History and Settlement

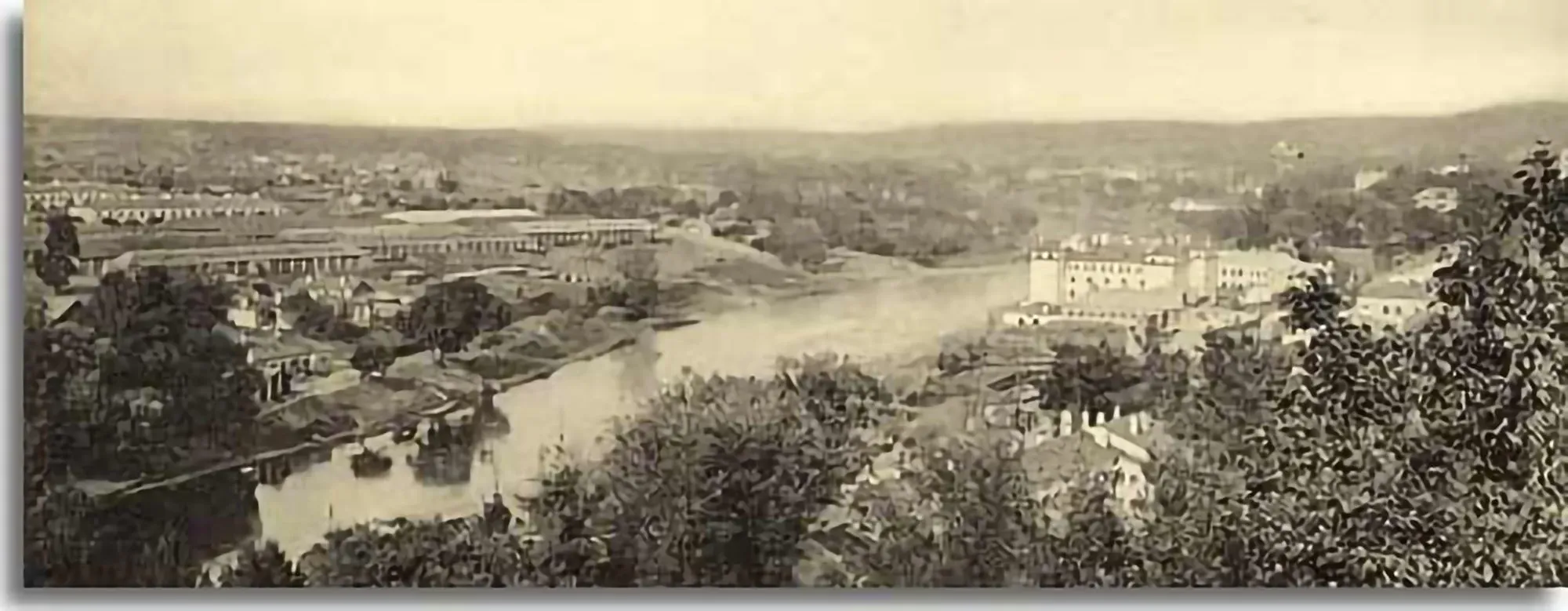

Known as the "Jerusalem of Lithuania," the city of Vilna was for centuries a giant among Jewish cities, the restless, dynamic center of Jewish intellectuals, scholars, Talmudists, political activists, artists, and writers. Relatively small in population, Vilna - and Lithuania in general - achieved prominence far out of proportion with its size. It was both a spiritual and secular capital for Ashkenazi Jews and it served as a bridge between the two worlds - old and new, traditional and modern, insular and universalist - until the community's near-complete destruction during World War II. Vilna was home of the Yiddish theater; it was the cradle of modern Hebrew, the language of the Bible and prayer. that found its way into the streets. It was the city of mystics, philosophers, and gangsters; it was a center for religious and secular learning. Vilna mixed the best and most sophisticated of many intellects, outlooks and philosophies.

The remarkable richness and cultural depth that existed - and thrived - in Lithuania did so despite the region's terrible and bloody history, one which never afforded the Jews security or stability, physically, politically, or otherwise. Lithuania's precarious geographic position between dueling empires and would-be conquerors rarely allowed for peace or stability. At different times over the centuries the city was captured and ransacked by invading Poles, Russians, Cossacks, and Swedes. For much of its history, violence and change were the norm.

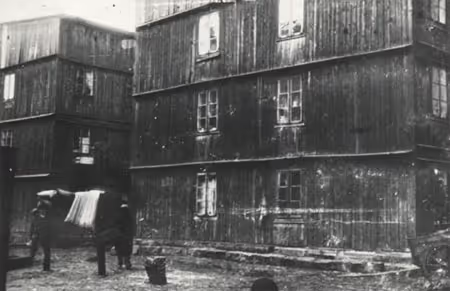

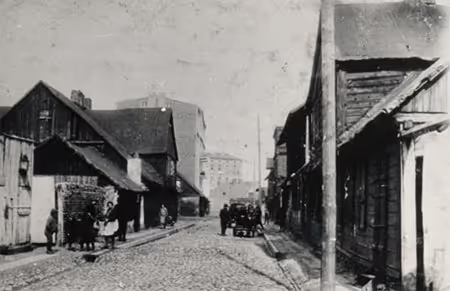

The city first appeared in the 10th century as a small Norman outpost amongst the swamps and forests. It did not gain importance until the 14th century, when it was made the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which later joined the expanding Polish empire to form a Commonwealth. There is evidence of an organized Jewish community during the mid-16th century, as Jews established modest institutions, which included a cemetery and a plain wooden synagogue. The usual array of peddlers, traders, craftsmen, and moneylenders congregated on Zydowska (Jew Street) and were bound to a tiny quarter within the cramped Old City. Despite a royal charter ostensibly assuring Jews the right to live and work within Vilna, resistance - both physical and legal - to the Jewish presence grew fiercer over time; Jews in Lithuania would consistently have to struggle against discriminatory laws and violence over the centuries.

Vilna's Jewish culture, which deepened and grew for 400 years, inspired the rest of the Ashkenazi world in ways that defy easy measure. This cultural powerhouse was perhaps the most thoroughly Jewish of European cities, with a community of about 75,000 people on the eve of the Holocaust, constituting an impressive 45 percent of the entire population. The crown of the long-developing civilization was abruptly and entirely destroyed during the war, when 87 percent of Lithuania's Jews were annihilated, and later, the Soviet regime bulldozed the remnants of much of the Jewish quarter. That regime also built a sports stadium on the land of the Old Jewish Cemetery.

Community Institutions

Vilna's kehile (Kehillah)had an illustrious history of heroic protection of the Jewish community, diplomatically championing the struggles for Jewish rights to live and work without restrictions and offering concrete forms of relief to the community during the worst days of famine, disease, and poverty. But the kehile was also an arena for ongoing political feuds between opposing camps of Hasidim, Mitnagdim, and wealthier secularists, each seeking to win the support of Vilna's Jews. In 1844, under Czarist authority, the kehile was abolished entirely and community administration fell to the Tzedaka G'dola (United Charities of Vilna), which oversaw taxation and later created a network of soup kitchens, hospitals, and free-loan associations (gmiles chesed).

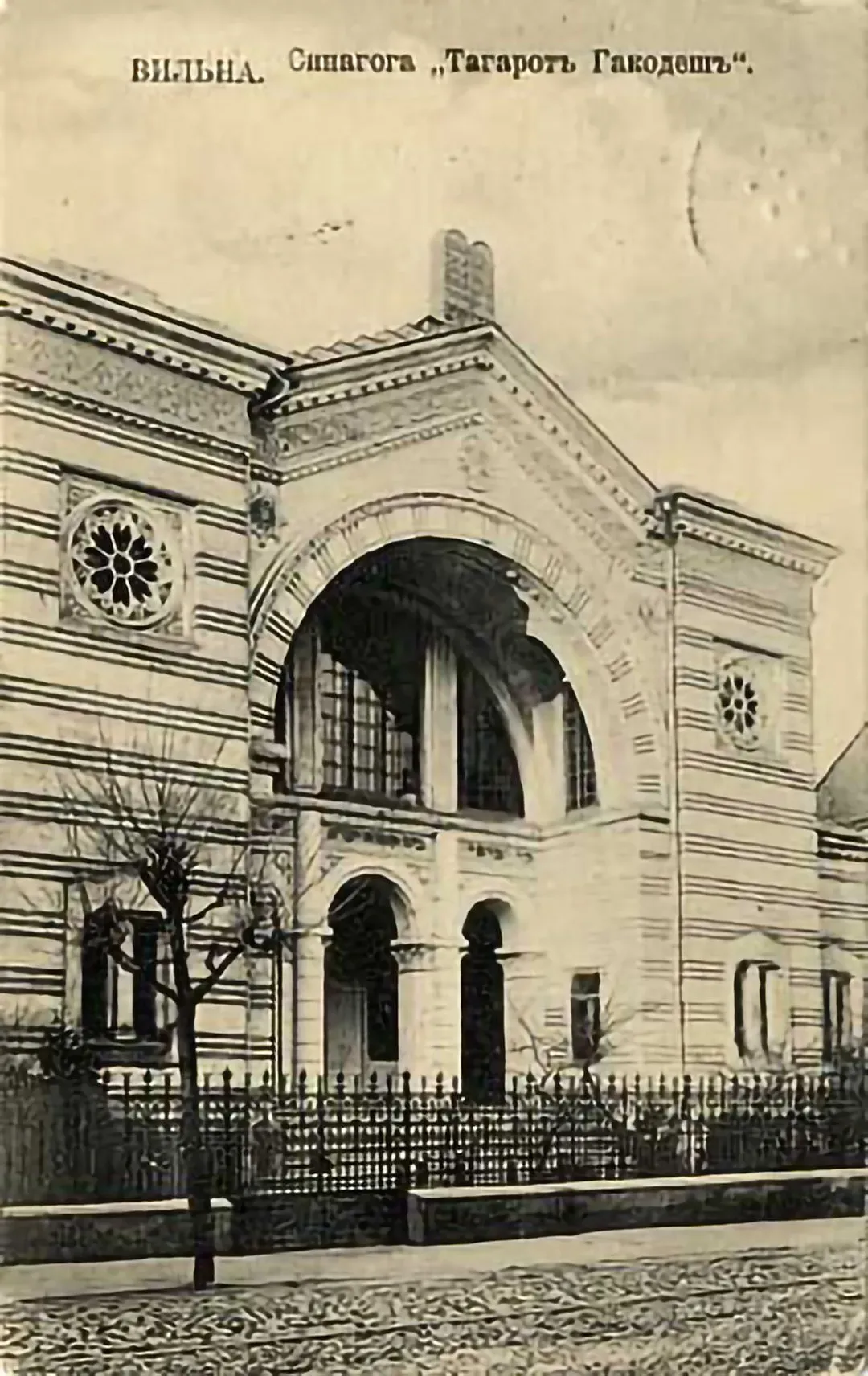

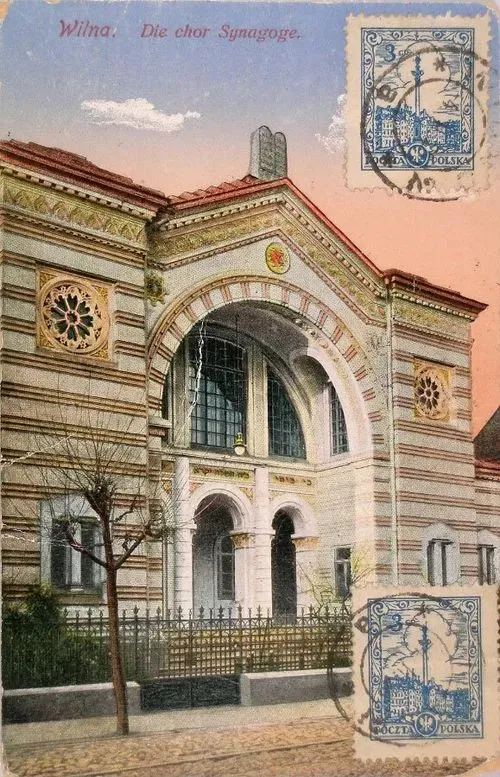

Of more than one hundred synagogues in Vilna during the years before the Holocaust, the Great Synagogue, an impressive edifice constructed during the early 17th century after Jews were permitted to build a stone structure to replace the original wooden one, was one of the most important. Located at the corner of Zydowska and Niemiecka (Jewish and German Streets), the synagogue and its large courtyard formed the nucleus of the city's Jewish community, both symbolically and geographically. The synagogue and the many smaller organizations contained within it were the central forum for Jewish life over the centuries, providing a physical base for cultural, political, and spiritual activity. Adjacent to the Great Synagogue, within an intricate labyrinth of alleyways and interconnected buildings were a Beis medresh , a mikvah, a great library, welfare organizations, the kehile offices, and numerous kloyzn (tiny prayer houses), often made up of members of trade-guilds...

Schools

Vilna was the Ashkenazi center of education, with the most sophisticated and variegated system of schooling for both secular and religious Jews. Vilna itself contained many of traditional khedorim for children and, as early as the 17th century, philanthropists established Talmudei Torah for the poorest of students. The region was also particularly well endowed with exceptional and famous yeshives, schools which were akin to colleges for the religious students and sages who attended them. Outstanding centers of thought and learning, the yeshives drew scholars and seekers from across the Jewish world, innovating new forms of Jewish observance and interpretation of ancient Jewish texts. So important and integral to the religious community were some of the schools that, like many secular organizations, they were evacuated out of the doom of World War II Europe to be reestablished in the safety of the New World.

Among the most famous of the yeshives was Etz Khayim (Tree of Life), better known as the Volozhin Yeshiva. It was a great center of learning established in the town of Volozhin by Rabbi Haim Volozhiner in 1803. Rabbi Volozhiner was a great admirer of the Gaon of Vilna's movement of Mitnagdim and he established the school as a means of enticing young students away from the growing wave of Hasidism. Following the Gaon's interpretation and outlook, Volozhiner ensured that students would read the texts for their basic and literal meanings in order to truly understand the context in which they were written. A regional center for study, the Volozhin became a model for other yeshives across Eastern Europe. Encompassing hundreds of students at its height, the yeshive successfully resisted the continuous demands of Maskilim and Russian authorities to introduce secular subjects and was only forced to close for a few years in the 1890s.

Encouraged by Volozhiner's success, Rabbi Nathan Zvi Finkel founded the Slobodka Yeshiva in 1882, in the Lithuanian town of the same name, near Kovno. Finkel was a proponent of the Musar movement, a strict school of Mitnagdim that called for devout and literal adherence to Jewish law, especially among young yeshive scholars. During disagreements in 1897 regarding how the school should be run, the yeshive split into two: Yeshiva Kneset Israel for those loyal to Rabbi Finkel's tradition, and Kneset Beit Yitzkhak for their opponents. Kneset Israel was popular and well respected, and it grew considerably during the first decades of the 20th century, at one point enrolling more than 500 students. It opened a sister school, the Hebron Yeshiva, in Hebron, Palestine in 1929. Following a massacre by local Arabs, this school relocated to Jerusalem. When the Slobodka School was finally forced to close by the Nazis in 1941, its few survivors regrouped. They eventually opened a new yeshive in Israel at Bnei Brak, near Tel Aviv.

As for the progressive and secularized world of Jewish education, Vilna was the center of great innovation. Modern, Russian-leaning schools developed during the mid-19th century and the Tsar's government even sponsored a Rabbinical seminary beginning in 1847, which later became a secular teachers' seminary. Soon, both Hebrew and Yiddish schools appeared and, by 1916, Vilna had 21 Yiddish schools (with 4,000 pupils) and six Hebrew schools (with 1,600 pupils), numbers that increased during the following decades. Also in 1916, Josef Epstein, a worldly physician, taught secular Jewish courses to students in his own apartment - in Hebrew - laying the foundation for the Hebrew Tarbut system of education. That system, which soon produced a formal Tarbut Hebrew school in Vilna, brought Epstein's curriculum of Hebrew and modern subjects forward onto a much larger stage- that of the entire Ashkenazi world. The movement to create a modern Hebrew culture soon became mainstream within Jewish communities from Bilgoraj to Buenos Aires to Baltimore, and developed alongside the Zionist struggle for a Hebrew homeland.

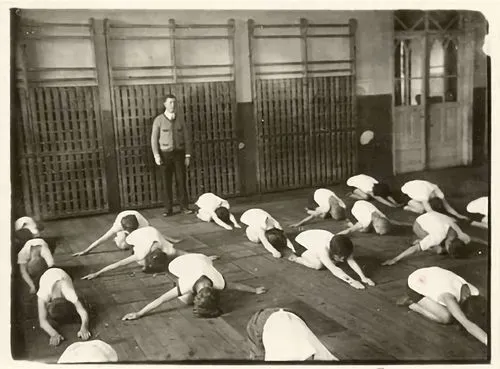

By the late-19th century, adults also had the option of studying in vocational schools, among the most famous of which were the Vilna Technicum and the Hilf Durch Arbeit (Help Through Work) trade school, both established by Jewish philanthropists. In a community strongly unsettled by the industrialization of the economy, students could learn modern craftsmanship, mechanical trades, plumbing, sewing, drawing, and bookkeeping, and other skills that could help them rise out of poverty and unemployment.

Religious Leaders

By far the most famous of all the city's scholars was Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, better known as the Gaon of Vilna. Born in 1720 to a long line of rabbis, the Gaon (a Hebrew term for genius) was renowned for his keen critical understanding of Jewish texts and his innovative methods of Talmudic commentary, methods which considerably influenced Jewish scholarship. The Gaon, well educated in mathematics and secular science, required such knowledge of his disciples, whose numbers continued to grow significantly late into his life. He was famous for being a fierce Mitnaged, transforming the Vilna of his lifetime into a bastion of Mitnagdim, and firmly opposing the rise of Hasidism, which was said to be stopped at the gates of the city. It was not until after the Gaon's death that the Hasidim, following a long and bitter struggle, managed to secure the right to congregate within Vilna's Jewish precincts. One of the Gaon's most important legacies was his early attempt at repopulating Palestine with Jews. Although he did not succeed himself, some of his most devout followers formed an early brigade of emigrants to the Holy Land, long ahead of the Zionist movement, which began in 1892 with the first Zionist Congress, and that would grip the Jewish world a century later.

Another important religious figure in Vilna was its Chief Rabbi, Isaac Rubinstein, who was brought to the city in 1909 from Crimea in order to serve in his new post. Rubinstein was a prodigious scholar, deeply learned in religious and secular subjects. He was a passionate and impressive orator, fluent in Russian, Yiddish, and Hebrew, and, above all, an effective activist for Jewish causes. He used the Rabbinate not only to perform administrative duties such as officiating weddings or interpreting laws, as his predecessors had done, but also as a platform to improve the general lot of Lithuania's Jews. Lobbying tsars and politicians on the one hand, he also aroused Vilna's faithful during powerful sermons delivered each Sabbath. A tall and stately man with a commanding presence, Rubinstein was a reassuring figure for Jews, non-Jews, and even the most anti-Semitic leaders.

Politics

Vilna served as the headquarters for many of the major Jewish political movements of the 19th and 20th centuries. With the beginnings of Socialism during the mid-19th century (the Communist Manifesto was written in 1848), a previously apolitical and disenfranchised Jewish community suddenly was thrust into debate and passionate dialogue over politics and Jewish survival. New political parties and movements appeared with amazing frequency and diversity. Among the first of the movements to get organized was labor, which got its symbolic start in 1871 when tobacco factory workers organized a strike against poor conditions. This served to catalyze the proletariat - both Jewish and Polish - and began a gradual process of unionization. Particularly strong was the Bund movement -(The General Jewish Workers Bund of Poland, Russia and Lithuania), which first convened in Vilna in 1897. Its platform was pro-Yiddish, pro-Jewish national autonomy, and opposed to Zionism. Bundists were resolved to fight it out and change conditions for the better for all in the Diaspora, through educating working-class Jews in self-defense and organizing, and struggling for practical improvements for for the whole community. Finally, Vilna was also one of the world's most important Zionist strongholds, with every major group of the movement represented: Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion), He-halutz (the Pioneer Movement), Betar (from the Revisionist Zionist movement), and Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair (the Young Marxist- Zionist Guard).

Printing and Press

Vilna was a major center of Hebrew printing and of the Jewish press, far out of proportion with its small size. It disseminated books and newspapers, ideas and scholarship to Jewish communities throughout Eastern Europe and across the world.

Hebrew printing was introduced in Vilna in 1799, and became a major industry before the middle of the 19th century. A number of small presses functioned over the course of the century, but the city's fame within the history of Hebrew printing stems from the enterprise run by the Romm family. The Romm company gained a nearmonopoly of Hebrew printing in Eastern Europe during the 1840s after other firms in the tsarist empire were closed by government censorship. The Romm Talmud, finely printed with a multitude of commentaries, completed in 1854, remains one of the greatest achievements in the history of Hebrew typography.

From the mid-19th century onward a Jewish periodical press sprouted as well, at first in Hebrew, most significantly Pirhe Tsafon, (1841), Ha-Karmel (1861), and Ha-Zeman (1905), an annual, a weekly, and a daily, respectively. Then, in the 20th century, Vilna also became a center of the Yiddish press. In 1929, five daily newspapers and one weekly, were publishing, including the widely read Vilner Tog. In the interwar period, Vilna was one of the three world centers of Yiddish publishing, along with Warsaw and New York. The publishing house founded in 1910 by B. Kletzkin issued the greatest works of modern Yiddish literature, including the classical writers and American Yiddish authors.

Secular Culture and Intellectual Life

Above all, Vilna was a community of intellectuals and ideas, a restless, cerebral dynamo in which many of the important Jewish movements of modern times grew and spread. During the 1890s, a clandestine Jewish theater was launched, hidden from the restrictive laws of the tsars, as members of the Bund offered modest performances of Yiddish plays. During 1903, the theater movement left longer the underground because Nokhem Lipowsky had received official permission to produce Yiddish plays. In 1908, the new Yidishe folks-teater was built. The Vilner Trupe, Vilna's first professional Yiddish theatre company, performed there during the hard times of World War I and went on to present some 91 plays by 1931. Secular artists and writers - of Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian - also flourished in Vilna's early 20th century avant garde world, which produced some of the greatest figures of modern Yiddish poetry and literature: Abraham Sutzkever (born in 1913 and now living in Israel), Chaim Grade (1910-1982), and Shmerke Kaczerginski (1908-1954), to name just a few among many. In 1929, a group of young poets and artists formed a small but esteemed society called Yung-vilne (Young Vilna), which became a fertile community of Jewish imagination until the war intervened.

Vilna once also housed some of the most important Jewish libraries in Eastern Europe: the Mefitse Haskalah library, the YIVO Institute library, and the Strashun library. The last was named for its founder, Matthias Strashun, a Talmudic scholar who was also a pillar among the city's Maskilim during the nineteenth century. YIVO, an acronym for Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut (Yiddish Scientific Institute), was created in 1925 East European Jewish intellectuals as a means of preserving Yiddish and East European Jewish history and culture. It became a unique institution in the Jewish world. YIVO's wide-ranging program of original research documented past and contemporary Jewish life, and elevated Yiddish culture to a level worthy of serious study. The Institute attracted Jewish scholars from around the world and was, according to historian David Fishman, "inundated" with a mass of historical, literary, artistic and ethnographic materials. The work of zamlers (popular collectors), who forwarded their materials to YIVO, "became the subject of poetic odes, short stories, and feuilletons; the stuff of folklore and legend."

As the Holocaust loomed and Vilna's Jews were confined to a ghetto, the tens of thousands of books in YIVO's collection were in danger of being lost. Before the Nazi annihilation of Vilna Jewry, several young Jewish scholars formed a now legendary "paper brigade" which organized the secret transfer of valuable books and documents out of the YIVO building, thus saving them from destruction. Many of these materials, together with some other surviving books and archives from the Strashun and YIVO libraries seized by the Nazis, were transferred after the war to the YIVO headquarters, which had been reestablished by Dr. Max Weinreich in New York in 1940. Now known as the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, YIVO is the only pre-Holocaust scholarly institution to successfully transfer its mission to the United States, preserving the intellectual and cultural legacy of Vilna Jewry. The largest repository of Yiddish and East European Jewish books, manuscripts, documents and artifacts, YIVO is today the world's foremost resource center for the study of East European Jewish history and culture; Yiddish language, literature, and folklore; and the American Jewish immigrant experience.

.avif)

.avif)