudal history of most other Polish cities. Its most significant chapter began after 1820, when the newly formed, Russian-controlled Congress Poland decided to transform this sleepy village into an international center for textiles production and other industry. The Czarist government invited German weavers and textile experts to settle in Lodz and to create this new industry. As a result of the numbers of Jews following on the heels of these German settlers, the population of Lodz greatly increased and a new city grew seemingly overnight. The population grew from a few hundred people before 1820, to 500,000 in 1913. By 1939, Lodz's population had increased to 700,000; one third of which was Jewish.

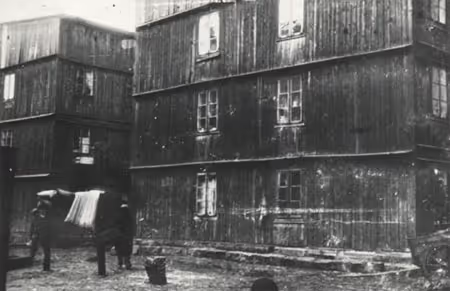

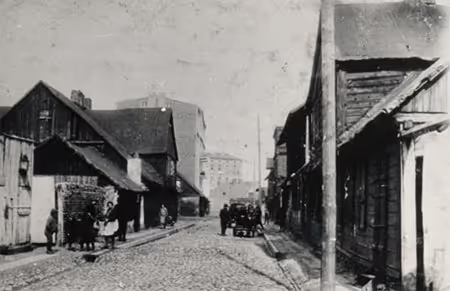

As Lodz became a major beacon for Jewish (and non-Jewish) workers across Europe, old hatreds and restrictions once again followed: Jews initially were confined to a small quarter near the old market square known as "Altshtot," (the old city). Because of the limits on settling in Lodz-proper, most Jews resided in the sister town of Baluty (long ago swallowed by Lodz's expansion), a working-class Jewish district encompassing factories, weavers, craftsmen, peddlers, as well as a few Jewish industrialists. Baluty, never really an affluent area, began a downward spiral during the interwar period (1919-1939). General unemployment after World War I, combined with mounting anti-Semitism, resulted in a largely disenfranchised Jewish population and terrible slum conditions.

Written accounts of both the industrial prosperity and the squalor in Lodz are legion; observers in the early 20th century were quick to note the disrepair of the city's fairly new buildings, the drunks, prostitutes, and generally unhealthful hygienic conditions. The poverty of the people was compounded by a landscape blighted by industrial pollution, with chemical waste pouring into the rivers, toxic drinking water, and foul-smelling sewage.

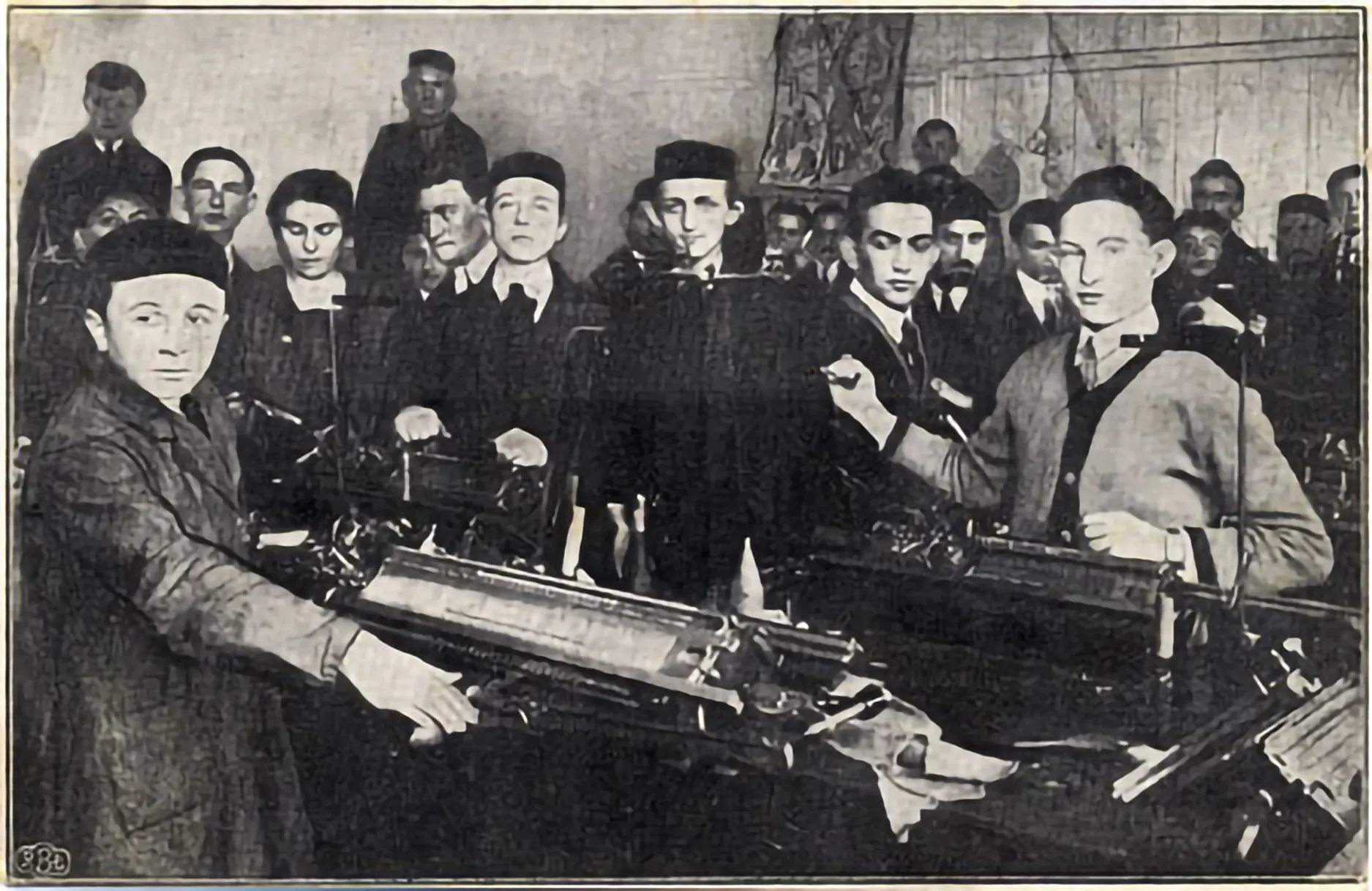

What really differentiated Lodz - and its Jews - from other Polish communities was its modern, industrial economy. Textiles were a mighty force that affected, directly and indirectly, the entire populace. And Jews played a prominent part in all levels of production, be it as industrial capitalists, wholesalers of raw materials, retailers, agents, brokers, or weavers. By 1914, 175 of the Lodz factories (33 percent) were owned by Jews; almost all of those were textile mills. Additionally, Jews owned thousands of small textile workshops, supplementing the city's impressive output of cotton, wool, linen, jute, hemp, and leather.

Institutions

Prior to 1918 a small kehilla functioned in a house near the town hall. Jews were obligated to adorn the walls with pictures of the Czarist royal family. The kehilla was controlled by an ebb and flow of coalitions of diverse Jews as it presided over basic administrative affairs such as community burials, welfare, and election of rabbis. Election of rabbis was reserved for those members of the community able to pay the voluntary community taxes. To further address the enormous need of the city's poor, a number of wealthy Jewish families banded together to establish philanthropic organizations, which provided a great array of services: Talmud Torah classes, vocational schooling, aid to the sick, orphanages, and relief during the holidays. A hospital, financed by the famed Poznanski family, served poor Jews in crowded and chaotic quarters; sick Jewish children were also sent to non-Jewish hospitals, at the expense of the community.

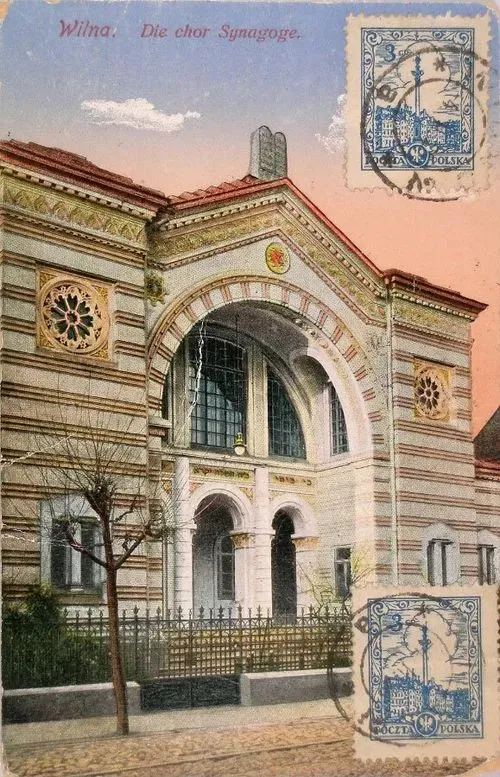

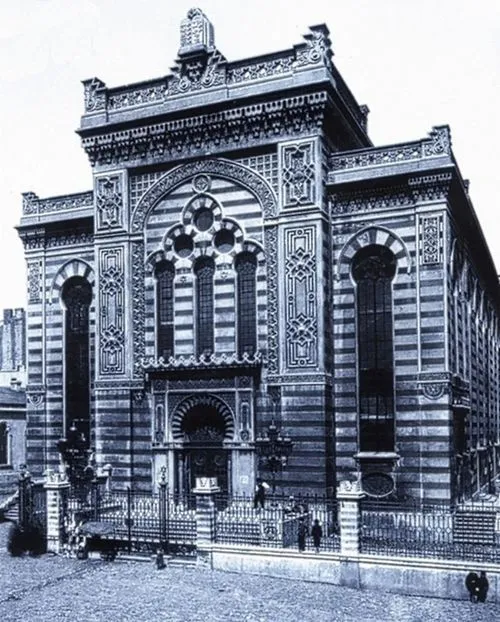

In Lodz, there were a number of synagogues great and small, Hasidic shtiblekh, mikvaot, two cemeteries (one of which was the largest Jewish cemetery in Europe), and a kosher slaughterhouse. The city's largest synagogue, completed in 1887, was the Great Synagogue on Kosciuszki Street - "The Synagogue on the Promenade" - a Conservative type congregation funded by a group of magnates headed by Izrael Poznanski. The synagogue was the largest building in the town center, a tremendous detailed Neo-Romanesque and Moorish structure featuring ornate mosaics and several domed towers. Another important synagogue was the Wolczanska Street Shul (completed in 1904), a Litvak congregation. As with many of Lodz's synagogues and Jewish communal buildings, both were methodically destroyed during the Nazi occupation.

While the secular industrialists of the city were few in number and disproportionately powerful, the Hasidim of Lodz were actually far more numerous. Split into various groups, the most established were the Ger and the Alexander Hasidim. These groups were perpetually involved in a struggle over control of the kehilla and local elections. The Ger Hasidim, generally wealthier and more powerful, formed a large part of the Agudat Israel party (a non-Zionist Orthodox party that often supported the government), and retained some of their influence through an alignment with non-religious Jews. The Alexander Hasidim found common interests with the non-Hasidic Jews (often called Litvaks for their association with the cultural enlightenment of Lithuania), who were divided into groups of secular Jews, Misnagdim (religious non-Hasidim), and, later on, Zionists.

In Lodz every variety of Jewish school existed. These included a yeshiva, a religious kheder, and a reformed kheder founded in 1890 for schooling in both religious and secular subjects. There was also a secular Jewish high school (the first Jewish gymnasium in Russia, a project directed in 1912 by the wealthy and progressive Rabbi Markus Braude, which featured classes in Polish and Hebrew), and a Yiddish school founded in 1918, as well as a number of vocational schools.

Arts and letters also flourished in Lodz, which was home to many well-known Jewish artists and bohemians, including pianist Arthur Rubinstein (1881-1982), author Jerzy Kosinski (1933-1991), and the Polish-speaking Julian Tuwim (1894-1963), one of Poland's greatest poets. There was a society of avant-garde artists called Yung-yidish and an active Yiddish theater scene in the years leading up to World War II. Several Jewish newspapers were published in the city, including the Yiddish papers Lodzer Togblat and Nayer Folksblat and Republika, (in Polish).

Textiles and Industry

Because the textile industry in Lodz was the main focus of Jewish economic activity to a great extent, many trade unions began to form early in the 20th century for textile workers, craftsmen, and industrialists, among the most prominent of which was the Union of Industrialists founded in 1912. As the labor revolution flared, the Bund, Zionists, and Polish Socialists all competed to unionize the city's abundance of workers. Though no group dominated disproportionately as was the case in some other cities,the Bund emerged as the most relevant force in unifying a divided Jewish proletariat. Formed in Vilna in October 1897, the Bund (The General Jewish Workers Bund of Poland and Russia - Lithuania was added to the name in 1900) was a bastion of strength for many within the large and embattled Jewish community, achieving the height of its influence in the late 1930s. The party created newspapers, organized youth groups and summer camps, set up welfare offices for the needy, apprised workers of their rights, fought anti-Semitism, and established numerous unions which consistently struggled for better conditions and wages for Jewish workers and an improved position vis-à-vis hostile Polish competitors.

As a counterpoint, one of the more interesting aspects of Lodz's great textile industry was the small but elite group of Jewish industrial magnates. In Lodz a capitalist class arose, generating fortunes, driving an industry that employed tens of thousands, and providing economic support for the Jewish community and the institutions and philanthropic organizations that sustained it.

Among the first of the Jewish industrialists was Abraham Prussak, who innovated Polish textiles by importing spinning machines from England, the center of the world's textile production. Markus Silberstein, Adolf Dobranicki, and others later brought many improvements but, among the list of Lodz's Jewish industrialists, the city's most successful and its greatest benefactor was, without a doubt, Izrael Poznanski (1833-1900).

Abraham Prussak was among the first of the Jewish industrialists, He brought innovation to the Polish textile industry by importing spinning machines from England, which was then the center of the world's textile production. Markus Silberstein, Adolf Dobranicki, and others later introduced other improvements. Among the list of Lodz's Jewish industrialists, the city's most successful and its greatest benefactor was, without a doubt, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznanski (1833-1900).

![Ignacy Płażewski, Pałac Izraela Kalmanowicza Poznańskiego przy ulicy Ogrodowej w Łodzi, I-4722-3" by Ignacy Płażewski, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA [version number 4.0]](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6891ffac7571e63c0e0f2860/6891ffac7571e63c0e0f292e_1024px-Ignacy_P%C5%82a%C5%BCewski%2C_Pa%C5%82ac_Izraela_Kalmanowicza.webp)

How did Izrael Poznanski help to shape Lodz?

With the help of his wife Eleonora Hertz's dowry. Poznanski was able to construct tremendous textile mills. warehouses, shops, a hospital. a synagogue, and Lodz's New Jewish Cemetery. His familial homes were as opulent and ostentatious as the slum was gritty. and they now house various Polish museums; his mausoleum is said to be the largest Jewish tombstone around. During a time of relative economic freedom and manageable political obstacles against Jews, Poznanski and his contemporaries thrived and molded not only the city of Lodz but an entire industrial infrastructure throu hout Poland. -

After World War I, when Eastern Europe's economy was in shambles, a highly nationalistic and anti-Semitic Poland resumed control of its former lands after the League of Nations created an independent Poland as part of the Versailles Treaty. Later, in the 1930s, the Polish government delivered a final blow to Jewish hopes of equal citizenship by adopting a systematic policy of economic anti-Semitism, refusing to aid Jewish businesses in their recovery. At the same time, hostility toward Jews began to manifest itself in wholesale efforts to squeeze Jews out of the textile industry at all levels. The Jewish community in Lodz, by the time the Nazis invaded Poland as World War II began, was already a shadow of its former self.

.avif)